Bottom post of the previous page:

On this day in Motor Racing's past

- erwin greven

- Staff

- Posts: 20075

- Joined: 19 years ago

- Real Name: Erwin Greven

- Favourite Motorsport: Endurance Racing

- Favourite Racing Car: Lancia Delta 038 S4 Group B

- Favourite Driver: Ronnie Peterson

- Favourite Circuit: Nuerburgring Nordschleife

- Car(s) Currently Owned: Peugeot 206 SW Air-Line 3 2007

- Location: Stadskanaal, Groningen

- Contact:

Brian Redman: "Mr. Fangio, how do you come so fast?" "More throttle, less brakes...."

- Everso Biggyballies

- Legendary Member

- Posts: 49195

- Joined: 18 years ago

- Real Name: Chris

- Favourite Motorsport: Anything that goes left and right.

- Favourite Racing Car: Too Many to mention

- Favourite Driver: Kimi,Niki,Jim(none called Michael)

- Favourite Circuit: Nordschleife, Spa, Mt Panorama.

- Car(s) Currently Owned: Audi SQ5 3.0L V6 TwinTurbo

- Location: Just moved 3 klms further away so now 11 klms from Albert Park, Melbourne.

He also got the quickest penalty of any driver in history..... he got pinged for pit lane speeding the first time he left the garage for P1

Actually just realised that was not his race debut weekend that was in 2007. I forgot the pitlane speeding was in fact when he did his first ever FP1, nearly a year earlier at Istanbul in 2006. His F1 career was just 9 seconds old when he was judged to have been speeding on his way out for his first lap. At the time in Istanbul that year he also broke the record for being the youngest driver to take part in a GP weekend (just 19 years and 53 days) so two records that weekend. Of course nowadays 19 is not considered that young.

So before he got his youngest driver to score a point (Canada 2007) he already had two F1 records under his belt.

Actually just realised that was not his race debut weekend that was in 2007. I forgot the pitlane speeding was in fact when he did his first ever FP1, nearly a year earlier at Istanbul in 2006. His F1 career was just 9 seconds old when he was judged to have been speeding on his way out for his first lap. At the time in Istanbul that year he also broke the record for being the youngest driver to take part in a GP weekend (just 19 years and 53 days) so two records that weekend. Of course nowadays 19 is not considered that young.

So before he got his youngest driver to score a point (Canada 2007) he already had two F1 records under his belt.

* I started life with nothing, and still have most of it left

“Good drivers have dead flies on the side windows!” (Walter Röhrl)

* I married Miss Right. Just didn't know her first name was Always

- Everso Biggyballies

- Legendary Member

- Posts: 49195

- Joined: 18 years ago

- Real Name: Chris

- Favourite Motorsport: Anything that goes left and right.

- Favourite Racing Car: Too Many to mention

- Favourite Driver: Kimi,Niki,Jim(none called Michael)

- Favourite Circuit: Nordschleife, Spa, Mt Panorama.

- Car(s) Currently Owned: Audi SQ5 3.0L V6 TwinTurbo

- Location: Just moved 3 klms further away so now 11 klms from Albert Park, Melbourne.

On this Day 18th June 1936...

The late, great Denny Hulme was born.

Gruff and insular, the Kiwi was always a reluctant star who gave away little about himself.

Found an interesting article about Denny, his background and story, in the Motorsport Mag archives, by Adam Cooper, who whilst in NZ on holiday 20 years ago talked to the two women who knew Denny best in search of a clearer picture.

https://www.motorsportmagazine.com/arch ... bear-facts

The late, great Denny Hulme was born.

Gruff and insular, the Kiwi was always a reluctant star who gave away little about himself.

Found an interesting article about Denny, his background and story, in the Motorsport Mag archives, by Adam Cooper, who whilst in NZ on holiday 20 years ago talked to the two women who knew Denny best in search of a clearer picture.

.Denny Hulme: The bear facts

Between this year’s Australian and Malaysian grands prix, Mrs C and I used up a free week with our first visit to New Zealand. On our travels around the wonderful countryside we came across the town of Te Puke. It was a name which I recognised instantly, for it has appeared in every potted CV or profile of its most famous former resident, Denny Hulme. But would anyone here still remember the 1967 Formula 1 world champion?

