Bottom post of the previous page:

On This Day..... 26th February 1908...........Jean-Pierre Wimille was born

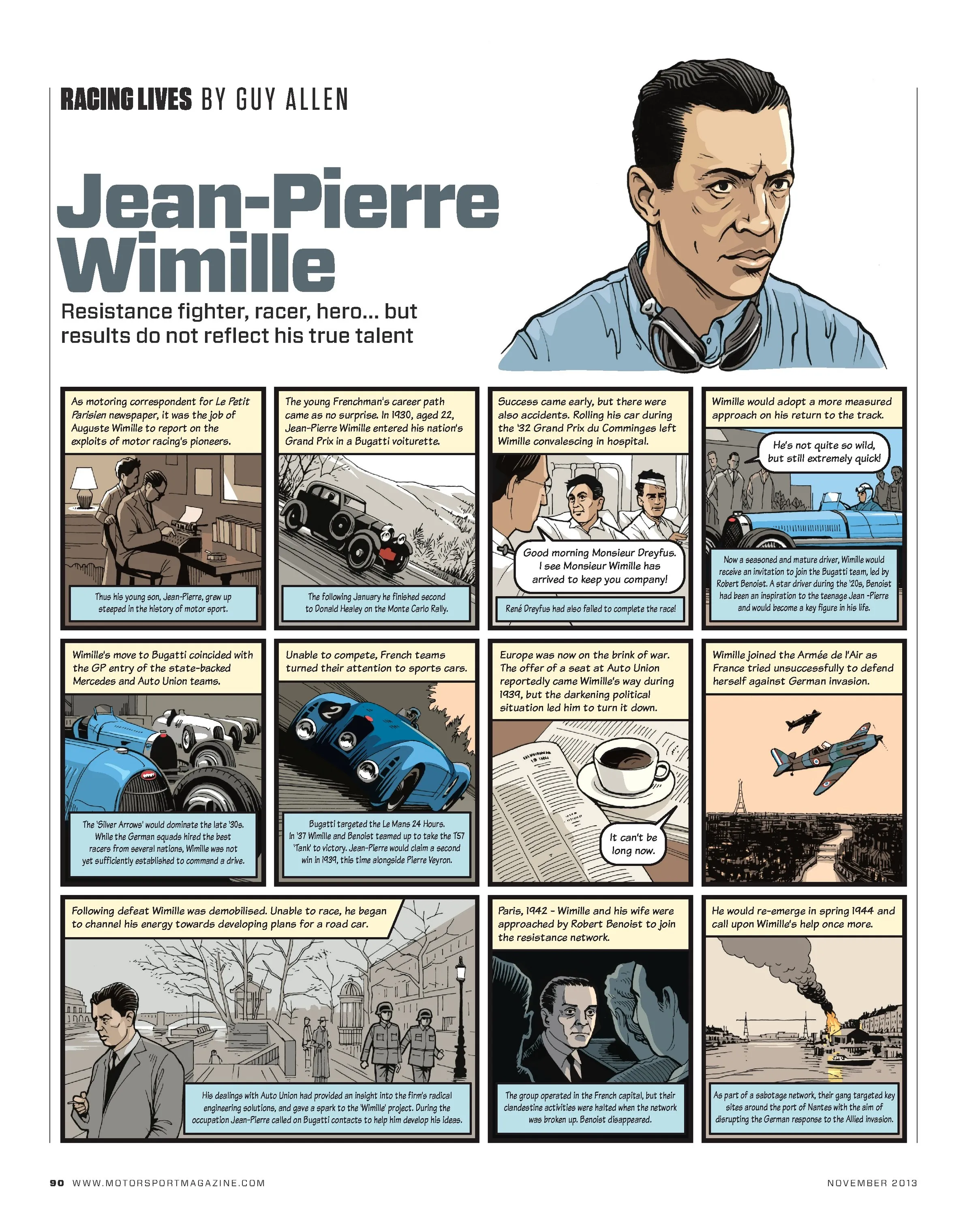

Something of a hero, who sadly died the year before the advent of the World Drivers Championship in 1950. But Wimille was so much more thsn a racing driver of note.

He was a notable French Resistance fighter as well as a pre-war racing ace.. He was a hero both on and off the track. Sadly, the Frenchman's results do not reflect the true scale of his talent.

Born in Paris, France to a father who loved motor sports and was employed as the motoring correspondent for the Petit Parisien newspaper, Jean-Pierre Wimille developed his fascination with racing cars at a young age. He was 22 years old when he made his Grand Prix debut, driving a Bugatti 37A at the 1930 French Grand Prix in Pau.

