Bottom post of the previous page:

Sadly I know anything to do with Sky F1 in the UK, even the shortest Y/T video, is geo-blocked for us Southerners.RIP the Much Missed Murray Walker.

Bottom post of the previous page:

Sadly I know anything to do with Sky F1 in the UK, even the shortest Y/T video, is geo-blocked for us Southerners.

To honour the much missed Murray on a day that would have seen him opening a Telegram from the King on his 100th Birthday I saw this article /informal interview Motorsport Mag did with him a dozen years ago. I think many of us are aware of his father being a Motorcycle racer of note and also a commentator for the BBC. This led to opportunities for a young Murray to get work. I wasnt aware that in his first very low key job, knowing it was a one off opportunity he put on a performance far above what was asked! I knew he raced Motorcycles, but wasnt aware he raced in company of Surtees . It also covers in detail of the fights for the mic with James Hunt, and the difficulties of commentating from a studio far from the track.

https://www.motorsportmagazine.com/arch ... ay-walker/Lunch with... Murray Walker

For generations of fans, the knowledgeable and excitable Walker was the voice of F1. It’s 10 years since he hung up his microphone, but retirement is still the last thing on this octogenarian’s busy mind

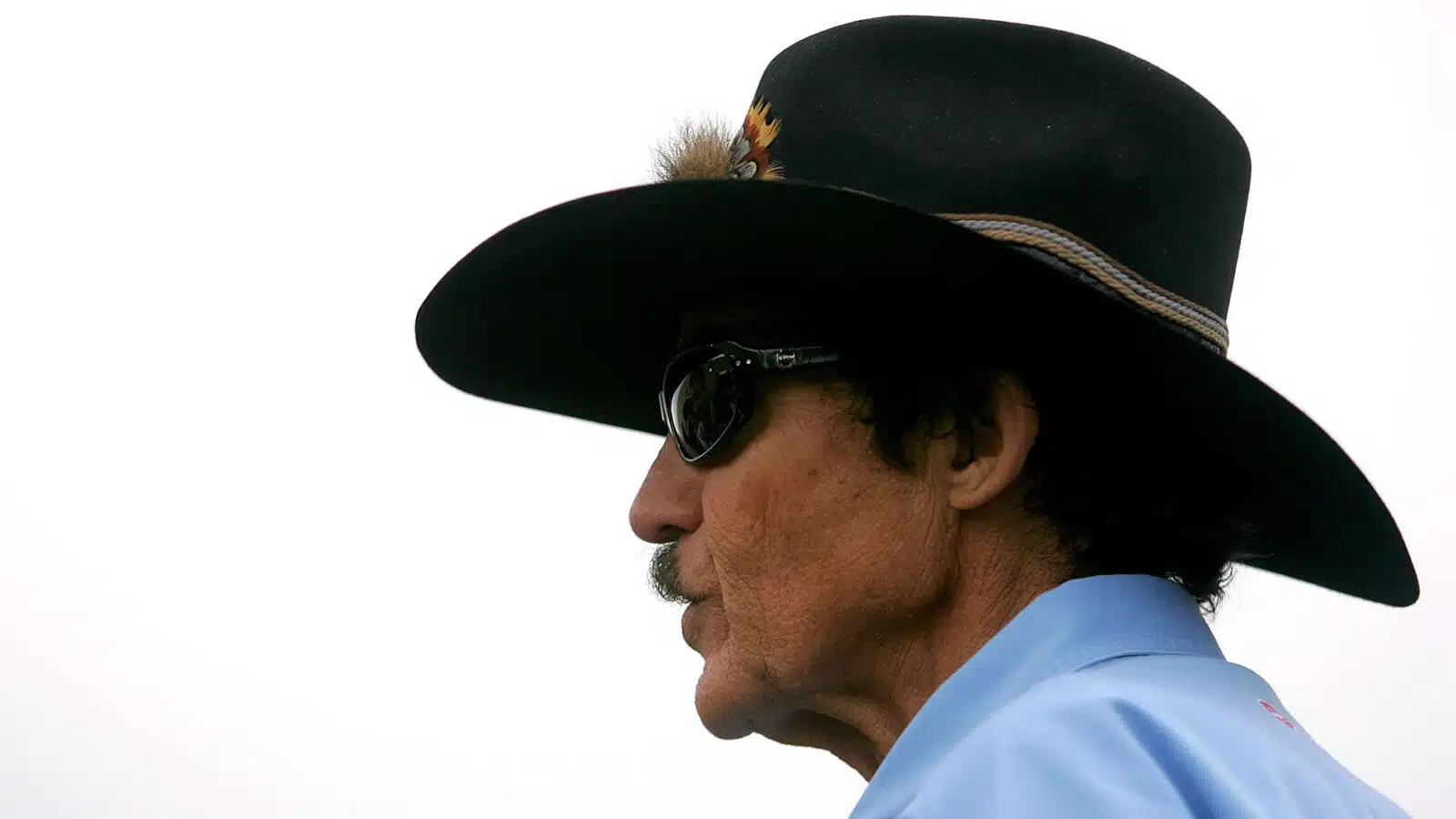

Murray Walker is a national treasure. For a quarter of a century his unmistakable voice brought Formula 1 into millions of homes: it could be said that he replaced roast beef and Yorkshire pud as the staple diet of the British Sunday afternoon. A vociferous minority may have objected to his strident, excitable style, memorably described by TV critic Clive James as talking like a man whose trousers were on fire. But there could never be any argument about his deep knowledge and love of the sport, his descriptive powers — or his unquenchable enthusiasm. As time went on, and F1’s TV audience grew exponentially through the Ecclestone era, he became the object of almost universal affection, not just among the public but within the F1 paddock as well. Murray’s voice became the very sound of F1: and when, a few weeks before his 78th birthday, he did his last commentary from the US GP at Indianapolis, everyone knew that F1 on the box would never be quite the same again.

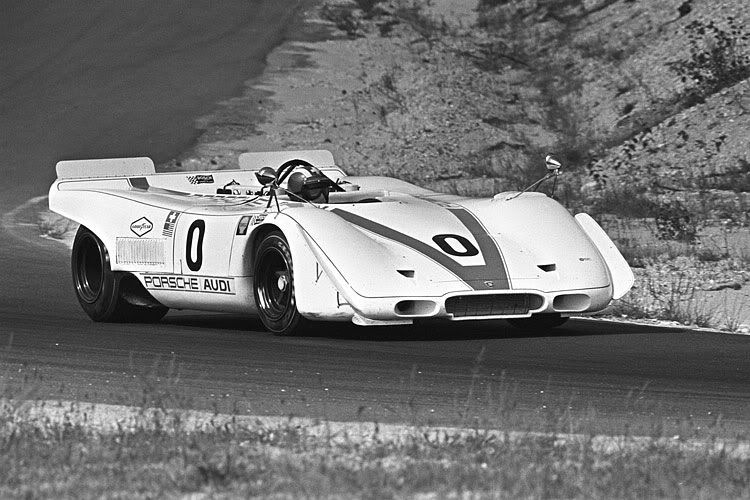

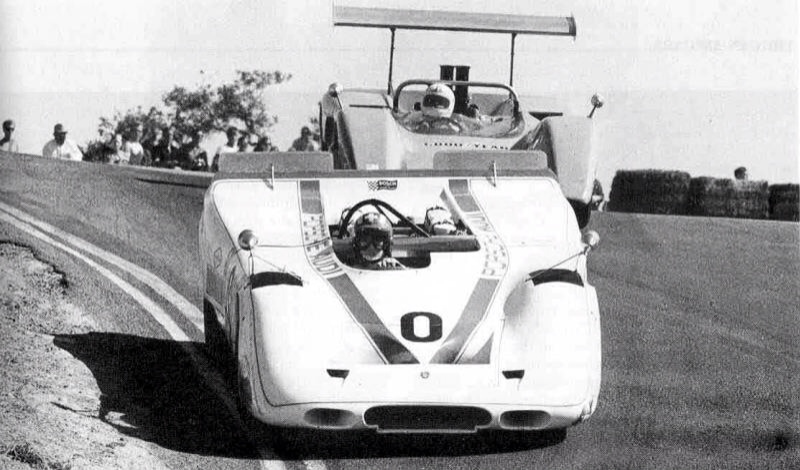

“I raced against John Surtees — well, I used to watch him disappear into the distance”

Murray covered Formula 1 from 1978 to 2001, but his microphone career actually spanned well over half a century. At first his speciality was motorcycle racing. Then he moved on to cover motor sport at every level, from touring cars to F3, truck racing to powerboats. He’s 87 now, a dapper, fit bundle of energy, fast-talking and endlessly goodhumoured, and he still hasn’t paused for breath: even now he’s pursued for public appearances, after-dinner speeches, cruise ships and the odd radio and TV gig. When we meet he is nonchalantly throwing off a bout of ‘flu to prepare for an 1800-mile railway trip from Darwin south across the Australian desert. He and his wife Elizabeth have lived for many years in a delightful modern house set in sylvan Hampshire countryside, with deer gambolling through the garden. The house overflows with books, pictures and mementoes of a life’s dedication to motor sport, a life in which just about every motor-racing great has been his friend. For lunch we repair to the Three Lions at Stockton, a fine restaurant on the edge of the New Forest.

Any radio or TV commentator will tell you that the single most important thing when you’re on air is not to put on an act. You cannot fake excitement, you cannot fake enthusiasm: broadcasting is a ruthlessly unforgiving medium, and any dishonesty, any artificiality, will be plain for all to hear. You can only be yourself. If your listeners like the person you are, you’ll hold their attention. If they don’t, you won’t. But you cannot pretend to be somebody you’re not.

Murray understands this, and so — love him or loathe him — Murray is Murray. I can confirm, having worked with him and been proud to call him a friend for over 30 years, that in the commentary box or out of it he doesn’t change. He talks in exactly the same way whether he is holding a microphone or a knife and fork. He is a wonderful raconteur, and his personal insights into the characters he likes or respects — and those he doesn’t — are vividly expressed. And his delivery is always the same. He enunciates every syllable with great clarity: commentary is pronounced ‘commentary’ rather than the more usual ‘comment-ry’. He loves adverbs. Rarely is an adjective allowed to stand alone without an adverb to increase its power. For Murray, a man is not just clever: he is enormously clever. A car is not just quick: it is gigantically quick. When something surprising happens he is not dumbstruck: he is literally dumbstruck. (Which is unlikely: whatever else Murray might be, he is never, ever struck dumb.) And, lest you should not be totally convinced of the force of what he has just told you, he will often add a favourite phrase: “…to put it mildly”.

The child is father of the man, and Murray’s happy childhood set him up for life. His father was a top motorcycle racer. Works rider for Rudge, Sunbeam and Norton, Graham Walker was European Champion, and dominated the 1928 Senior TT until his bike broke on the final lap. He won the first motorcycle Grand Prix at the Nürburgring, and in winning the Ulster GP became the first man to average over 80mph in a two-wheeled road race. “He was kind and brave, and I grew up admiring and respecting him, and wanting to be like him.” In 1935, having retired from racing, Graham began doing radio commentaries for the BBC, and edited the magazine Motor Cycling with great flair for 16 years.

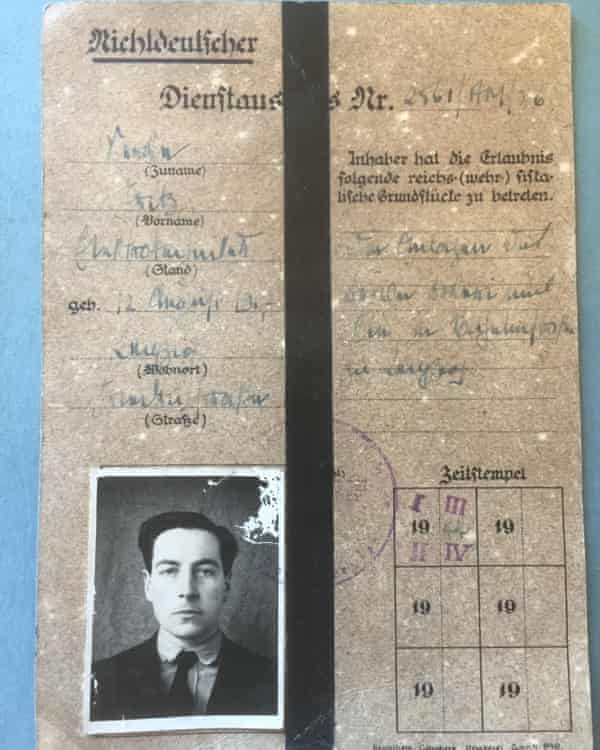

Sharing the talking with Barrie Gill

So Murray grew up in an atmosphere of motor sport. He first went to the Isle of Man TT races when he was two years old. In 1938 a family friend acted as interpreter for the Mercedes-Benz and Auto Union teams when they came to Donington, and Murray, a starstruck 15-year-old, was there to see Nuvolari’s Auto Union win, and to rub shoulders with Caracciola and Rosemeyer. Then came World War II. “War brought misery, pain, deprivation and tragedy, but — it’s a terrible thing to say — it also brought excitement. If you were a teenager there were three things you aspired to: fighter aircraft, submarines, and tanks. I wore spectacles, so Spitfires were out, and I didn’t fancy being under water. So I volunteered for tanks.” He was part of the invasion crossing the Rhine in March 1945, and ended up with the rank of Captain. “It’s a cliche, but ‘in as a boy and out as a man’ was certainly true in my case.” When peace came he got a job with the Dunlop Rubber Company, and found himself working in its advertising department.