The first place we tried was an antique shop, where a small photo of a McLaren Can-Am car provided a good starting point. Clearly he had not been forgotten, so I asked the lady behind the counter if there was any memorial to Hulme in town. Only his gravestone, she answered. But would I like to meet Denny’s sister, who worked just up the street?

A couple of minutes later we were sitting in a nearby estate agent’s office chatting to Anita Hulme. And through her we met Denny’s widow, Greeta, who lives an hour or so away. These two lively ladies were delighted to talk about the man they lost to a heart attack in October 1992, and who has never received the recognition that he deserves, especially back in his home country.

The first thing to get right is the pronunciation of his surname. “My father was a very dominant man,” says Anita, who was born three years after Denny. “He always used to say, ‘Don’t knock the ‘l’ out of Hulme!”

Denny’s life was coloured by the fact that his father was an extraordinary character. Clive Hulme was a genuine WWII hero, one of a select group of New Zealanders awarded the Victoria Cross. He won it for his exploits as a sniper in Crete; he’d honed his stealthy approach by catching missing cows back home. He also had unusual powers that, among other things, enabled him to divine water for local farmers.

“I don’t know whether it was inherited or self-taught, but someone told him that blond-haired people with blue eyes were very good at it,” says Anita. “He could also lay a map out and dangle a crystal over oilfields.

“But dad was a very hard man, very hard. The only time I ever remember him giving me a cuddle was when I had my wisdom teeth out and he had to carry me inside! But other than that, he was so hard to live with, he really was. You could never do anything right. He was hard on both of us, and my mum.”

After the war Clive started a trucking business, carting pigs, cows, sheep and even fertiliser around the local area. Later he bought a better truck and began carrying sand. When he fell sick, the teenage Denny had to leave school to take over the driving duties:

There’s no doubt as to where he developed his muscular physique: “He had to load the sand on and off by hand,” explains Anita. “And, if the sea had been in, it was heavy, wet sand.”

Denny Hulme (McLaren-Ford) in the wet 1969 non-championship International Trophy race at Silverstone.

Taking on the wet at ’69 International Trophy at Silverstone

“He’d drive the truck barefoot to the concrete works,” adds Greeta. “If it was overloaded he’d take the long way to avoid the traffic cops. I think that’s where he honed his skills, because it was just a windy dirt road.”

Denny earned very little but, in 1955, by way of compensation, Clive helped him to buy an MG TF. The younger Hulme hitch-hiked all the way to Auckland to pick it up from the boat, and the sportscar became his pride and joy, until he replaced it with a sleeker MGA. From there, his motorsport career had its humble beginnings when he and Anita joined in with the driving tests at the local car club: “They’d put a grapefruit by a post,” she says, “and you’d drive up to it, spear it, reverse back, and drop it into a box!”

Denny and Greeta had been at school together, and her younger sisters had been friends of Anita, but they didn’t really know each other until she returned from infant nursing training to become a registered nurse and they both attended a dance. Afterwards Denny offered Greeta a ride in his MG. She was not at all impressed by the draught and the rattles that came from all corners of the vehicle, but before long they were an item.

Denny’s racing career developed rapidly, from hillclimbs with the MG to the in-at-the-deep-end purchase of a Cooper single-seater, which his father helped to finance. “Dad was right behind him,” says Anita. “Denny was very proud of dad, and dad was very proud of him, but there was no communication between them.”

Denny made an immediate impact when he raced the car at Ardmore, having tested it extensively on local roads: “One of the farmers said he’d put a bloody axe through the car because his cows weren’t milking properly!”

Hulme did so well in his initial outings that he was selected for the 1960 ‘Driver to Europe’ sponsorship scheme, along with George Lawton, who was the son of a local mayor.

Denny had barely travelled within his own country, so the trip to England was a major expedition. It was made a little easier by the fact that his sister had been working in Europe for a year, and was able to help out: “I met them off the train in London with Bruce McLaren, who gave them a Morris Minor to use. We had to go to a lunch somewhere, and I was saying to Denny, ‘Left here, right there’, and he said, ‘I’m not driving in this bloody traffic!’ and made me take over.”

Hulme didn’t know Lawton well, but the pair lived together and were just getting acquainted when George was killed over at Roskilde in Denmark, as Anita recalls: “Denny stopped his car and got out, and George died in his arms. It was a major shock.”

“He still wanted to continue,” continues Greeta, who’d stayed home. “I felt that I had no right to say, ‘Don’t you do it, because I’m frightened.’ It was still something that he had to do. My role was to patch him up and send him back until he’d had enough.”