Driving a Bugatti T51, in 1932 he won the La Turbie Mountain Race, the Grand Prix de Lorraine and the Grand Prix d'Oran. In 1934 he was the victor at the Algerian Grand Prix in Algiers driving a Bugatti T59 and in January of 1936 he finished second in the South African Grand Prix held at the Prince George Circuit in East London, South Africa then won the French Grand Prix in his home country.

Still in France, that same year he won the Deauville Grand Prix, a race held on the city's streets. Wimille won in his Bugatti T59 in an accident-marred race that killed drivers Raymond Chambost and Marcel Lehoux in separate incidents. Of the 16 cars that started the race, only three managed to finish.

In 1936, Wimille traveled to Long Island, New York to compete in the Vanderbilt Cup where he finished 2nd, behind the winner, Tazio Nuvolari.

Wimille also competed in the 24 hours of Le Mans endurance race, winning in 1937 and again in 1939. In the 1937 win he shared a Bugatti "Tank" with Robert Benoist. This victory marked the start of a great friendship between the two men.

When World War II came, following the Nazi occupation Wimille and fellow Grand Prix race drivers Robert Benoist and William Grover-Williams joined the Special Operations Executive of the French Resistance. Of the three, Wimille was the only one to survive.

Jean-Pierre Wimille married Christiane de la Fressange with whom he had a son, François born in 1946. At the end of the War, he became the No. 1 driver for the Alfa Romeo team between 1946 and 1948, winning several Grand Prix races including his second French Grand Prix. Jean-Pierre Wimille died at the wheel of a racing car during practice runs for the 1949 Buenos Aires Grand Prix.

Here is a illustrated comic like strip of his life story published in Motorsport Magazine. If you want to read more of Wimille an his fellow Grand Pric driving resistance fighters I highly recommend Joe Sawards fine and painstakingly researched book the Grand Prix Saboteurs.

https://www.motorsportmagazine.com/arch ... ife-story/

He won 22 competitions, including some of the most legendary such as the Le Mans 24 hours, the Coupe de Paris, the Grand Prix Dell ‘ Autodromo on the Monza circuit, the European Grand Prix in Spa, the ACF Grand Prix in Montlhéry, among many others. In the Spanish Grand Prix in 1935, he came fourth after a bitter duel, just behind the three super-powerful Mercedes Silver Arrows, leaving behind him the formidable Auto Union V16 driven by the no less formidable Bernd Rosemeyer . Jean Pierre Wimille was well known among the greatest racing drivers in the world.

Some of Jean-Pierre Wimille's race victories:

1932:

Grand Prix de Lorraine

Grand Prix d'Oran

1934:

Grand Prix of Algeria - Bugatti T59

1936:

French Grand Prix - Bugatti T57G

Grand Prix de la Marne - Bugatti T57G

Deauville Grand Prix - Bugatti T59

Grand Prix du Comminges - Bugatti T59/57

1937:

Grand Prix de Pau - Bugatti T57G (The Tank)

Grand Prix de Böne - Bugatti T57

24 hours of Le Mans - Bugatti T57G driving with Robert Benoist

Grand Prix de la Marne - Bugatti T57

1939:

Coupe de Paris

Grand Prix du Centenaire Luxembourg - Bugatti T57S45

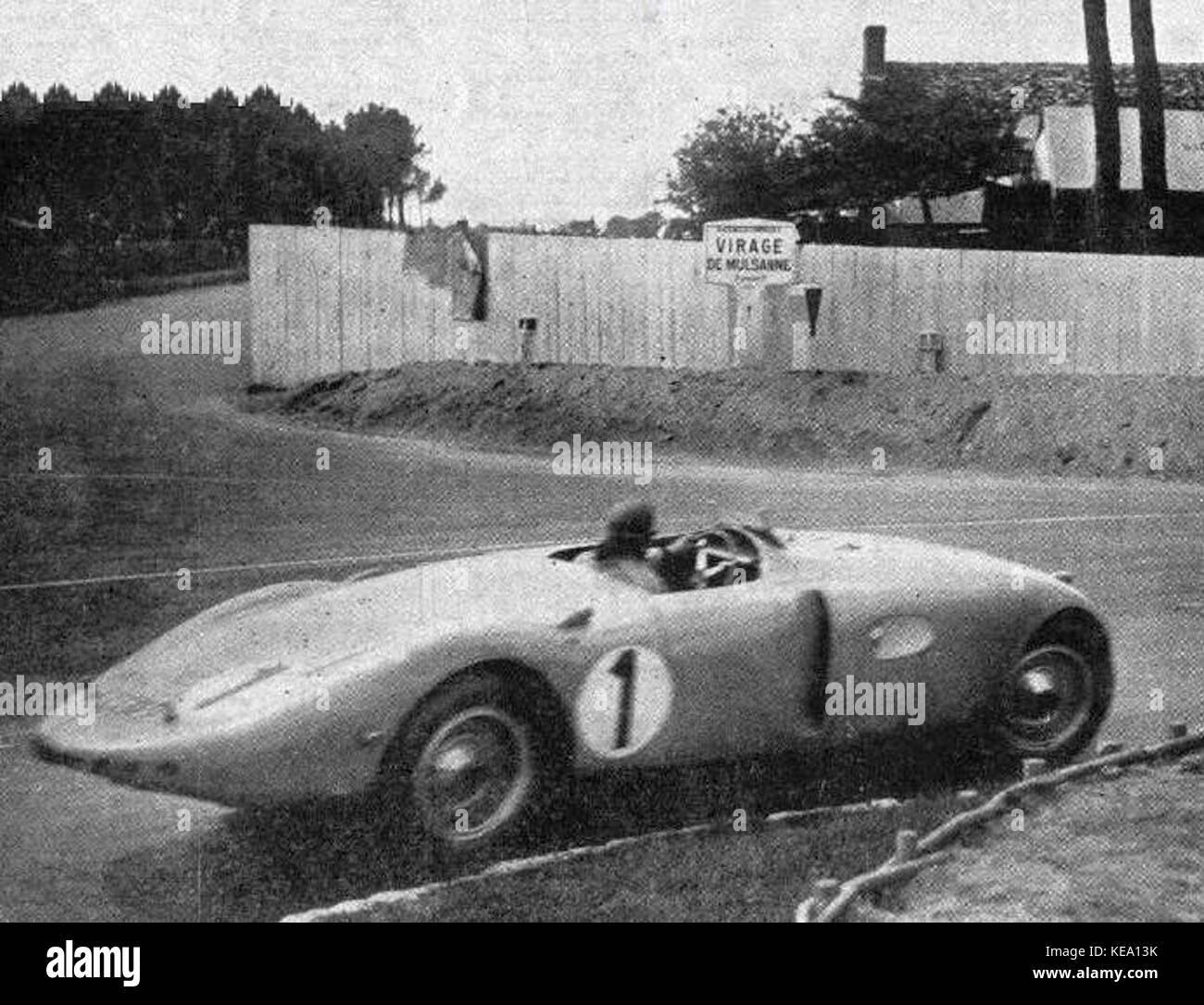

24 hours of Le Mans - Bugatti T57C driving with Pierre Veyron

Post War - 1945:

Coupe des Prisonniers - Bugatti sprint car

1946:

Coupe de la Résistance - Alfa Romeo 308

Grand Prix de Roussillon - Alfa Romeo 308

Grand Prix de Bourgogne - Alfa Romeo 308

Grand Prix des Nations (Heat 1) - Alfa Romeo 158

1947:

Swiss Grand Prix - Alfa Romeo 158

Belgian Grand Prix - Alfa Romeo 158

Coupe de Paris

1948:

Grand Prix de Rosario - Simca- Gordini 15

French Grand Prix - Alfa Romeo 158

Italian Grand Prix - Alfa Romeo 158

Autodrome Grand Prix - Alfa Romeo 158/47

Of course a few additional photos .....

The road cars he started to develop was lets say futuristic given the times.

.https://www.prewarcar.com/retromobile-t ... re-wimilleHe recalled the motor vehicle exhibition of 1937 where he had previously considered the idea of the car of the future. He had sketched out the main lines of this project, shattering the principles of legendary manufacturers. A fast, lightweight car was required with a powerful engine but low cylinder capacity and above all, a structure integrated into a fully aerodynamic body. With the help of his engineer and mechanic friends, he was to realise his plan during this wartime period. A tubular structure, engine and central steering. It was not far from the formula 1 configuration!

A streamlined body was designed with a panoramic windscreen, integrated headlights, independent wheels and electrical control gear box. Three versions were already planned, a 70hp Grand Tourisme; the Sport, with a 100hp V6 1,500cm3 engine; and a 220hp racing version expected to reach speeds of almost 300km/h. This was how the Wimille GT came into being on paper in 1943.

1946, the first appearance of the Wimille 01 prototype was an immediate success. The car’s shape and design was revolutionary. Due to lack of time, the V6 engine planned was replaced by a Citroën Traction engine, which made it possible to conduct initial tests over long distances and present it officially in 1946.