“My phone rang. ‘You busy on Saturday, Murray? I want you to cover Weightlifting’”

“I started racing bikes, probably because I thought my father would want me to, rather than because I passionately wanted to. I raced against the young John Surtees — well, I used to watch him disappear into the distance, and saw him again when he lapped me — and the pinnacle of my achievement was winning a 250cc heat on the old anti-clockwise grass track at Brands. I realised racing wasn’t for me, so I switched to trials, and did rather better. On my 500T Norton I won a gold in the International Six Days’ Trial, and I won a first-class award in the Scottish Six Days.” Then in September 1948 something happened to change Murray’s life.

“My father was due to do radio commentary from a combined bikes and cars meeting at Shelsley Walsh, but at the last moment he had a clashing engagement. So the public address commentator, a man called Charlie Markham, was asked to do the BBC broadcast. When the event organisers asked my father if he had any suggestions for a PA replacement, he said, “Well, you could give the boy a go.” Now with PA you tell the spectators what they are going to be watching, and then you let them watch it. Not me. I subjected them to a non-stop barrage of commentary, knowing the BBC people were there and could hear me.

“It must have worked, because at the Easter Monday Goodwood meeting in 1949 I was given a BBC audition. My trial was recorded onto a disc via a huge contraption in the back of a Humber Super Snipe, to which my microphone was connected by a length of wire, so I couldn’t stray any further than my wire allowed. And four weeks later I found myself doing my first live radio broadcast — from the British Grand Prix at Silverstone, positioned out at Stowe. The main commentator was Max Robertson, who was the BBC’s tennis commentator. He knew as much about motor racing as I knew about fly-fishing — and, moreover, he actively disliked it. Using the circuit layout where they charged up the main runways towards each other, the race was won by Baron de Graffenried’s 4CLT Maserati from Bob Gerard’s ERA and Louis Rosier’s Talbot. Towards the end of the race, which lasted nearly four hours, John Bolster’s ERA suddenly came cartwheeling down the track towards my box and deposited its driver in an inert heap just in front of me. I thought, ‘Blimey, they didn’t tell me what to say about something like this.’ So in a masterpiece of understatement I just said, ‘Bolster’s gone off!’ He survived, but he never raced again.

With father Graham in 1932

“Then I got sent to the Isle of Man, and that was the start of a 14-year commentary partnership with my father for TT week. I found myself the BBC’s motorcycle man on races, scrambles and trials, and I also did the public address at just about every circuit in the land, learning my craft. It was only bikes then: car racing became the preserve of the urbane and enormously competent Raymond Baxter, with support from Robin Richards when they needed a second voice.

“My first TV broadcast also came in 1949. It was a motorcycle hillclimb, just a sort of filler really, and the young Peter Dimmock was the producer. The camera was the size of a large wheelbarrow, and it was all pretty primitive. Then ITV pioneered motocross, and I did that. It became very popular. In the dreadful winter of 1962 the whole country was snowed in, all sport was stopped, and somebody at the BBC decided, ‘We’d better do one of those motorcycle scrambling things.’ Dave Bickers was the sport’s big hero then, and at the start of this BBC event he stalled, and got away a lap after everybody else. He stormed through the field, and by the start of the final lap he was closing on the leader. The BBC producer in London shouted down the line, ‘This is bloody marvellous. Get them to do another couple of laps.’”

“James Hunt? I was literally gobsmacked. What the hell did he know about broadcasting?”

Meanwhile Murray’s business career blossomed. From Dunlop he went to Aspro, and then joined the agency world at McCann Erickson. In 1959 he moved to Masius Wynne-Williams, where he remained for 23 years. His stories of his life in advertising — on accounts like Mars, Vauxhall, Babycham, Embassy cigarettes, Weetabix, Wilkinson Sword — are manifold and hilarious. But somehow his prodigious energy allowed him to combine a hectic working week with ever more commentary work. Murray is a man who never likes to say no to anything.

“One Thursday, sitting at my desk at Masius, my phone rang. It was the top man at BBC Sport, Paul Fox — now Sir Paul — whom everybody feared like God. ‘You doing anything on Saturday, Murray?’ Saturday was my wedding anniversary. ‘No, Paul.”Right, I want you to go to Bristol and cover the Commonwealth Weightlifting Championships. Don’t say you know nothing about weightlifting, because neither does anyone else.’ I went through the phone book, found something called the British Weightlifting Association, phoned them up and asked to speak to the top man. They put me on to one Oscar State, who turned out to be the Max Mosley of weightlifting. I offered him a lift to Bristol — ‘provided you talk to me about weightlifting.’ He said, ‘I never talk about anything else.’ I went home, got Elizabeth to find me a broom handle, and spent the evening practising the Press, the Snatch and the Jerk. Mr State filled up my brain on the way to Bristol, and the programme went fine.

“But fundamentally I was the chap who did all the motorcycle stuff. I had the great privilege of living through and talking about a golden era of bikes: British machines like Norton, Velocette, AJS, men like Geoff Duke, John Surtees, Mike Hailwood, Barry Sheene. Mike became a close friend. His father was the millionaire owner of a string of motorcycle dealerships, ruthless and determined, and Stan poured money into Mike’s racing. He got Ducati to make special bikes for him, he hired top tuner Bill Lacey exclusively to work on his engines, and Mike always had the best. But it wouldn’t have been any use if he hadn’t had the ability, and he had the ability to genius level. He was also a wonderful man, totally laid-back, the ultimate party animal.

“Barry Sheene was a lovable cockney rogue, but also extremely bright: spoke fluent Spanish, spoke Japanese, an extremely good self-taught engineer. Everybody liked Barry, and Barry liked everybody. In live interviews he’d say the most outrageous things and get away with it, when anybody else would have given grave offence.

Murray Walker and James Hunt shared a microphone for 13 years

“Put a microphone in front of John Surtees in his two-wheel days, and he’d answer any question with one word. You’d go blundering on, trying desperately to get more than a monosyllabic response. Now with John you put a penny in the slot and it never runs out. He’s a forceful, opinionated character, but his opinions are always very much worth listening to. He has principles, and he sticks to them through thick and thin — which is why he walked away from Ferrari in 1966.

“As the BBC gradually covered more four-wheeled stuff I did it: F3, touring cars, Formula Ford, truck racing, anything with an engine. Except Formula 1. What little they did of that remained Raymond Baxter’s preserve. Then at the end of 1976 James Hunt won the World Championship, and suddenly Britain was waking up to Formula 1. So for 1978 BBC TV decided to do a Sunday evening programme called Grand Prix — half an hour of highlights from that afternoon’s race, taking the pictures off Eurovision. By then Raymond Baxter had a major commitment to Tomorrow’s World, so they asked me to do the commentary. That’s where it all really began. I would go out to each Grand Prix on the Thursday — only the European ones, because the budget didn’t run to the long-haul races — mooch about, talk to people, watch Saturday qualifying and then fly back to London on Saturday night. On Sunday afternoon I’d watch the Eurovision feed at Television Centre, they’d edit it down to a tight 27 minutes and I’d dub the commentary on afterwards. Sometimes the edit was only finished at the last minute, so I’d have to commentate as the programme went out, doing it all as though I was there. You’d jump from lap five to lap 23, and vital chunks had to be left out. It was extremely demanding.

After the 1979 Monaco GP James Hunt got out of his Wolf and walked away from his career as a racing driver. And our producer, Jonathan Martin, had this revolutionary brainwave. He called me in and said, ‘Two commentators in future, Murray. You’ll be one, the other will be James Hunt.’

“James Hunt? I was literally gobsmacked. To put it mildly. What the hell did James Hunt know about broadcasting? He was a racing driver! And one I didn’t much like. I was old enough to be his father, and we were out of two different moulds. To me he was a rude, arrogant Hooray Henry who drank like a fish, smoked like a chimney, and womanised like there was no yesterday, let alone tomorrow. Plus, all commentators are insecure, it’s the nature of the business. I thought: it’s the thin end of the wedge. They’re pushing him in and pushing me out. So, due to a combination of insecurity and actual dislike, I wasn’t best pleased.

“The first Grand Prix we did live from the circuit was Monaco 1980. There were no commentary boxes then: just two folding chairs out on the pavement behind the Armco and a flickering little TV monitor. car-pieces in, cars lined up, no sign of James. With two minutes to go he shambles up, barefoot, jagged jeans shorts, dirty T-shirt, half-drunk, bottle of rose in his hand. Slumps into the chair and takes a swig from the bottle. And God, his feet smelt.

“But the amazing thing is, the broadcast went all right. Because, of course, James was a brilliant choice. He was famous, he was a World Champion, he had the knowledge and he had the eloquence. Our styles couldn’t have been more different, which was maybe why it did work. I’d be bouncing around on the balls of my feet, a metaphorical bucket under each foot to collect the adrenaline that was literally pouring off me, to put it mildly, and James would be slumped in a sullen heap beside me, bottle at his side. It’s well known that Jonathan Martin made us share a microphone so we didn’t talk over one another. Very sensible with two egotistical people in the box, each of whom knew that what he wanted to say was infinitely more interesting and important than anything the other bloke had to say. I’d reluctantly pass the microphone to James and, while he was still talking about how many pounds per square inch there were in the tyres, I’d be trying to wrestle it back from him because something faaantastic had just happened. I must have been very hard to put up with.

Interviewing Nigel Mansell after his 1992 championship win… with his mic switched on…

“I don’t think there is such a thing as a dull motor race, but if things did need livening up a bit I only had to say something complimentary about Riccardo Patrese. At once James would gesture for the microphone and pour out invective and bile on poor Patrese, whom he always held responsible for Ronnie Peterson’s fatal accident at Monza in 1978. He wasn’t short of an opinion on anything: one year we were commentating on the South African Grand Prix from TV Centre, watching the off-air pictures, although of course we were careful to give the impression that we were at Kyalami without actually saying so. Suddenly, mid-race, James starts banging on about the evils of apartheid, about which he had very violent views. Mark Wilkin, the producer, put a piece of paper under his nose on which he’d scrawled: ‘Talk about the race.’ Anyway,’ said James, ‘thank God we’re not there.’

“His trademark was always to turn up at the last possible minute, but at Spa in 1988 he didn’t turn up at all. Come the warm-up lap, where the hell is James? The race starts, where the bloody hell is James? We put out a story that he was back in the hotel, in bed with food poisoning. In fact he was back in the hotel, in bed with a couple of Belgian nurses. Allegedly.

“I worked with James for 13 years, and it’s a tribute to both of us that we stuck it out. I don’t want you to think I hated James, because you couldn’t hate him. There was a lovely man inside, and when he fell on hard times the nice bloke took over. We were never best mates, but we did grow to like and respect each other. That’s why it was so dreadfully sad when the heart attack took him, aged only 45. Not long before he died, I remember sitting down to dinner with him at Imola, and I asked what he’d like to drink. ‘Orange juice, thanks, Murray.’ ‘Orange juice? What happened to the wine?’ And he said, ‘I think I’ve had my share now.’

I’ve worked with a lot of co commentators: Graham Hill, Barry Sheene, Jonathan Palmer. Working with Martin Brundle was a different kettle of fish. Martin is the best bloke I ever worked with. He’s driven for eight F1 teams, been on the podium, won Le Mans, been World Sports Car Champion. He knows what he’s talking about, knows just how to say it, and he’s got a great sense of humour. With him I never had any problem. It was him that had a problem with me. I shudder now, looking back, because when the race started I was so obsessed with what was going on that Martin used to say, ‘I could have walked out of the commentary box and Murray wouldn’t have noticed.’

“Conditions for broadcasters have improved beyond all recognition and, like virtually everything else in F1, that’s Bernie’s doing. Yes, he’s doing it for very good financial reasons, but when I look at tapes of our early days, the pictures and coverage are just archaic. Now you’ve got all the telemetry the teams have got, fantastic graphics, pitlane reporters, an hour’s preview before the race, summaries afterwards. Unbelievable when you think how far we’ve come, and it’s all down to Bernie.