Hulme finished the season and then returned to contest the New Zealand GP, and took the opportunity to get engaged to Greeta.

“We decided that we still felt the same about each other,” she says. “What’s that saying — absence makes the heart grow fonder? But he decided to continue racing.”

The scholarship funding ended with the GP, and Denny was now on his own. He sold his car, returned to Britain and helped build a new Cooper. Later Greeta embarked on an epic three-day flight to join him, and at first she lived in the bedsit in Kingston previously occupied by Pat McLaren, who’d just married Bruce. She soon found work as a staff nurse, arranging the schedules so that she had weekends off.

Having recently learned to drive Greeta shared tow-car duties as she and Denny toured the Continent. “It was us two versus the world,” she smiles. She still owns their original Ford Zodiac.

Denny Hulme and Jack Brabham (both Brabham-Repco) on the podium after the 1967 German Grand Prix at the Nurburgring.

Victorious in Germany in championship year, alongside team boss / team-mate Jack Brabham

Hulme made good progress on the tracks and subsequently found rides with Ken Tyrrell and later Jack Brabham, for whom he also worked as a mechanic. He was the pacesetter in Formula Junior in 1963, and then shone in Formula Two the following year.

“What came through in the end was that you had to be in the right place at the right time to get the breaks,” says Greeta.

Hulme made his Formula 1 championship debut for Brabham at Monaco in 1965, and finished fourth second time out at Clermont-Ferrand. Inevitably, it wasn’t always easy being in a team owned by the other driver, as Greeta admits: “Denis was always careful that he didn’t tread on Jack’s toes, played it quietly, and did what was expected of him. It was all unspoken.”

He had a great season in 1966, starring in F2 with the Brabham-Honda, finishing second for Ford in the formation finish at Le Mans, and taking four grand prix podiums as he supported Jack’s successful title campaign. But ’67 was to be his year, as he won in Monaco and at the ‘Ring to set up his own title triumph in the last round in Mexico City.

“Denis knew all he had to do was follow Jack around, and he’d have enough points to beat him,” says Greeta. “There was nothing Jack could do. He couldn’t reverse into him and shunt him off!” Brabham finished second and Hulme third, and Denny was world champion by 51 points to 46.

Denny Hulme in his McLaren M8F-Chevrolet, He was a non-finisher due to a broken driveshaft, Mid-Ohio CanAm.

Hulme felt right at home in Can-Am – pictured here for McLaren at Mid-Ohio ’71

For the following season he joined his old pal McLaren, with whom he enjoyed a much closer relationship than he ever had with Brabham. The DFV-powered M7A was a great car and Denny very nearly won the world title for a second time in 1968, late-season victories in Italy and Canada putting him in contention in Mexico once again. On this occasion he didn’t make it, but the Can-Am title provided compensation.

Hulme loved that sports car series, and it was in the States that he picked up his nickname ‘The Bear’. Never one to seek the limelight, he did not have much time for the media, though occasionally he would be difficult purely for his own amusement.

“They would ask him the most stupid questions, just before a race,” remembers Greeta. “I’d learned to leave him be. He did not tolerate fools. But over the years he did mellow a bit.”

“He was a very private person,” agrees Anita. “Everybody walked on eggshells around him, including me! But it’s a family trait, it comes down through the generations. He was happiest when there was no fuss.”

Denny wasn’t in contention for the world championship in 1969, but he did score his fifth GP win in the Mexican finale.

In May 1970 he burned his hands and feet in a methanol fire during testing at Indianapolis, returning to the UK after three weeks on his own in hospital. “It was like having another child, because I had to dress and feed him,” says Greeta.

Then, on June 2, came the shock of McLaren’s death in a testing crash at Goodwood, on a day when Denny should have been driving the car. The Hulmes heard the news when they returned home to Surbiton from a trip to a Harley Street doctor.

“He was crying. Inconsolable,” Greeta recalls. “It was the end of the world. His family had never shown any emotion whatsoever, so it was weird.”

She adds that had they not been committed to the building of an expensive new house, Denny might have given up and returned straight to New Zealand. But he had other reasons for staying, too. “He realised that Bruce wouldn’t have wanted all his efforts to have been sold off or gone in a Dutch auction. They all looked to Denis.”