Thw somewhat peculiar looking car in the pic above was equipped with a 2 litre Citroen motor mid mounted.... it produced 56bhp

Amazingly the body had a drag coefficient of only 0.23... it had a top speed of 150 kph wwhich was some accomplishment back in 1946. Most cars today dont meet those minimal levels of drag..

This car below was shown off at the Paris Retromobile Show in 2018

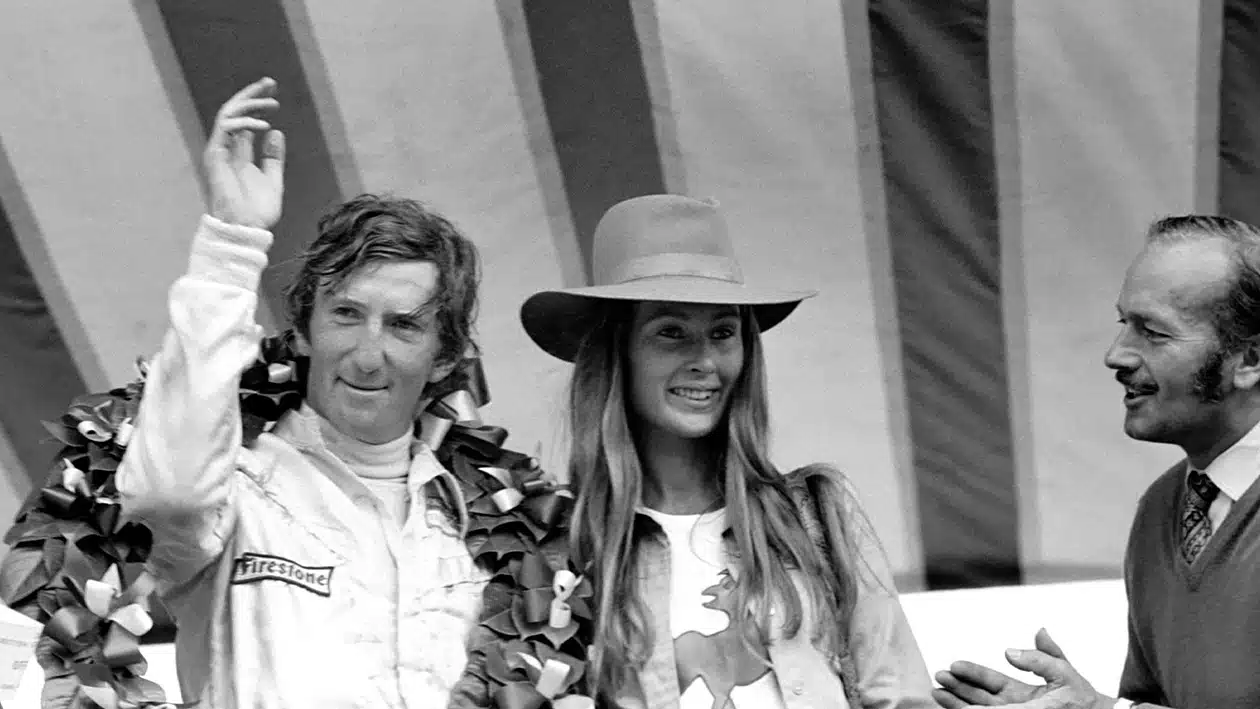

Jean Pierre Wimille and Pierre Veyron winning the 24 Heures du Mans in 1939 in a Bugatti Type 57C