Murray disliked Senna’s on-track ruthlessness, but had a soft spot for Mansell

“Any contact I’ve had with Bernie has always been extremely friendly. Of course he’s a hard man, probably a ruthless man, but I’ve never had any business dealings with him. The last thing I’d like to have to do is negotiate with Bernie. I’d walk into the room fully clothed and walk out naked. But from a historical perspective, I put him and Enzo Ferrari in the same bracket at the top of motor sport, and if I had to choose between them I’d plump for Bernie, because he has made the sport what it is today. In 2001 he said, ‘You’re not really stopping, are you?’ I told him I was, and he said, ‘You’ve got a good 10 years left in you — and I want ’em.’ He proposed I join his FOM TV operation. But I had to tell him, politely, that I didn’t want to do it.

“I did interview Enzo Ferrari: an incredible personality. I was taken into his office and he was sitting there, wearing his dark glasses, with the portrait of his dead son Dino on the wall and, on the desk, the black glass Prancing Horse that Paul Newman had given him. I knew I had to say something to make him take me seriously, so I said, ‘Mr Ferrari, you don’t know me, but you knew my father.’ Not many people realise that Ferrari had a motorcycle team in the 1930s, using Rudge Whitworth bikes, when my dad was sales and competition director there. That broke the ice. I won’t pretend it was the greatest interview I’d ever done — we spoke through an interpreter — but he answered all my questions with immense authority. You knew you were in the presence of a great man. He said that, of all the drivers who’d driven for him, Peter Collins was his favourite. And he said he always regretted that Stirling Moss never drove for Ferrari in F1 — which he was going to do, in a blue-painted Rob Walker 156 in 1962, but of course the Easter Monday Goodwood crash put paid to all that.

“Fangio I saw race many times in the 1950s, but I didn’t meet him until much later. I had this image of a shy, uncommunicative bloke with a squeaky voice who spoke no English, so I was worried about how our interview would go. I couldn’t have been more wrong. He was a very nice man with no side, no boastfulness, perfectly straightforward. We talked about his early days racing in South America, and of course we talked about the 1957 German Grand Prix. He had total recall — what line he took on every corner, what revs he was pulling in each gear, precisely where he was able to make up ground on Hawthorn and Collins, how he passed them. He said, ‘It took me two weeks to recover from the stress and effort of that race. I had never driven like that before, and I never did again.’

“People are always asking me who was the greatest, and there’s no answer to that, because there’s no yardstick to no to compare Fangio with Senna, or Clark with Schumacher. My subjective hero is Tazio Nuvolari. His record with bikes and cars is incredible. And such a charismatic personality. That man had charisma literally oozing out of the roots of his hair.

“I don’t think Ayrton Senna is the greatest racing driver of all time. I’d known him since Formula Ford and F3, when he had those great battles with Martin Brundle. He was the most intense and deep-thinking man I ever met. In an interview you’d ask a question, and he’d sit for about half a minute, and you’d think, ‘Have I lost him? Is he on another planet?’ and then he’d come out with a carefully-thought answer that covered every aspect of the question you’d asked. But I could not respect him for the ruthlessness with which he drove. I know they’re in it to win, and the man that finishes second is, to quote Ron Dennis, the first of the losers. But I think Senna took it too far — like with Prost in Japan in 1990, for example. He was the instigator of a way of driving that has become the norm in F1 today: get to the front at all costs and stay there. Schumacher is the same. It’s easy for me to say. I’ve never raced a car in my life. But I think it’s ethically wrong.

“I started on F1 the year Mario Andretti became World Champion for Lotus, and he was a lovely man, a wonderful communicator with some fantastic one-liners. Eddie Irvine I never got on with, simply because he was unpredictable. You never knew whether he was going to be courteous or bloody rude. Keke Rosberg was a great personality. He collared me in Australia before his final GP, Adelaide 1986, and said: ‘Murray, this is my last race, and I really want to win it. So if I’m doing well, for Christ’s sake don’t say anything about it and jinx me.’ Well, he took the lead, so I had to describe it — and near the end he went out with a puncture.

Murray rates Damon Hill as a better driver than Graham

“Damon Hill and Graham Hill couldn’t have been more different. Graham was a hard worker, a great storyteller, life and soul of the party, drop his trousers at the drop of a hat. Damon was equally hard-grafting throughout his career, but could be introverted and withdrawn. But, subjectively, a better driver, and a nicer bloke. Damon has done so much for the BRDC since he retired. As president he could easily have been just an ineffective figurehead, but he’s turned out to be a great leader, and now we’ve got the British Grand Prix guaranteed for the next 17 years.

“Ken Tyrrell was one of the most outstanding people it’s ever been my privilege to meet. People like Ken don’t exist in F1 any more, and never will again. How he beat Ferrari, beat the world, working out of a woodyard in Ockham is beyond me. Because I was with the BBC he seemed to regard me as the fount of all knowledge about worldwide sport, and particularly cricket, about which I know literally nothing. I’d be walking across the paddock and this great stentorian bellow would ring out, ‘What’s the score, Murray?’ I’d say in bewilderment, ‘What score ?”The West Indies, you pillock.’

“The dividing line between honest genius and dishonest genius is very narrow. Colin Chapman was right on that line most of the time, and occasionally he crossed it. But he was the most inspired innovator of all time. Adrian Newey can’t do what Colin Chapman used to do because he’s so circumscribed by today’s rules. Derek Gardner’s six-wheel Tyrrell, Gordon Murray’s fan car — we won’t see their like again. When the TV audience saw a car with six wheels they knew it was different. Explaining the F-duct to them isn’t so easy.

“I’ve got a soft spot for Nigel Mansell, as many people know. He’s not everybody’s cup of tea, but when you look at where he started and where he finished, it’s an incredible achievement. There was a lot of whingeing along the way, and Nigel always tended to make a mountain out of a molehill. But, as I found when I stayed with him and his family at his homes in Florida and the Isle of Man, he’s a good old boy at heart.

“I had the classic nightmare with him once in Brazil. In the pitlane, 40 degrees, he gave me a 20-minute interview, a very good one, and then back in the van the engineer found he’d forgotten to turn the mic on. I had to go back to Nigel — and you know what a prickly bugger he could be — and ask him to do it again. He very decently did so, but every time I interviewed him after that he’d say [here Murray slips into a passable imitation of Mansell’s Birmingham tones]: ‘Have you turned on the microphone, Murray?’

“You have to say that Nigel certainly wasn’t a grey man. Something I regret about modern F1 is that all the drivers, as you perceive them in public anyway, are grey men. Because of the constant spotlight under which they have to work, the lack of association with their peers in other teams, their obligations to the sponsors, you never get to see them as human beings. You wonder if characters like Innes Ireland or Mike Hawthorn could exist today. I interviewed Michael Schumacher countless times, and he was always a helpful, friendly, cheery bloke. But charismatic he is not.

Schumacher struggles to get the joke at Murray’s send-off at Indy in 2001

At my last race, the US GP in 2001, after qualifying I was ushered along to the Williams pit and there were Bernie, several of the team bosses and just about all the drivers. It was a wonderful surprise and a heart-warming occasion. Amid much hilarity Tony Jardine, who was running the proceedings, gave each driver a card which they had to read out, with various mistakes I was supposed to have made. When it came to be Michael’s turn his card said: ‘Here comes Michael Schumacher, son of Ralf Schumacher.’ Of course I’d never, ever said something so daft. Michael looked at the card and said, ‘What is this? I don’t understand. Ralf is my brother, not my father.’ Afterwards he said to me, ‘The meeting this afternoon, it was in your honour ?”Yes, Michael, it was,’ I replied. ‘But they were making fun of you. Is that your English sense of humour ?”Yes, Michael, I suppose it is.’ He looked at me and said, ‘Oh. Oh, I see.’ But plainly he didn’t.

“We have to talk about my so-called bloopers, because everybody always does. While I bravely laugh and say I don’t care, I would far rather go down in posterity as someone who entertainingly knew what he was talking about, than a bumbling idiot who continually opened his mouth and put his foot in it. But the truth is that very few of the ‘mistakes’ people accused me of were factual errors — because I worked extremely hard to get my facts right. They were slips of the tongue, inversions of words, malapropisms, or simply my way of saying things. ‘The car in front is absolutely unique except for the car behind, which is identical’, or ‘Tambay’s hopes, which were previously nil, are now absolutely zero.’ When you take statements like those out of context they make no sense at all. But I know what I meant.” And, once the British public got used to Murray’s way, for most it was a source of entertainment rather than annoyance.

“But at the German Grand Prix in 2000 I did make an appalling factual mistake. Schumacher’s Ferrari went off at the first corner, but in my mind he couldn’t have made a fool of himself in his home Grand Prix, and I made a great song and dance about how it was Barrichello. Next day the Daily Mail published a bitterly critical piece about my incompetence and my ability to get things constantly wrong, and said it was time the old fool was parked. I was hurt, of course, but I also sadly wondered if they were right. I’d been commentating for over 50 years, and I was tired. I talked to Brian Barwick, the top man at ITV Sport and, next to Mark Wilkin, the man I’d most enjoyed working with. He said he felt no need for me to go, but that if I was thinking of retiring he wanted me to do one more season, to wind down. So that’s what I did in 2001. At my last British Grand Prix the reception was unbelievable. There were lots of affectionate farewell banners in the crowd, and the RAF parachute team even jumped out of the sky with a banner about me.”

The 2001 season over, Murray produced a best-selling autobiography, Unless I’m Very Much Mistaken, and continued to be busy with after-dinner speeches, corporate presentations, magazine columns and occasional radio and TV work. And now, at 87, he shows no sign of stopping. “My idea of purgatory is to give up working. I don’t want to work flat out, but the thought of not being busy is death.

“I always regarded it as my brief not just to inform but to entertain. F1 is very complex, and it was my job to try to pull all the different strands together in an entertaining way. And I knew that 95 per cent of my audience weren’t interested in the diameter of the gudgeon pin. What they wanted was to share the excitement that I was lucky enough to be witnessing. And lucky is the word: my work has taken me round the world umpteen times to countries I would never otherwise have visited, and I have rubbed shoulders with some outstanding people. I have been incredibly, gigantically lucky.”

This season the BBC’s F1 coverage moves on again. Brundle steps into the lead commentator’s shoes, and David Coulthard joins him in the box. It’s a whole new angle, and promises to provide brilliant coverage. But there will never again be a commentator quite like Murray. For the generations of British fans who have followed on television the sport they love, Murray Walker will always be a gigantically memorable part of Formula 1. To put it mildly.

https://www.motorsportmagazine.com/arch ... silver-foxPiero Taruffi: The incredibly versatile Silver Fox racer

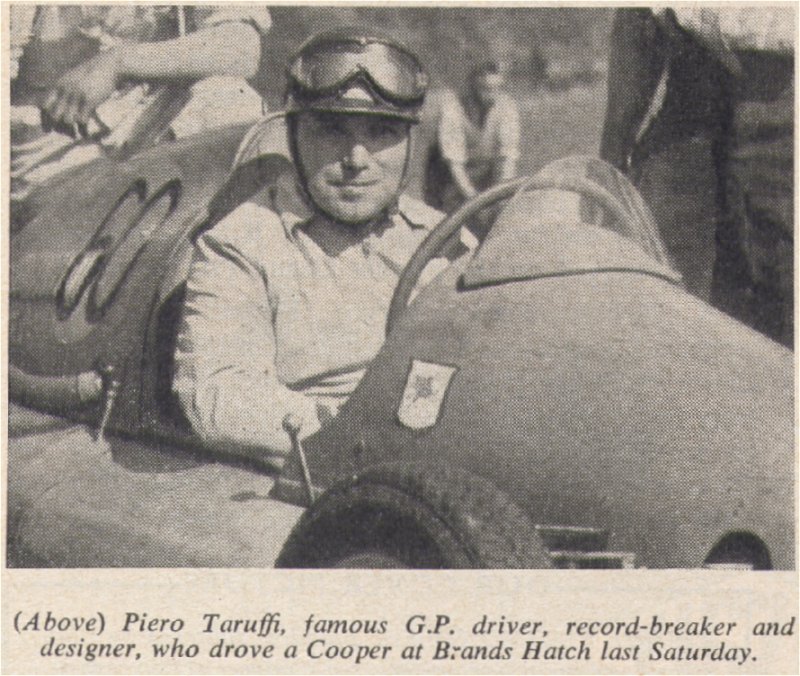

Taruffi: one of motor sport's most diverse racers

Like many schoolboys in post-War Britain, I had an insatiable appetite for stories about a character called Wilson. He’d swim the Channel before breakfast, score a pre-lunch century against the Australians, then win Olympic gold medal for the mile in the afternoon. Piero Taruffi was no comic-book superman, but his record for versatility stands supreme and his story easily be mistaken for a work of fiction.