Now Hulme had to find the strength with which to give the team a direction. He returned to the cockpit far earlier than he should have, and was in terrible pain. But Greeta kept replacing the bandages, and his heroics helped to keep Team McLaren afloat — and won him a second Can-Am title.

Into the early 1970s Hulme, although usually still a front-runner, faded as a force in grand prix racing. He had two young children, Martin and Adele, and later freely admitted that he began to take fewer risks, driving well within his limits. The string of fatal accidents had affected him. There were still occasional grand prix wins when everything fell in his favour — Kyalami in 1972, Anderstorp ’73 and Buenos Aires ’74 — but he was more aware than ever before of the dangers.

The final straw was the death of friend and former team-mate Peter Revson in testing at Kyalami in early ’74. He saw the immediate aftermath of the accident, and his own overalls were bloodied. He knew it was time to stop.

Denny Hulme (McLaren-Ford) in the pits before the 1973 Spanish Grand Prix in Montjuich Park.

Hulme led McLaren team after its founder’s tragic death

“He thought that enough was enough,” says Greeta. “He asked, ‘What am I trying to prove?’ But he never said anything; he kept it quiet until the last race and, when the car broke down, he said that was it.”

Denny was only 38 when he contested his final grand prix at Watkins Glen in 1974, but he looked a lot older. “Everyone used to say that he was my father!” jokes Anita. “My grandad was bald, dad was bald, and Denny was headed that way.”

He stayed in Europe in 1975, travelling to races as the representative of the GPDA, before heading back to New Zealand the following year. He didn’t stay away from the cockpit for long, and was soon happily accepting invitations to race touring cars, becoming a regular at Bathurst.

As Group A took off worldwide so his profile rose again, and he raced extensively in Europe with a TWR Rover, famously winning the Tourist Trophy at Silverstone in 1986 alongside Jeff Allam. Later he was also drawn to truck racing, enjoying both the monster machines and the unpretentious camaraderie among his fellow competitors.

But what he perhaps appreciated most was the recognition he now enjoyed from the historic racing world; he was stunned by the affection that fans still held for him in Europe and the USA. Occasionally, he had a run in his own McLaren M23/1, which he’d shipped back home. He also tracked down and restored his original MG TF.

But life was to change forever on Christmas Day, 1988. The family had just enjoyed a happy lunch at Lake Rotoiti when their world was shattered; Denny’s 21-year-old son Martin died in a diving accident, despite desperate efforts to revive him. Denny had recently grown closer to Martin, and had proudly shown him off at the Australian GP just a few weeks earlier. He was torn apart by the loss, which also created a divide between him and Greeta. He subsequently left home.

Greeta returned to nursing, tried to sort her life out, and made the most of her new situation.

Meanwhile, Denny was at times a troubled man during the last few years of his life. He had some stressful financial issues to deal with, and his personal relationships were complicated — he was never actually divorced from Greeta, and they remained in touch.

By 1992 he found himself living back with his mother. What nobody really knew, but some suspected, was that his health was deteriorating.

“My mum told me,” says Anita, “that she did not know what to feed him: ‘He says everything I cook him is giving him indigestion.’ Before going to Bathurst he’d gone swimming to get fit, and he’d sat on the side breathless.”

More through chance than planning, the 1992 Bathurst 1000 turned into a Hulme family reunion. Anita made the trip along with her daughter and two sons — who’d never been to a race — and they were joined by Denny’s mother and his daughter Adele. Only Greeta wasn’t there.

Denny Hulme McLaren 1974

Hulme knew time was right to exit F1 by ’74

Denny was driving a Benson & Hedges-backed BMW M3 for his old chum Frank Gardner, and initially there seemed to be nothing untoward. As the race went on a thunderstorm passed through, and Denny radioed in to say that he was having trouble seeing. His pit assumed he was talking about the soaked windscreen. It was much more serious than that.

“I’d noticed he hadn’t come round,” says Anita, who was in the grandstand. “And the public address system said that he had kissed the wall and stopped at the side of the track. I said to mum, ‘I think he’s had a heart attack’, but I didn’t think it was going to be a fatal one, even when we were all there waiting at the hospital.”

But Denny was dead even before the marshals reached his stranded car. He was buried in Te Puke, where dad Clive and son Martin had been laid to rest.

“He was so upset after Martin’s death,” says Anita. “He used to go and sit in the cemetery.