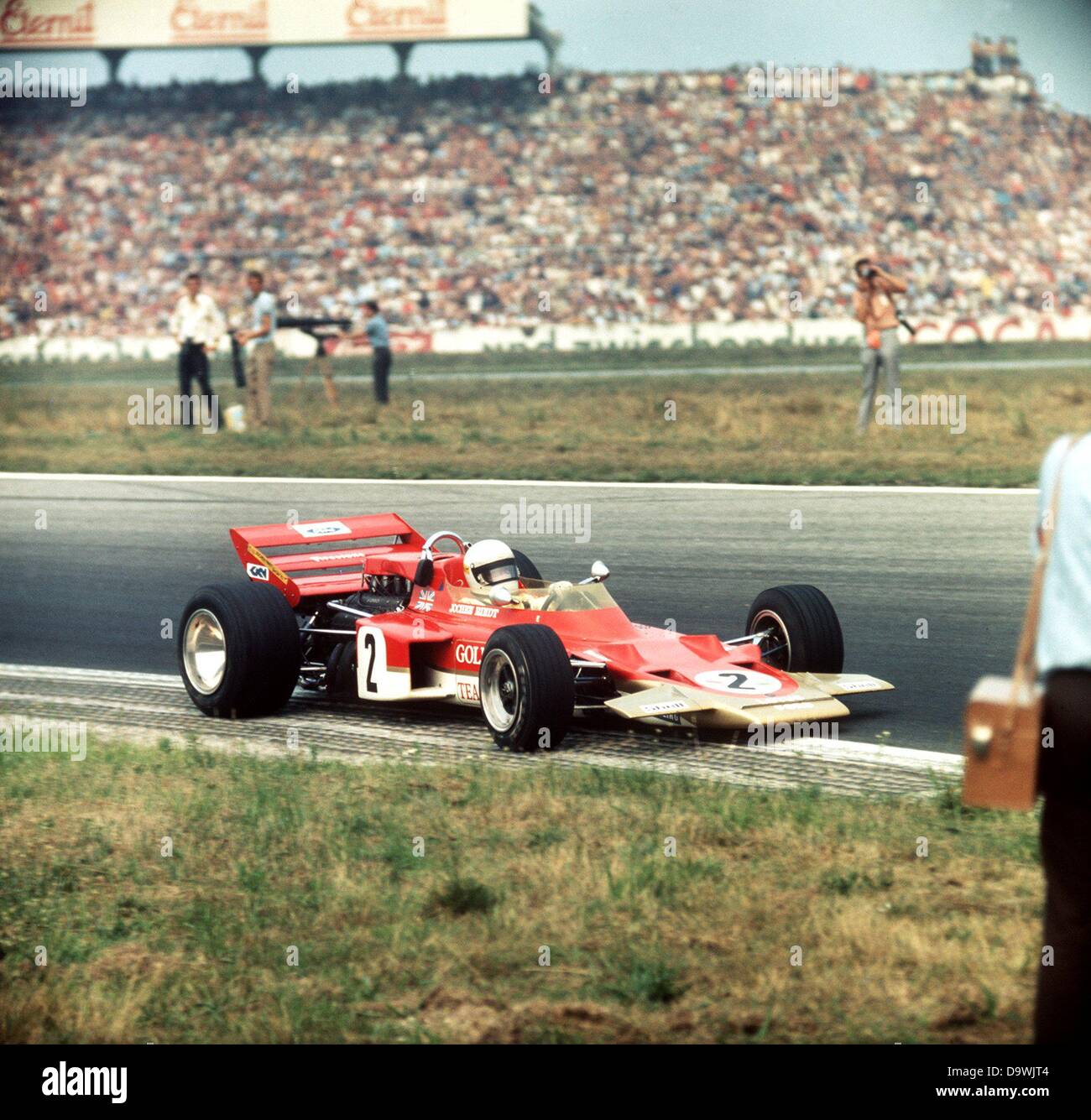

The Le Mans winning Bugatti Tank he shared with Benoist in 1937.

Here is Wimille competing at Prescott in the UK back in 1939

For nfo a pic of the original Bugatti type 32 tank from the early twenties

On July 30, 1939 the Bugatti Owners Club, which often ran competitions at the Prescott Hill-climb, near Cheltenham in the Cotswolds, held an international level event. The recent and double Le Mans winner Jean-Pierre Wimille (above wearing a beret) was entered by the Bugatti factory in a unique monoposto Bugatti 50B which used a supercharged 4.7 liter engine in a modified Type 59 chassis. Jean Bugatti, son of the firm’s founder, was also in attendance. Double rear wheels had been fitted to Wimille’s car, as was common at the time in British hill-climbs to give better traction.

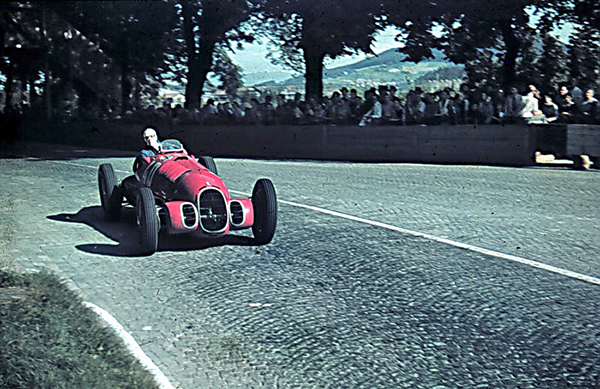

He also drove for Alfa.... Wimille in a 158 in 1948

Jean-Pierre Wimille in an Alfa Romeo 312, a supercharged three litre V12, entered by the works team Alfa Corse, during practice for the 1938 Swiss Grand Prix on the Bremgarten circuit in Bern.