The surgeon’s son had more than his fair share of strength, stamina, dedication, and determination. From 1923-57 he competed in 206 events, in cars and on bikes, scoring 66 wins plus 44 seconds or thirds. The sport’s supreme all-rounder was good enough to win a world championship grand prix as well as the Targa Florio, Mille Miglia and Carrera PanAmericana. No one can match that record. And in his career he raced Fiat, Alfa Romeo, Bugatti, Itala, Maserati, ERA, Delage, Cisitalia, Lancia, Ferrari, Cooper, Thinwall Special, Oldsmobile, Mercedes, Ford, Vanwall and Chevrolets as well as AJS, Guzzi, P&M, Norton, OPRA, Rondine and Gilera bikes.

And that’s not all… In 1937 he became the fastest man on two wheels and would go on to claim 53 international bike records. Another 37 fell to cars he designed himself. And during the early ’50s he combined his racing with running the Gllera team whose star, Geoff Duke, was virtually invincible. On the morning of 27 May, 1951, he masterminded Gilera’s effort at the Swiss GP, then boarded his Ferrari, battled through torrential rain and finished second only to Fangio. In younger days he was a racing oarsman, played tennis, wrestled, represented Italian universities in international ski contests and came fourth in 1933’s French slalom championship.

Piero Taruffi 1953 Carrera Panamericana

At ’53 Carrera Panamericana – he would finish second

I met him in 1976, when the fuel crisis prompted Mobil France to organise a high-profile economy driving contest. Taruffi and I were in the multinational Fiat team. He stooped a little, his legs never quite recovered from an almighty accident in 1934, but the silver-white hair, swept back from the broad, bronzed forehead, was as thick and glossy as ever. Muscles rippled in arms and shoulders that had tamed big, brutal cars in such races as the Targa Florio, with 602 corners to every 45-mile lap.

A lesser man might have treated the event as a free holiday, but the flame still burned. He told me that he would check-out the 200-mile route on the day before the event and science may never create a machine clever enough to measure how little time it took me to say “Yes” when asked if I would to join him. That drive was an education, as well as a privilege, because the maestro’s diligence recalled Enzo Ferrari’s comment about the meticulousness that made his name a by-word. Pin-sharp navigation was essential, because we would be driving solo, so he made careful notes about landmarks and sections where time might be lost and clawed back. That evening we skipped dinner to discuss tactics after transferring all the information to map and roadbook. He won his class, of course, and deserved most of the credit for me finishing second in mine.

Taruffi was born in Rome in 1906. Seventeen years later, he won the Rome-Viterbo time trial in the family’s Fiat 501S tourer. It was a modest start, but in 1928, he bought a Norton, won eight of the nine races he entered and became Italy’s 500cc champion. Beating demi-gods like Tazio Nuvolari and Achille Varzi gave him as much satisfaction as anything he achieved in later life. Taruffi was soon offered a drive by Ferrari, then head of Alfa’s competition department, but switched to a Type 59 Bugatti for the 1935 German GP. At about 125mph a universal joint failed, twisting the back axle and locking the brakes. The Bugatti flew over a hedge, he escaped with a bruises and trudged back to the pits.

“My Nurburg’ accident made me think, I must admit. But enthusiasm gave me strength and I determined to press on. In racing one must never show one is scared, or draw back when things first go wrong. You just shrug it off and have another go,” Taruffi wrote in his autobiography, Works Driver.

In 1946 he became manager, consultant, chief tester and number one driver for Casitalia whose single-seaters were based on Fiat 1100s. They were good times, but in 1951 he joined Ferrari and finished third in the following year’s championship, behind team-mates Ascari and Farina. Later that year he and Luigi Chinetti shared the Ferrari 212 Inter that won the Carrera PanAmericana, storming over 10,000-feet-high passes, averaging almost 90mph for nearly 2000 miles. This made Taruffi a legend in Mexico. He was dubbed El Zorro Plateaclo The Silver Fox and taxi drivers pinned his photograph in their cabs, alongside the F Virgin of Guadalupe. He was then 45, but 1952 was his busiest season and his 16 races included a victory in the Swiss GP. He also masterminded Gilera’s capture of the world titles for riders and manufacturers. When I met Geoff Duke, 40 years later, he had nothing but praise for the shrewd, cool, deep-thinking Italian.

Two finishes from ten starts tell the story of 1953 with Lancia’s 2.9-litre V6 sports-racers. Finishing second in the Carrera Panamericana should have been the highlight – notes taken during a characteristically thorough recce enabled him to drive through fog at a 120mph but it turned to ashes when his team-mate, Felice Bonetto, was killed. Lancia got it right the next year when our man won the Targa Florio and Circuit of Sicily, which he regarded as an even tougher race. He won the Giro di Sicilia again in 1955, this time in a Ferrari, and also had two drives for Mercedes, finishing fourth in the British GP and second, hard on Fangio’s heels, at Monza. No wonder his Technique GiMotor Racing is one of the best books ever written on the subject.

The Silver Fox promised his wife Isabella that he would retire when he won the Mille Miglia. Taruffi’s record went back to 1930, but victory had proved as elusive as dreams so often are. Isabella regarded the promise as her indomitable husband’s way of saying he would never call it a day.

Taruffi leads von Trips across the line in a formation finish at ’57 Mille Miglia

In 1957 he was offered a Ferrari 315S with 370bhp to send it bellowing down the straights at to 175mph. He knew every inch of the course but went over it again before the race, memorising any feature that could help bring victory. Others carried a co-driver armed with pacenotes none more famous than this magazine’s Denis Jenkinson but the Silver Fox was also the lone wolf whose rivals included hard-charging youngsters such as Stirling Moss, Peter Collins and Wolfgang von Trips. There were problems. Well before Rome, the halfway mark, the transmission started making ugly noises, forcing Taruffi to use the higher gears as much as possible. Rain near Bologna demanded a ballet dancer’s touch on the throttle, because the Ferrari could spin its wheels at 125mph in top. But after ten hours 27 minutes and 47 seconds he crossed the line first, three minutes ahead of von Trips. The real Mille Miglia was never run again, because the swashbuckling Marquis de Portago had crashed, killing himself, his co-driver and several spectators.

Taruffi thanked Ferrari for the use of the car, pocketed his share of the prize money — “Less than I won this weekend,” he told me in 1976 — and retired after 34 years of racing and breaking records.

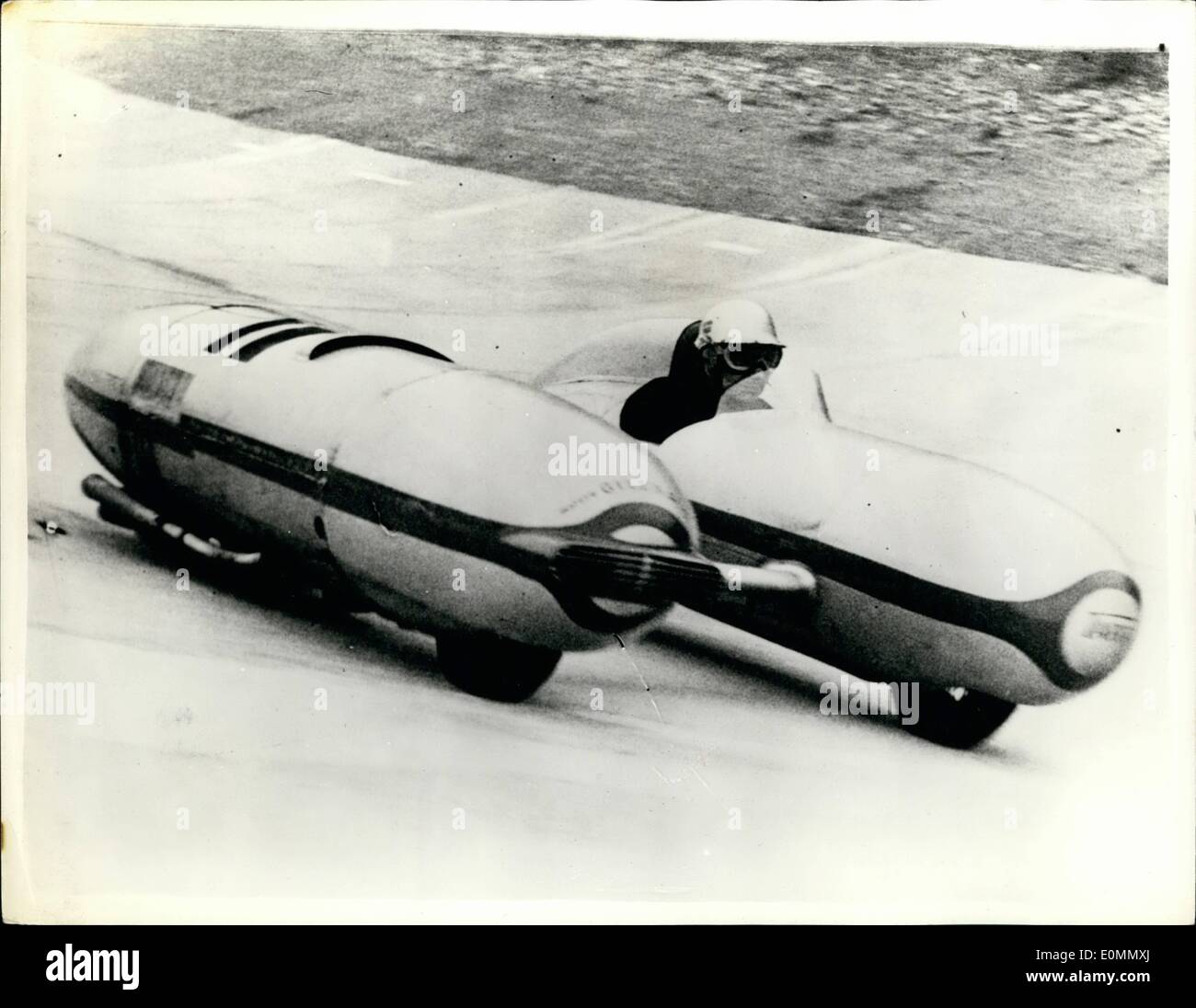

He had become involved in the quest for speed after taking a job as assistant to Carlo Gianini, the chief engineer of a company dedicated to building motor bikes and experimental aircraft. Together they designed the four-cylinder, 500cc Rondine. Carefully streamlined and ridden by Taruffi, it took the world’s flying mile and kilometre records at over 150mph in 1935. Two years later, hunching those broad shoulders into the aerodynamic bubble of a supercharged Gilera 500, he bagged 34 more records, including the flying mile at 169.05mph and the hour at 127mph, which remained unbroken until 1953.

After the war he applied his aerodynamic knowledge to cars, and in 1948 built the first Tarf — the name was derived from his own which looked like a pair of wheeled torpedoes joined by wing-like central spars. A variety of car and bike engines were used and the Tarf’s triumphs induded becoming the first vehicle ever to cover 200 kilometres in an hour with a 500cc power unit. At the other end of the scale, a Maserati engine with a twostage supercharger punched the same car to almost 200mph.

We talked far into the night. He had raced against most of the legendary heroes, and beaten many of them at least once. Who was the greatest? A difficult question, he mused, if only because it was difficult to compare drivers from different eras. But the first he mentioned was Bernd Rosemeyer, the ex-biker who tamed the fire-breathing Auto Unions in the ’30s, followed by Nuvolari and Varzi. Ascari, Fangio and Moss were outstanding among those with whom he duelled towards the end of his career.

He recalled that blood-curdling incident at the ‘Ring in 1935 — we had, coincidentally, met one of the Bugatti team’s mechanics earlier in the day — but added, with wry smile, that it had not been his worst accident. In 1934 he entered the Tripoli Grand Prix in a Maserati whose supercharged 4.5-litre V16 cranked out 350bhp. Tripoli was a superfast circuit, and the Maserati was good for 165mph, but on the fifth lap the brakes suddenly locked solid in a nightmare of smoke and melting rubber. Taruffi was hurled from the wreck, breaking his left arm and smashing a leg so badly there was talk of amputation. He spent three months in hospital, tended by his father who kept the promise he had made at the start of Piero’s career; “If you ever come to grief, I’m always here to sew you together again.”

Italian racing driver Piero Taruffi driving his 'Double Torpedo' car, designer by Maserati, as part of a world record attempt, Terracina, Italy, April 5th 1952.

Taruffi engineered cars for land speed records as well as competing in grands prix – seen here at Terracina in 1952 in his ‘Tarf’

The great man chuckled as he finished the story; “When I went off the track I hit a big sign advertising beer. While I was in hospital I had a letter from the beer company, hoping I was making a good recovery.., and enclosing a bill for the damage to the sign! When I went back to Tripoli, the next year, the scene of the accident had been renamed Taruffi Corner. I was very flattered, but that is not the best way to become famous.”

We met for the last time in 1987, when more great drivers than a strong man could shake a stick at in a month of Sundays gathered at the Imola circuit to celebrate one of Ferrari’s many anniversaries. Blue eyes still twinkled beneath the silver hair, and the smile was as warm as ever, but Old Father Time was approaching with his remorseless, pitiless scythe. When the Silver Fox died in 1988, I recalled Mark Anthony’s tribute to Brutus; “This was the noblest Roman of them all.”