“I know that he died of a broken heart.”

https://www.motorsportmagazine.com/arch ... bear-facts

* I started life with nothing, and still have most of it left

“Good drivers have dead flies on the side windows!” (Walter Röhrl)

* I married Miss Right. Just didn't know her first name was Always

- Starling

- Bronze Member

- Posts: 187

- Joined: 2 years ago

- Real Name: Paola

- Favourite Motorsport: F1

- Favourite Driver: Ayrton Senna

- Favourite Circuit: Monza, Montecarlo

- Car(s) Currently Owned: Nissan Micra (vintage in 3 yrs)

Denny Hulme was one year older than my late beloved dad. I never followed him: at first I was too young, later there were more fascinating drivers to follow. And yet, listen to this: one day I pick up Autosprint and on the cover is HULME DIES! I felt a shiver, as though in all those years I'd been aware of him, and now unconsciously mourned him. The brain (and the passion for racing) is a mysterious thing. Love ya Denny, New Zealand forever (my nickname Starling is for a fictitious NZ driver). <3

Nada pode me separar do amor de Deus.

-

Manfred Cubenoggin

- Platinum Member

- Posts: 834

- Joined: 20 years ago

- Location: Oshawa, Ontario

Spare a thought today for Piers Courage who was killed this day, June 21, in 1970. Fifty-two years. Seems like yesterday.

RIP, PC.

RIP, PC.

Miles to go B4 I sleep

- Everso Biggyballies

- Legendary Member

- Posts: 49195

- Joined: 18 years ago

- Real Name: Chris

- Favourite Motorsport: Anything that goes left and right.

- Favourite Racing Car: Too Many to mention

- Favourite Driver: Kimi,Niki,Jim(none called Michael)

- Favourite Circuit: Nordschleife, Spa, Mt Panorama.

- Car(s) Currently Owned: Audi SQ5 3.0L V6 TwinTurbo

- Location: Just moved 3 klms further away so now 11 klms from Albert Park, Melbourne.

In case people have missed it some additional reading and pics about Piers Courage here: viewtopic.php?f=18&p=428710#p428710Manfred Cubenoggin wrote: ↑1 year ago Spare a thought today for Piers Courage who was killed this day, June 21, in 1970. Fifty-two years. Seems like yesterday.

RIP, PC.

* I started life with nothing, and still have most of it left

“Good drivers have dead flies on the side windows!” (Walter Röhrl)

* I married Miss Right. Just didn't know her first name was Always

- Everso Biggyballies

- Legendary Member

- Posts: 49195

- Joined: 18 years ago

- Real Name: Chris

- Favourite Motorsport: Anything that goes left and right.

- Favourite Racing Car: Too Many to mention

- Favourite Driver: Kimi,Niki,Jim(none called Michael)

- Favourite Circuit: Nordschleife, Spa, Mt Panorama.

- Car(s) Currently Owned: Audi SQ5 3.0L V6 TwinTurbo

- Location: Just moved 3 klms further away so now 11 klms from Albert Park, Melbourne.

OK a slightly different format today.... instead of picking on some everyday or household name or well known event I am picking on a lesser known name involved in a well known scenario.

On this day, 22nd June 1930

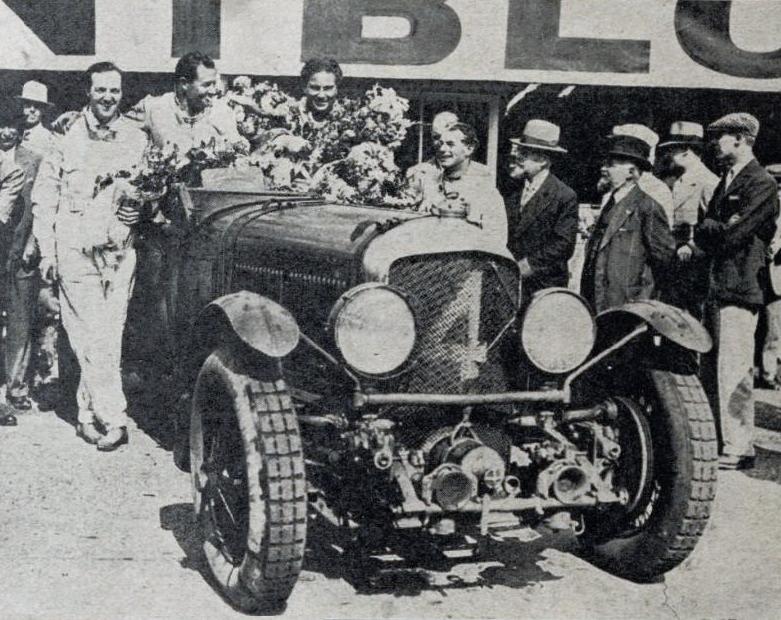

Commander Glen Kidston and Woolf Barnato won Bentley's penultimate Le Mans on this day in 1930