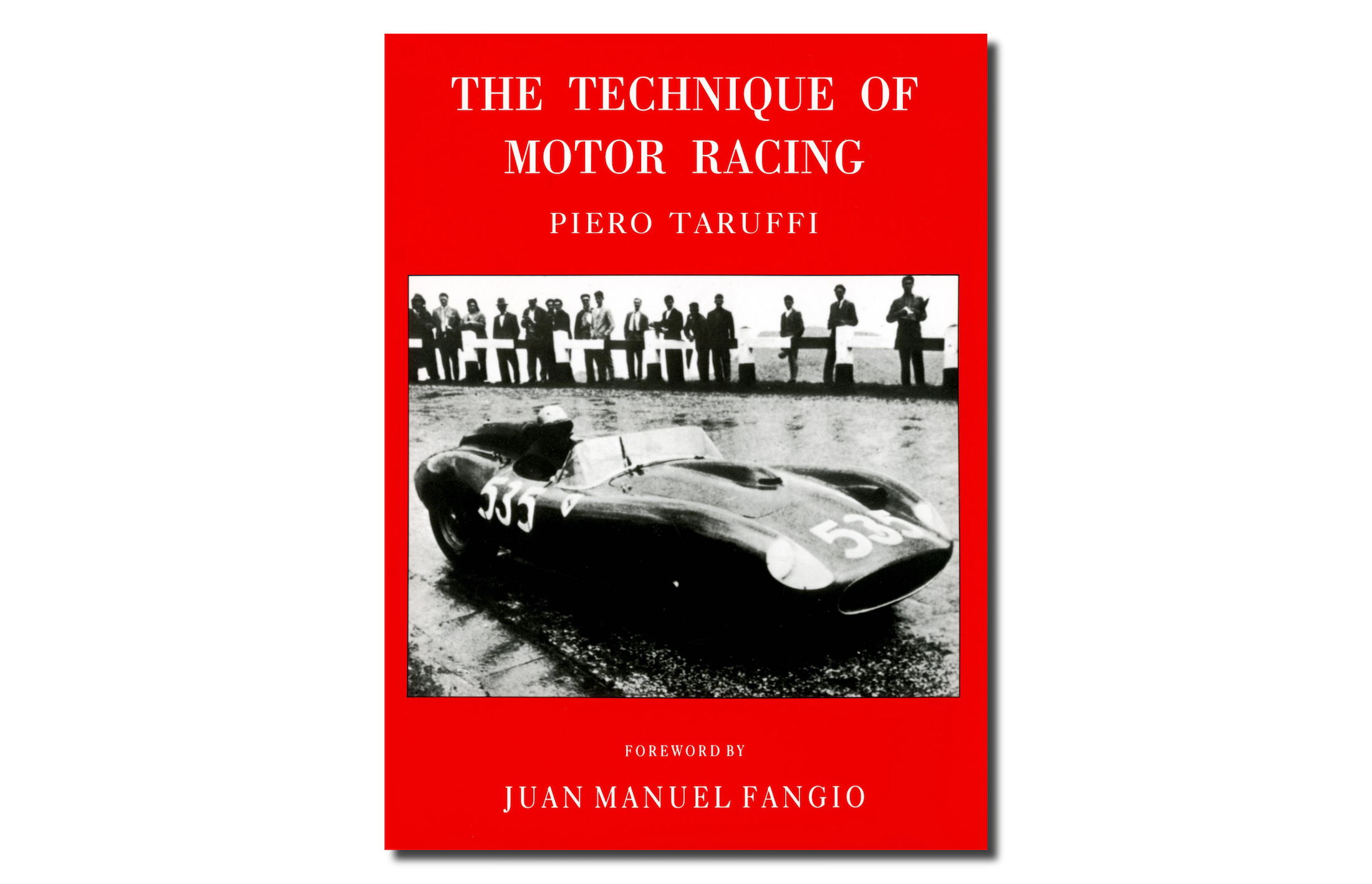

The Technique of Motor Racing by Piero Taruffi is the book that all other instructional motor racing books are measured against.

It was written by Taruffi, nicknamed the “Silver Fox”, in 1959 after he retired from motor racing in 1957

What set him apart from many of his contemporaries was the fact that he was a trained engineer, he applied his engineering knowledge to his racing, designing many vehicles himself including successful land speed record breakers and race cars.

It was this formal engineering training coupled with his natural driving ability that set Taruffi apart, and made him the perfect person to write “The Technique of Motor Racing” a book that became the bible for all serious racing drivers for decades to come.

The book is 125 pages long and it includes a wealth of information that will improve any driver, including optimal driving positions, cornering techniques, limit of adhesion, how to drive on banked corners, general advice for racing drivers, pre-race preparation and techniques and maps of the major circuits of the era including: Zanvoort, Sebring, Nurburgring, Monza, Imola, and Monaco.

https://www.motorsportmagazine.com/arch ... tony-rolt/Looking back with Tony Rolt: Jaguar Le Mans hero who plotted Colditz escape

Born a motor sport enthusiast, Tony Rolt's racing career spanned from a promising youngster to a engineering pioneer — and everything in between

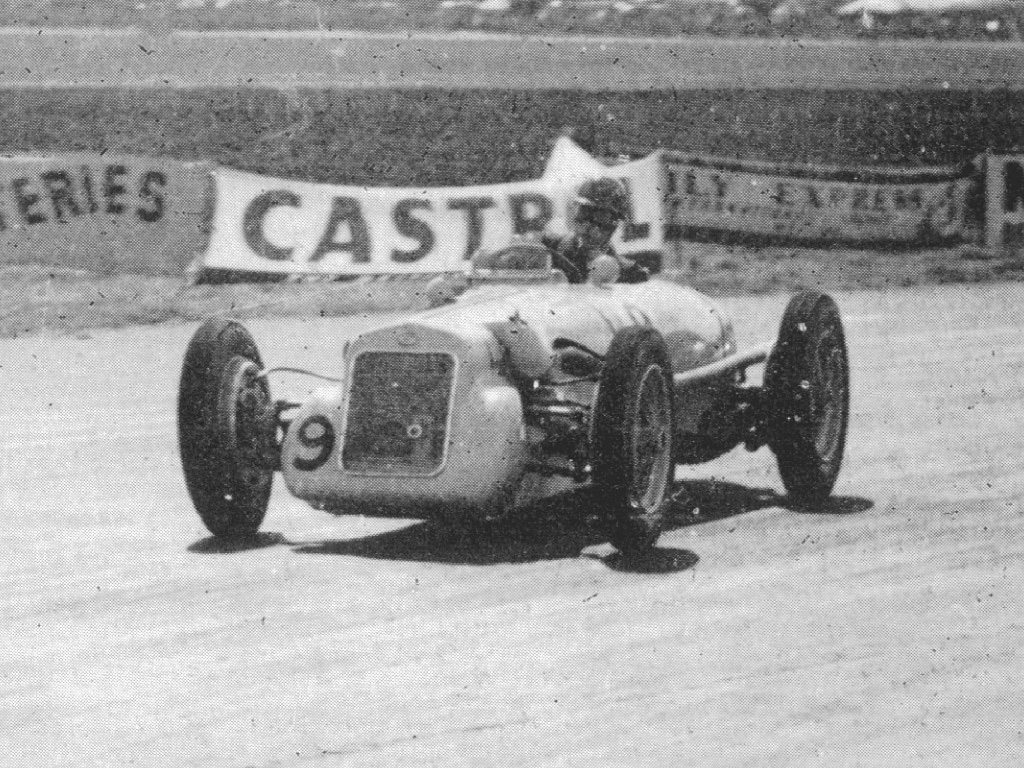

It seems hard to believe that Tony Rolt could be old enough to have raced at Donington, but the fact remains that, at the relatively tender age of twenty-one he won the 1939 British Empire Trophy at the wheel of the ex-Bira 1.1/2-litre E.R.A. “Remus”. Since that period when many hailed him as a promising youngster, a varied racing career brought him the first Le Mans victory to be gained at an average speed of over 200mph as well as a regular place in the Jaguar works team.

Perhaps, more than anything, his name is connected most strongly with the research work into four-wheel-drive systems and their application to racing and road cars with Ferguson Research Ltd. Now Managing Director of FF Developments, an entity in its own right which has been in existence for just two years, we visited Major Rolt at his Coventry premises in the shadow of the big Massey-Ferguson plant to chat informally about his racing memories and his work with Fred Dixon and Harry Ferguson.

A.P.R Rolt was born shortly before the end of the First World War, firing an early enthusiasm for matters mechanical long before he was ever old enough to hold a driving licence. His family lived for a time on a farm in North Wales and the young Rolt bounced around the farm tracks “in an old Singer and an early G.N.”, demonstrating sufficient enthusiasm for motoring as was necessary to swing his parents round to providing him with a Morgan three-wheeler before he left for Eton. One was permitted to drive three-wheelers at the age of 16, so this willing workhorse was immediately put to work in trials; “it wasn’t particularly suitable with that two-wheel-front, one-wheel rear arrangement. But that’s all there was, so I made do.” He confesses that, as a young boy, he often spent hours sitting by the roadside near Maidenhead watching for an interesting car to appear.

These schoolboy watches by the roadside were often sustained in the company of Lance Macklin, a face he was later to meet regularly on the circuits of Europe once the war was over. When the writer, later quizzing Major Rolt on the subject of D-type Jaguars, remarked that these cars were his personal favourites when he was growing up, our subject agreed with the theory that one forms one’s basic criteria by which one judges everything later in life when one is young and impressionable. So, although Major Rolt has a particular soft spot for the D-type — “remember, it was only a 3.4-litre engine… I think Duncan (Hamilton) managed to wind one up to almost 190mph at Agadir or somewhere like that” — his personal favourites were the 2.8-litre Roesch Talbots. “These were the cars I really loved. As far as I was concerned, Bentleys were just tanks, Bugattis too finicky. Those Talbots always won the team prize. You can’t imagine how I envy Anthony Blight, owning those team cars of his!”

Tony Rolt D-Type

The Jaguar D-Type would be a career-favourite of Rolt’s — but he kept a soft spot for his beloved Talbots

The days of car-watching were soon over and Rolt’s ambitions to go motor racing remained unfulfilled. His first “real” motor car was a 1936 Triumph Southern Cross: “Ex-Donald Healey, overhead inlet, side exhaust, straight six. Do you know, it would do over 110mph when you wound it right up.” The Triumph was duly dispatched to Spa for the 24-hour sports car race shortly alter Rolt’s seventeenth birthday where he achieved a worthy fourth place in the 2-litre class. “First, second and third were a team of German Adlers; that was real Teutonic efficiency for you. But I’d actually competed in the same race as Dick Seaman, he was driving a Lagonda which gave me a great thrill to say the least.” Unfortunately, a slight disagreement with the local constabulary in rural Wales as to the precise speed achieved on one occasion with his later, and rather rare, Triumph Dolomite was responsible for his reduced programme in 1937, even though the RAC were not obliged to suspend competition licences automatically!

By this time Tony Rolt had moved to the Royal Military College at Sandhurst, duly passing out and being commissioned into the Rifle Brigade before World War II broke out. But, before that unfortunate turn of events, Rolt had purchased “Remus” from Bira for the 1938 season and embarked on a very ambitious programme of racing. It was during the winter of 1938/39, when searching for more speed and road-holding from the E.R.A., that he met the rugged and rough former motorcyclist Fred. W. Dixon who had already built up a substantial reputation for preparing and driving Rileys.

Dixon agreed to carry out the preparation of Rolt’s E.R.A. while also mentioning the fact that he’d prepared plans for a four-wheel-drive record-breaking car. Rolt took a great interest in this project, but managed to persuade Dixon that his ideas would be better if they were applied to circuit racing rather than record breaking. By this stage, very little development had been done in the sphere of four-wheel drive. Back in 1903, Spyker had built such a car which, powered by an 8.6-litre engine, had won a Birmingham Motor Club hillclimb. In 1932, Ettore Bugatti built his hillclimbing pair of four-wheel drive Type-53s and Rene Dreyfus had actually established a new record for the La Turbie hillclimb near Nice, being the first competitor ever to ascend the 6-kilometre course at more than 100kph.

Bugatti Type-53

The Bugatti Type-53

It was eventually agreed that Dixon would prepare a four-wheel-drive chassis powered by Rolt’s E.R.A. engine, but although plans were drawn up for this project in 1939, the onset of war meant that they had to be shelved. Nevertheless, the two men formed a small company called Dixon-Rolt Ltd with the intention of examining such systems and Rolt spent a lot of time attempting to persuade the war office that they would be ideal for military vehicles. However, they were not particularly interested and the matter was left in abeyance after Rolt was captured at Dunkirk and Dixon just got on with his work for the war department on other matters.

After the war, Rolt returned from his enforced sojourn in the notorious Colditz, where his most famous exploit had been to instigate the building of a glider for an escape attempt from the Castle roof, to find Dixon still hard at work in his small Reigate factory and he retired from the army in 1948 to resume a career in motor racing “despite my parents urging me to take a choice between the army or racing, emphatically pointing out that motor racing could not be made to pay. Of course, I was absolutely determined to prove otherwise.” Rolt’s first post-war mount was the famous Alfa Romeo Bimotore, the twin-engine record breaker in which Nuvolari had bravely established some 200mph-plus times on an Italian autostrada in 1935. However, this car was now minus its rear engine, owing to an overwhelming inclination to eat up its rear tyres at the rate of one set every ten miles or so.

In addition to his efforts with the Alfa Romeo, in which he took a fine second place at Zandvoort, Rolt got together with two friends, Geoff St. John Horsfall and Pat Fergusson (no relation to Harry Ferguson) and, together with Dixon, built up their first four-wheel-drive test bed, this being a rather stark two-seater equipped with a pre-war Riley engine. This showed considerable promise.

Meanwhile Harry Ferguson, in whose Belfast garage Fred Dixon used to keep his Rileys whilst competing in the pre-war Ards T.T. races, was making a big name for himself in the tractor world, while also distinguishing himself by being one of the few people to sue the Ford Motor Company with success (this, being in connection with tractor design) and obtained some three million pounds in damages. He had kept in touch with Dixon and, approving of the four-wheel-drive concept, offered a small amount of monetary assistance to the precariously financed Dixon-Rolt Ltd. Shortly afterwards, Aston Martin designer Claude Hill, the man who designed both engine and chassis of the DB1, left David Brown’s firm and joined Dixon-Rolt Ltd. He was later to design the famous Ferguson Project 99.

Rolt’s racing career, meanwhile, was developing apace. Between 1949 and 1952 he drove all manner of cars, notably Rob Walker’s famous Delage and Delahaye which Walker had promised his wife he would never again race in circuit competition after the war. In 1950 and 1951, sharing the wheel of a Nash-Healey on both occasions with Duncan Hamilton, Rolt finished fourth and sixth at Le Mans. His attraction to long-distance racing was the factor which had driven him to Spa when he was just seventeen.

Trouble for the Jaguar of Tony Rolt and Duncan Hamilton Le Mans 1952

In 1952 came the most significant move of his racing career; he was invited to join the Jaguar team, “I’d proved quite competitive at Dundrod where I actually lapped the C-type faster than Stirling. Then they asked me who I’d like as my co-driver and I said Duncan. They said ‘Duncan, you must be mad!’ But he joined me in the team for 1952 and we always drove in long distance races together.” The first Le Mans was a disaster for Rolt. “Stirling had been blown off by the Mercedes on the Mille Miglia and came back telling us that there would be no way of keeping up, so Jaguar rushed through the construction of a more streamlined ‘droop snout’ nose section. Ironically, the Mercedes were not as quick at we’d feared, but all the Jaguars overheated and were sitting in the pits, three cars retired, by the time it was seven o’clock on Saturday evening.”

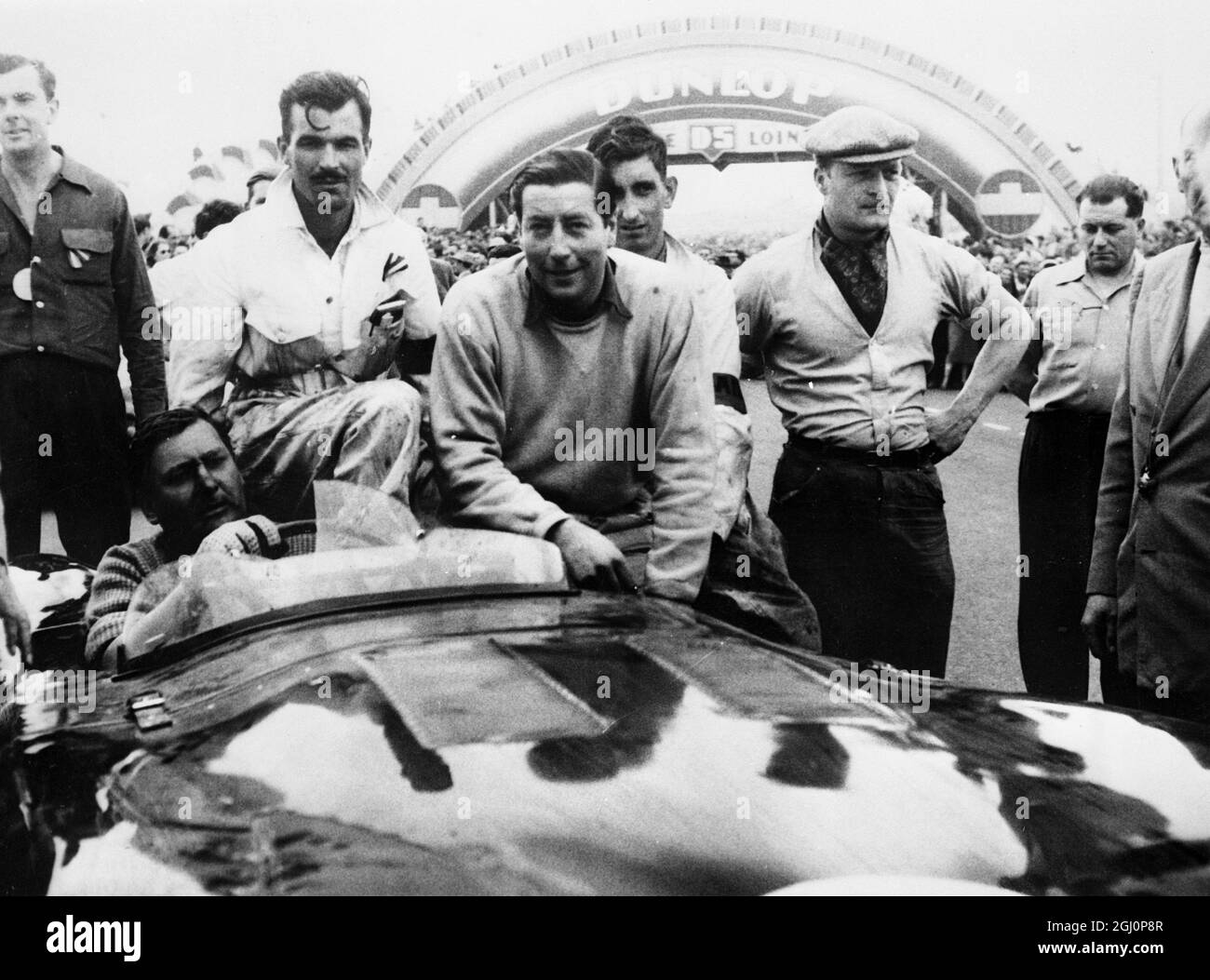

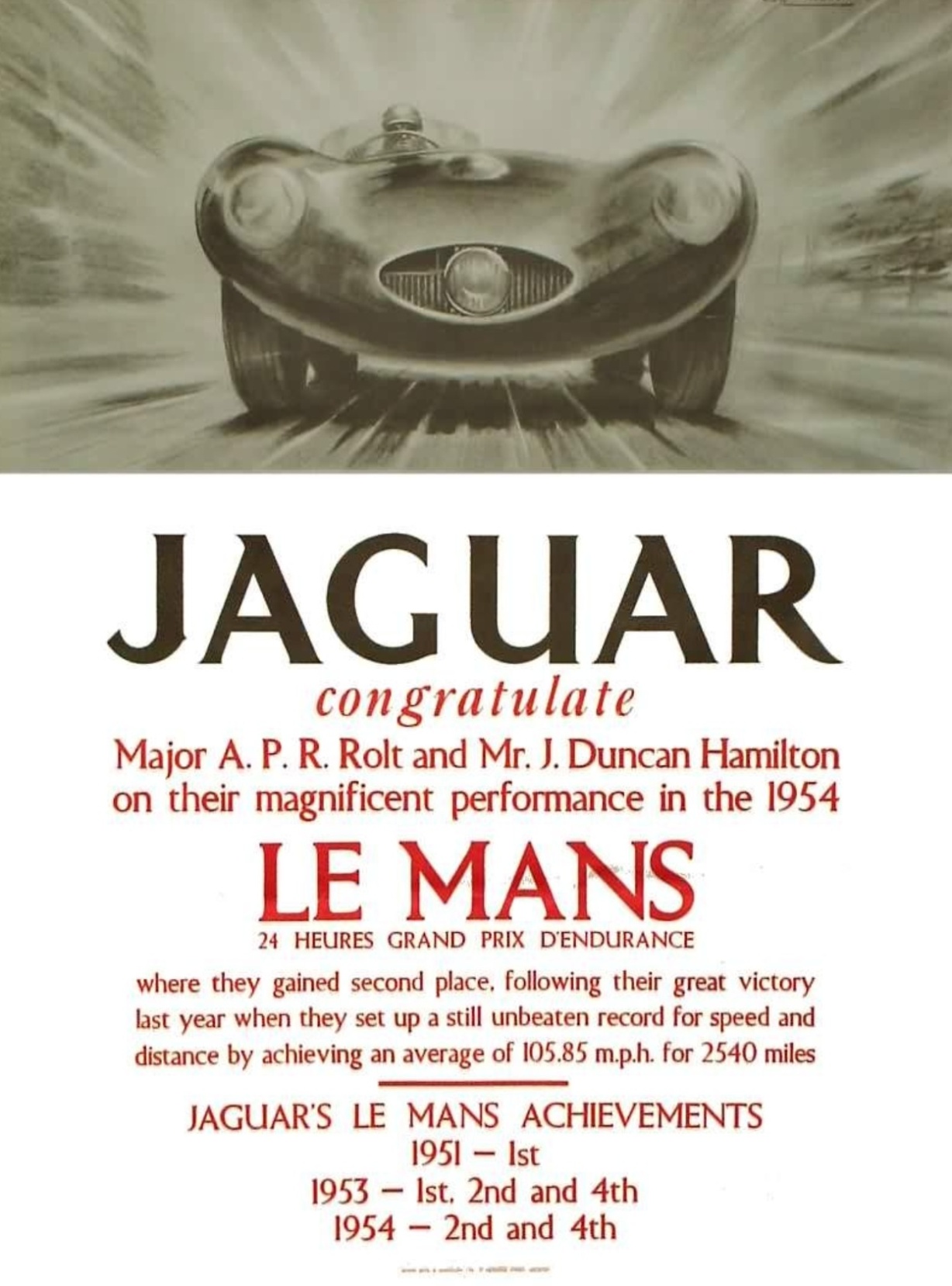

The 1953 race was memorable, because Rolt and Hamilton became the first to win the 24-hour classic at an average speed in excess of 100mph at the wheel of a 3.4-litre C-type. However, Rolt’s memories seem more stirred by the 1954 race, where their D-type ran to second place on its very first outing.

On the billiard-smooth surface of Le Mans, this classic aerodynamic machine could reach 170mph which, in retrospect, seems shattering for twenty years ago. “We had a lot of problems in practice, and we were told that we’d only got time for two laps. But I told Lofty England that I had to do one flying lap, which meant I’d really got to put in three laps. As I came past the pits to start my flying lap I turned a blind eye to the ‘come in’ boards and tried as hard as I could all the way round. The chequered flag was out when I arrived back at the pits, but I tore across the line and then obliged Lofty to have a lengthy argument with the organisers to establish whether I’d got the time or not. They eventually agreed to give us 4 min. 23 sec. which was really not bad for my first flying lap in a D-type!”

Rolt and Hamilton had a troubled time in the early stages of the race, their D-type starting to misfire from an early stage. They stopped at the pits to change plugs and check the electrics, it eventually becoming clear that the Jaguar team was using their car as a “guinea pig” to find out what was wrong so that if any of the other team cars ran into trouble they could be quickly repaired. Eventually it was diagnosed as dirt in the gauze of the fuel filters, so they went back into the race with a vengeance.

“We agreed to drive flat out all the way,” recalls Rolt. “We were chasing the Gonzales/Trintignant Ferrari all night and the following day. We could take ten or fifteen seconds a lap off it when Trintignant was at the wheel, but we were pushed to take two or three seconds a lap when Gonzales was driving.” Nevertheless, the Jaguar roared on through the night at a terrific pace, hauling in the Ferrari all the time.

Tony Rolt in Jaguar D-type with broken headlight at 1954 Le Mans 24H

Flat-out pace earned Rolt and Hamilton second place at Le Mans in 1954

Then came an incident which slightly clouded the race for Tony Rolt. “It started to rain, in fact hail, like I’ve never seen before. The road was awash on the Mulsanne straight and smaller cars were skating everywhere. I realised that I couldn’t see properly, so I stopped at the pits to ask for a vizor. It wouldn’t have taken a few seconds, but the Ferrari was in its pit at the time and they just waved me out again. Next time round it was still very bad, so I came in again. My goggles were full of water. I hopped out to fix on a vizor and the next thing I knew was that Duncan had jumped into the car and was away. That caused just a little bit of tension, I really don’t know why they couldn’t have given me that vizor.”

Having made up a four-lap deficit, the Rolt/Hamilton D-type finished second, less than four kilometres behind the winning Ferrari. Rolt’s success over the years with Jaguar enabled him to continue with Rob Walker’s team, handling the 2-litre Connaught and later the 2½-litre Formula 1 Connaught, but he was always in touch with the motor industry as, back in 1950, Harry Ferguson had bought out Dixon-Rolt Ltd and installed them, now as Harry Ferguson Research, near the tractor plant in Coventry. This quite naturally suited Rolt, for Jaguar’s factory was just a few miles away from the Ferguson premises.

By the end of 1956, although still a member of the Jaguar works team, Rolt fully realised that an increasing commitment to Harry Ferguson Research Ltd was going to take more and more of his time, so he retired from active motor racing at the end of the following year to devote his full time efforts to the development programme. Later, much later, he tried Stirling Moss’s Rob Walker Lotus 18 during a test session and concluded that he retired at about the correct time. “I liked to see the nose of the car, I liked something to aim with, and after a few laps I came in and told Rob that I just couldn’t get used to it.”

Of course, whilst trying to sell the British motor industry the concept of four-wheel-drive on a commercial basis, Ferguson Research laid plans at the end of the 1950s for their famous Project 99 Grand Prix test bed. Claude Hill’s work on this distinctive “centre engined” machine with its rear-mounted driving position was completed by early 1961, but only Tony Rolt remained of the original triumvirate to see this project through to fruition.

Jack Fairman 1961

Jack Fairman in a 4-wheel-drive Ferguson P99 in the 1961 British Grand Prix

Fred Dixon had died five years earlier after splitting with Ferguson in 1952 after a difference of opinion and poor Ferguson himself died suddenly in the autumn of 1960. The decision was taken to proceed with the project and, although Rolt was more than capable of driving the car fast enough for test purposes, Jack Fairman was called in to drive it in the British Empire Trophy and the British Grand Prix at Aintree, proving without doubt that four-wheel-drive allied to the Dunlop Maxaret braking system was substantially superior in the wet. The P99 was run under the Rob Walker banner and, after Stirling Moss won the Gold Cup at Oulton Park in the car, Ferguson offered the whole project to any team that was interested.

Unfortunately, grand prix racing didn’t aspire to any great heights as far as engineering standards were concerned in the early 196os and there wasn’t a British team with the technical ‘know-how’ to successfully adopt the P99. Despite a later trip to the Tasman Series and success in Peter Westbury‘s hands in the RAC Hillclimb Championship, the car wasn’t used very much again.

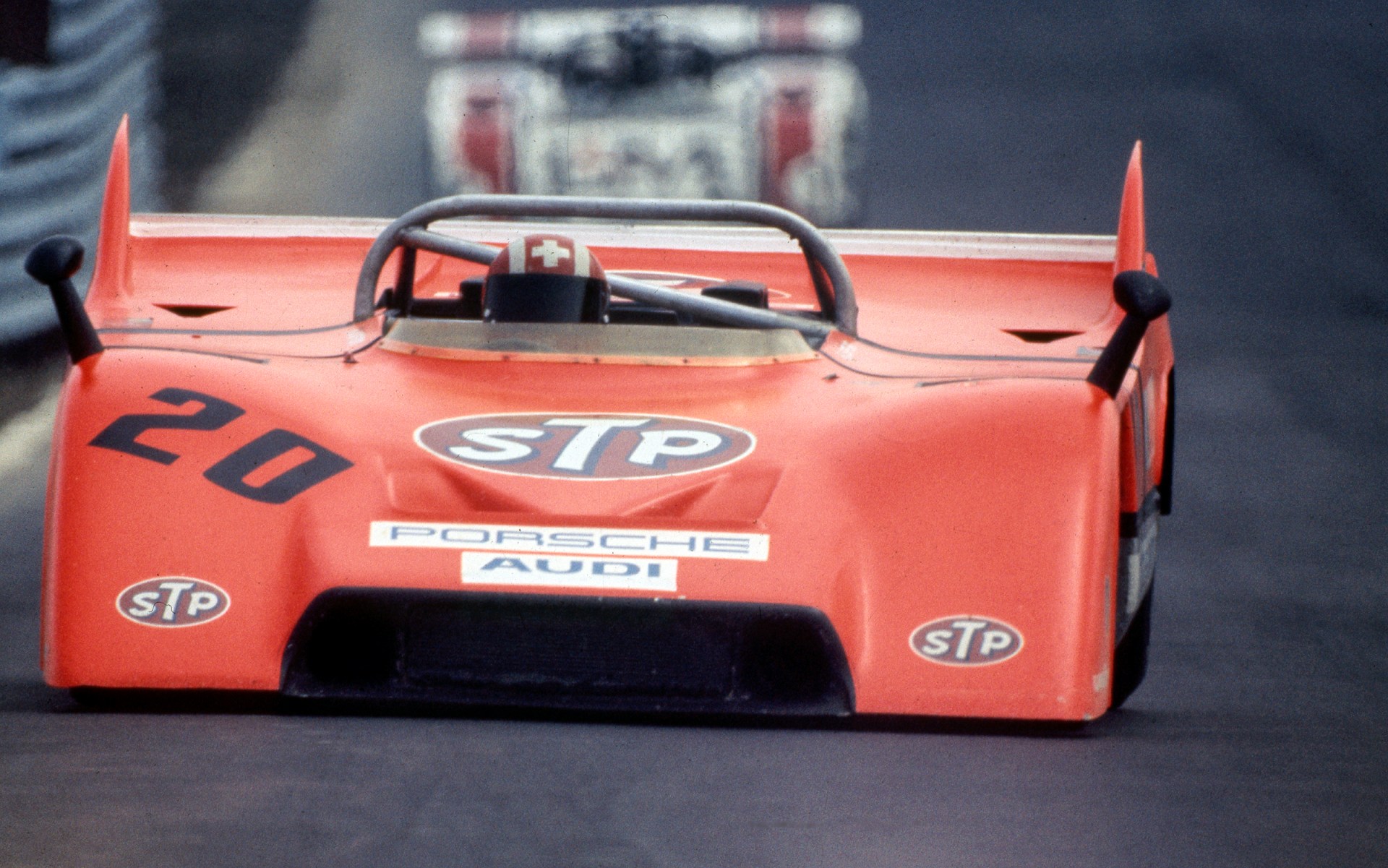

Meanwhile, Ferguson Research Ltd built up several systems for racing cars as well as trying to interest the British industry as a whole. Rolt made contact with Andy Granatclli, a move which sparked off a series of four-wheel-drive systems for the Novi-Fergusons, the STP Turbine car and latterly the Lotus 56 turbines. “BRM wanted to do a system for the H16,” Roll recalls “but they were not prepared to turn the engine through 180 degrees and they wanted to use the same gearbox. It really wasn’t feasible. Incidentally, you realise that there was a hole down the centre of the H16 motor between the cylinder banks that was to accommodate the drive for a four-wheel-drive system.” As it was, BRM had sufficient problems with the car to forget four-wheel-drive and it wasn’t until 1969 that the constructors ended up swinging their engines through 180 degrees and taking the power on the “front end”.

Harry Ferguson Research Ltd has now changed its name to FF Developments and it is GKN who hold the licence to mass produce the Ferguson four-wheel-drive system should a bulk order be required from any manufacturer. GKN show a fatherly interest in the project, but Tony Rolt continues to keep control of FF Developments to which GKN pass over any orders “if they are less than 50,000 a year” explains Rolt. Looking round the workshops it may come as a surprise to many to see just how many people are interested in paying £1000 (or more) to have the full four-wheel-drive treatment on their road cars. Patting the roof of a Capri, Major Rolt quipped “this fellow comes from Switzerland and uses it a lot in the snow. He gets a great deal of pleasure from stopping to help Porsche drivers to fix their chains and then shooting off away up the road!”

Despite his all-consuming involvement with four-wheel-drive systems, Tony Rolt remains an ardent motor racing enthusiast and a great supporter of his son, Stuart, who has just started in Group 1 with a 3-litre Capri. “Really, I find saloons rather more stimulating than formula cars nowadays,” he remarked. Then, with a flicker of pride on his face, he added, “He’s done eight races in that Capri now and he’s only once touched another competitor. That’s not bad for Group 1, is it?” Not bad at all, in fact, and a virtual guarantee that the military bearing of Major Tony Rolt will continue to be seen at race circuits all round this country, his effervescent enthusiasm for cars and motor racing unlikely to wane. A.H.

https://www.motorsportmagazine.com/arch ... emembered/Swiss Timing: Jo Siffert remembered

Author David Tremayne

IN 1948 at Bremgarten a 12 year-old Swiss boy watched, entranced, as a Frenchman wove his magic driving a Gordini. The boy’s name was Joseph Siffert, the Frenchman’s Raymond Sommer. Coeur de Lion, they called the latter, Lionheart. It was his name long before anyone ever thought of coining it for Nigel Mansell, and Sommer was an artist, a man to whom the manner in which the game was played was more important than the result derived, provided he could always look himself in the eye and know he had driven his machinery to the utmost.

Sommer then had barely two years to live, perishing at Cadours when his 1100cc Cooper crashed, but his spirit would live on in the skinny boy. Already he knew what he wanted to do in life. He would race. “I shall drive like Raymond Sommer,” he said to his father Alois that day. “I shall attack!”

And attack Seppi always did, just as he was attacking right to the very end of his life, 20 years ago at Hawthorn Bend at Brands Hatch this month. He knew no other way.

He came from a poor family, and supplemented his income by selling rags before he graduated to trading in motorcycles and then cars. As an under-age driver he was twice chased by the police, and neither time could they catch him! Even as a professional racer, he still loved buying and selling.

Swiss F1 writer Adriano Cimarosti was close to him in those difficult years. “I liked him very much, and the thing I will remember most was his very strong will. He could make the impossible things happen in life because of his will.

Jo Siffert 1968 British GP

First F1 victory came Rob Walker at Brands Hatch ’68

“In 1961 he had just bought his Lotus 18 in Britain and was bringing it home to do the hillclimb at Ollon-Villars, and he came to the border on the Sunday morning of the race. They said they could not allow him to bring the car in that day, come back tomorrow. Of course, that was no good, but they would not budge. So Seppi called the Swiss President President Bourgknecht who was also from Fribourg and asked for his help. It was all arranged! That was typical of Joseph, that ability always to find a solution.

“His prize money was all that took him to the next race. His group would buy satchels of food because it couldn’t afford to eat in restaurants. The first time he went to Enna and beat Clark they had just enough money for the fuel to get to Sicily. They put the car on the ferry and ran off, hoping to avoid paying for their ticket, but they announced over the loudspeakers that the ship wouldn’t leave until the owners of the racing transporter had paid up! After that they had absolutely nothing left. When Seppi won the race they went on a wild party in a restaurant!”

“He had to pay for his racing so he sold road cars — he would drive right through the night and arrive just in time for practice, tired,” recalls his former chief mechanic, engine builder Heini Mader. “Then he’d practice and if he didn’t qualify he’d be off in his car to sell more cars, to pay for the next race.”

“He was a very positive and optimistic character,” said his biographer and close friend, Grand Prix writer Jacques Deschenaux “He had had such a hard life as a child, but even when he had big money problems he was always positive. He was an incredible worker. Sometimes we would drive together right across Switzerland just to find a special door for a car he was selling, just to win him 50 Swiss francs.”

Jo Siffert was an easygoing, impulsive racer. At times situations upset him, but there was never any side to him. He spoke his mind, said what needed to be said, and then it was forgotten. He was too competitive to make close friends with his rivals, but his friendships away from racing were strong. The sculptor Jean Tinguely also came from Fribourg, and when he died just before this year’s Italian GP, his funeral emulated Seppi’s through their native streets.

“Jean was a good influence developing Seppi’s mind beyond motor racing,” says Deschenaux. “He would often arrange his own calendar around Seppi’s racing commitments.”

“15,000 people turned up for the funeral and Jean’s cortege followed the same route. He wanted people to be emotional, but not sad. Seppi’s funeral had been so sad. After Jean’s ceremony all of the people were fed — there was a fantastic spirit.”

Winning was everything to the spontaneous Siffert, the man who brought Marlboro into F1, but Mader remembers: “Seppi took his racing seriously but liked to laugh and have fun. He didn’t ever want to turn into some sort of sad professional.”

One of Deschenaux’s stories encapsulates Siffert’s racing philosophy. “At the 1971 Spanish GP I arrived in Barcelona on the Friday at six in the evening and Seppi, of course, was already there after first practice. He said: ‘Come with me. No questions,’ and rushed me to Porsche’s private plane. We flew to Le Mans and the next day he calmly took part in the April test and hit 400km/h on the Hunaudieres in the 917, before we jumped back into the plane and flew back for the final practice in Barcelona! There was never enough driving for him!”

Jo Siffert Brands Hatch 1971

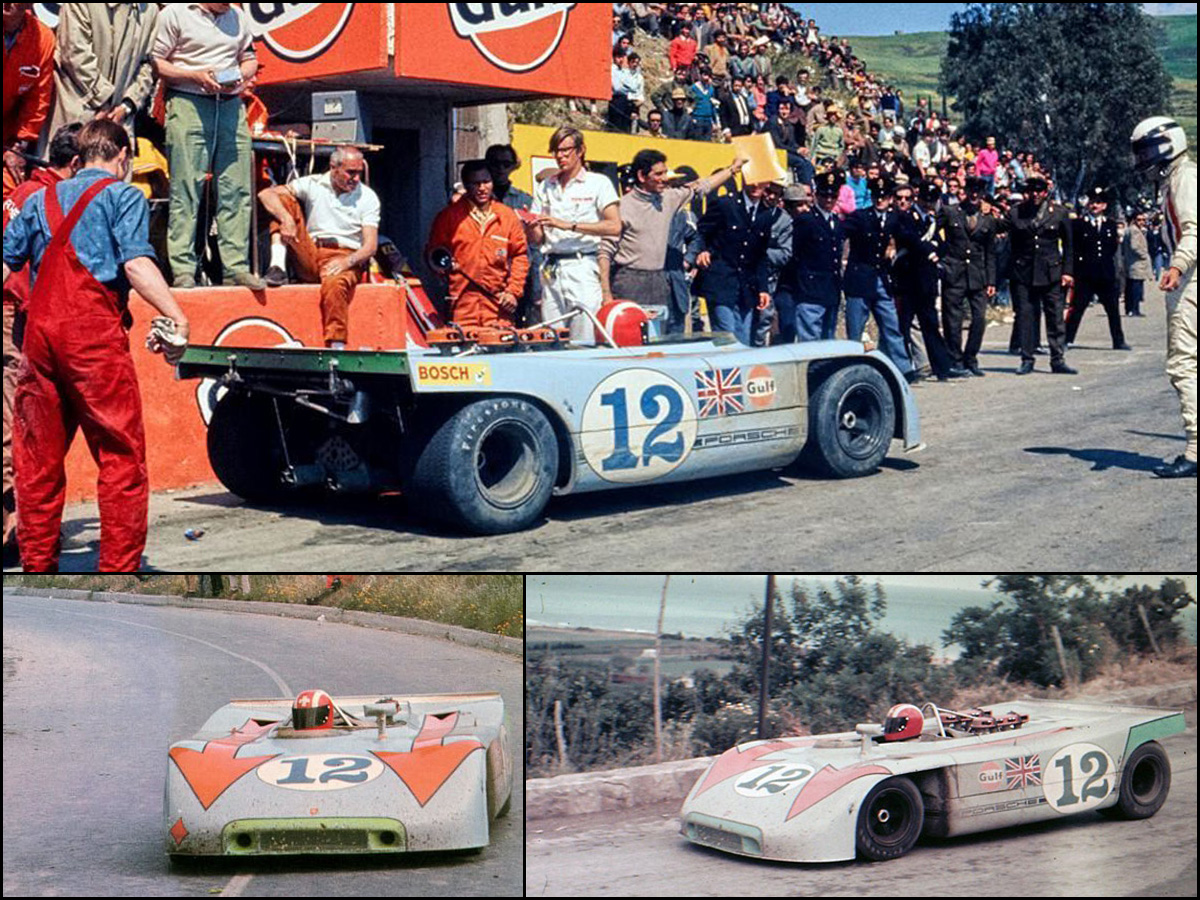

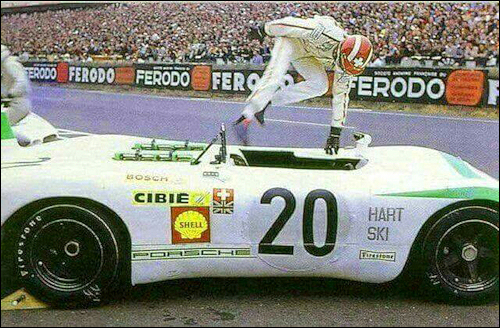

Siffert also made his name in sports cars, seen here driving a Porsche 917 for JWA at Brands Hatch in 1971

From motorcycles he graduated to Formula Junior, then F1 with a 1500cc engine in his Junior Lotus. It was clear he was quick, and when the organisers of the American and Mexican GPs in 1964 refused him an entry unless he could align with a team such as Rob Walker’s, a fresh die was cast.

“Seppi was one of my greatest friends,” says Rob without hesitation. “We used to have such parties together. At the opening of his garage in Fribourg we had a rip-roarer until five in the morning, and then by six thirty he was off on work somewhere.

“His first race for me was Watkins Glen in 1964 alongside Jo Bonnier. He finished third. I was highly impressed and signed him for 1965.

“At Goodwood that April he had this dreadful accident when he thought the whole of the chicane was movable but only half of it was and he hit the other half, which was brick. He kept complaining about a stiff back, and it turned out that if he hadn’t been on his back the whole time he’d have been paralysed. He had damaged a vertebrae but initially the doctors had told him to stop moaning. He was determined to be ready for Monaco and wanted to get back home to his own doctor.

I followed the ambulance to London Airport and there this enormous matron looked at this skinny little driver and said: ‘Did you have a little accident on your bicycle over the holiday weekend?’ Seppi’s English wasn’t very good then and he just smiled at her, but then the head of Swiss Air arrived and threw up his hands and told him he had cleared the whole aircraft for him, the whole back end. The matron was just amazed. The man was bowing to Seppi, whom she had thought was just a boy. It was one of the funniest sights, her eyes were popping out!

“The great thing was that having had Stirling in the team I had learned everything I knew from him. Before him I had had no experience. Having learned it all from Stirling I could tell Seppi and he’d listen.

“At Syracuse Stirling always said that if you got a break, just go for it. Seppi led John Surtees and Jimmy Clark there in April 1965 and there was a fast corner after the pits which it was just possible to take flat. Bonnier managed to let Seppi through before it as they lapped him, and then held them up a little. With a two second lead Seppi really went for it and was pulling away until he jumped too high over a brow 10 laps from the end and the engine blew when the car jumped out of gear.”

Later that year he repeated his 1964 triumph over Jim Clark in the Gran Premio del Mediterraneo at Enna, beating the Scot to the line by three tenths of a second, precisely three times the previous year’s margin! There were some nasty suggestions on both occasions, but Mader refutes them quickly.

“Both times when he beat Jim Clark Colin Chapman just couldn’t understand. There was all sorts of talk, but there was no way BRM would have let me do 2.2 litre engines! No, the secret of the first year was luck. And the second time we knew from the first year how the engine had progressed. We had just the right gear ratios. The BRM was better adapted to the circuit than the Coventry Climax. Even Jim Clark could do no more than put his foot down flat on the throttle there…”

Rob and Seppi always had a full relationship, and after struggling with the awful Cooper Maserati in 1966 and ’67 Seppi was rewarded as Rob bought a brand new Lotus 49 for the 1968 season. In practice for the Race of Champions, however, he crashed it, and to make matters worse the remnants, plus Rob’s 1.5 litre Grand Prix Delage, were then destroyed in a garage fire. Seppi was mortified by his mistake.

“After 40 laps of testing he was right on the lap record. Then in practice it had been raining but had dried out, all except a patch at Surtees. He was literally warming up his tyres when he just lost it there and split the car in half. He had a message pad on a bit of elastic that he carried in his overalls pocket and he’d pull it out and write things on it. When people asked him what had happened he just pulled it out, and on it he had written: ‘Merde alors!”

The Kentish circuit was to bring him better fortune later that year when he vanquished Chris Amon’s Ferrari to win an emotional British GP. The new 49B had literally been finished in the paddock.

Jo Siffert BRM 1971 Italian GP

Move to BRM didn’t bring results he craved and stoked rivalry with Rodriguez

In Canada there was another flash of his brilliance when he qualified on the front row with Amon and Rindt and diced for the lead and set fastest lap before retiring. Then in Mexico he started from the pole.

“He was fastest by half a second,” chuckles Rob. “He had won pole because on one lap his throttle had stuck and he’d had to take the corner at the end of the pit straight flat. When he found it was possible he did it every lap.”

He made a bad start, but pulled back into the lead in a superb drive, until a screw worked loose in the throttle slides and he lost two and a half minutes in the pits. After that he smashed the lap record on his way to sixth place.

Brands Hatch 1968 apart, Jo Siffert’s greatest day came at the Osterreichring on August 15 1971, when he drove his Yardley BRM to a stunning victory from pole position after leading every lap, setting fastest lap, and fending off a late challenge that saw Emerson Fittipaldi carve 24s from his majestic lead when the BRM developed a puncture.

“That was a wonderful race,” says Deschenaux warmly. “It was the first time his mother had flown to a Grand Prix, and he told her to wear something on her dress to let the cabin staff know she was a first time flier, so they would be nice to her. He was always joking, but only nice jokes. It seemed such a long race, and of course he did everything, made the Grand Slam!”

1971 had taken him into the camp of Pedro Rodriguez when he joined BRM. The two were already team-mates in the JW Automotive Porsches, and it was an uneasy alliance.

“They didn’t really like each other,” Deschenaux confirms. “They were too alike! At the Spa 1000kms in 1970 they clashed, and again in 1971 they rubbed doorhandles going down the hill to Eau Rouge and for the first 500 kilometres they were never more than a second apart, at 250 km/h! After that they switched to their co-drivers; Pedro to Leo Kinnunen, Seppi to Derek Bell. Derek lost 10s to Kinnunen in the first lap and then David Yorke signalled him to hold position.

Seppi told Yorke he wanted to win, what was he doing? He was really mad! He dragged me down the pit lane — JW’s pit was at the top — and down to Claude Haldi’s pit. We grabbed his signalling board and so Derek got an official board from Porsche at the top of the hill and another from us at the bottom, urging him on! Seppi was ready to take over from Derek when the two Porsches came in again, but where Pedro resumed from Kinnunen, Yorke wouldn’t let Seppi out. He told him he had already driven for 500 kilometres, and that he couldn’t drive again that day.

“I’m sure Yorke was right, but Seppi was so disappointed. He was crying with frustration when Pedro and Leo won…”

“Seppi and Pedro never actually hated each other,” says Rob Walker, “because Seppi never hated anyone. But Seppi had come into JW and BRM and pushed Pedro to his limit. They were just very similar characters, too similar to become friends, really.”When Pedro was killed at the Norisring in the week between the French and British GPs, Siffert was left to don the Mexican’s mantle at BRM.

Jo Siffert 1971 Austrian GP

En route to his second and final F1 win at Austria ’72

“He didn’t want to do the race,” says Deschenaux of the event at Brands Hatch in which he perished. “We were together in Fribourg and he told me he was too tired. He was doing F1, sportscars with JW, Can-Am with Porsche. Three series! That year he did 45 races!”

October 24 1971 was a beautiful day at Brands. After an awful start from pole position he was fighting back in fourth place, demonstrating for the last time that indomitable will, when the BRM crashed going down Hawthorn Hill.

What went wrong? “He had a brush with Ronnie Peterson on the start-line,” said former BRM team manager Tim Parnell. “I was there, and it was one hell of a bump,” recalls former MN Editor Alan Henry. “He had all four wheels off on the inside and for a moment it looked like the Lafitte accident later did.”

“We think that clash broke the bracket that held the radius arm,” continued Parnell. “It broke going into Hawthorn. You know, the thing was I had a lot of letters from fans afterwards, and one was from a spiritualist who said something broke behind Seppi’s left shoulder. And that’s exactly what did happen. It was spooky. He hit a bank, the car rolled over in flames and he died through lack of oxygen. His only injury was a fractured ankle.”

On that stark autumn day the sky was utterly clear. Those who were there recall the chilling silence that fell when the racing engines suddenly stopped, and the thick, vertical column of black smoke that reached up into the blue. The little Swiss with the darting eyes, the nose for a deal and the famous red helmet with its white stripes and white cross, was gone.

The fans held him in genuine affection. “He was,” said Parnell, “a wonderful man. When he’d come into the pits you’d see the aggression just drain away and he’d become again the gent that he always was.” — DJT

https://www.f1forgottendrivers.com/driv ... h-koinigg/Helmut Koinigg

Bio from Stephen Lathamq

Helmuth Koinigg was born in Vienna, Austria on the 3rd November 1948 and spent most of his childhood in the Styrian mountains, where he became so proficient at skiing that he was selected as a member of the Austrian national junior B team. He studied engineering and journalism and in 1966 lived and worked for several months in Sweden.