Kidston (second left, sat in car) with Woolf Barnato after winning the 1930 Le Mans

We all know the legend of the Bentley Boys, and indeed of them the likes of Wolf Barnato and Tim Birkin would be perhaps the most famous But I have picked not Barnato, but the lesser known of that 1930 win, Commander Glen Kidston, because he seemed to pack an awful lot in to a relatively short life. And he seems an interesting guy, albeit in a very "how the other half lived" kind of way.

Commander Glen Kidston is best remembered as one of the legendary ‘Bentley Boys’ of pre-war days. Those wealthy, glamorous drivers of the big green cars that upheld British prestige abroad, particularly at Le Mans, where they won five times and got front-page publicity in leading daily papers.

In an age long gone Kidston was one of them, although, in fact, he drove less than some of the others of the famous W O Bentley team, and had adventures in a life packed with incident outside the motor racing scene.

Kidston as well as his wide range of motorcycling and automotive exploits, joined the Royal Navy aged 11, was in WW1 active service at age barely 15, survived a shipwreck, a submarine that sank, a plane crash, held the London to Cape Town Aero Speed record before he was killed in another plane crash aged just 31.

Bill Boddy tells his story, published in Motor Sport Magazine back in 1997, a time when this Bentley win in 1930 was indeed their last win. You and I all now that in 2003 Bentley of course took a rousing 1-2 finish. (Just explaining the reasons for the mention of 1930 in the article as being the last Bentley win.)

For those interested here is an interesting account of Bentley and their racing heritage

. BENTLEY....A HUNDRED-YEAR RACING HERITAGE

On this day, 22nd June 1930

Commander Glen Kidston and Woolf Barnato won Bentley's penultimate Le Mans on this day in 1930

Kidston (second left, sat in car) with Woolf Barnato after winning the 1930 Le Mans

We all know the legend of the Bentley Boys, and indeed of them the likes of Wolf Barnato and Tim Birkin would be perhaps the most famous But I have picked not Barnato, but the lesser known of that 1930 win, Commander Glen Kidston, because he seemed to pack an awful lot in to a relatively short life. And he seems an interesting guy, albeit in a very "how the other half lived" kind of way.

Commander Glen Kidston is best remembered as one of the legendary ‘Bentley Boys’ of pre-war days. Those wealthy, glamorous drivers of the big green cars that upheld British prestige abroad, particularly at Le Mans, where they won five times and got front-page publicity in leading daily papers.

In an age long gone Kidston was one of them, although, in fact, he drove less than some of the others of the famous W O Bentley team, and had adventures in a life packed with incident outside the motor racing scene.

Kidston as well as his wide range of motorcycling and automotive exploits, joined the Royal Navy aged 11, was in WW1 active service at age barely 15, survived a shipwreck, a submarine that sank, a plane crash, held the London to Cape Town Aero Speed record before he was killed in another plane crash aged just 31.

Bill Boddy tells his story, published in Motor Sport Magazine back in 1997, a time when this Bentley win in 1930 was indeed their last win. You and I all now that in 2003 Bentley of course took a rousing 1-2 finish. (Just explaining the reasons for the mention of 1930 in the article as being the last Bentley win.)

https://www.motorsportmagazine.com/arch ... kidston-rnCommander Glen Kidston: submariner, aviator, adventurer and Bentley's last Le Mans winner

W O Bentley thought of Glen Kidston as a driver as fearless as Birkin, yet steady when necessary, and amenable to discipline, always so important when driving for a team. Thus was Glen Kidston the Naval Officer, strong, apt to stand no nonsense, and extremely good-looking, especially in uniform.

He took to riding motorcycles at an early age, of which his first was one of those advanced Belgian FNs with four little finned cylinders in line on the crankcase, and shaft-drive, and was soon into trials and speed-events, his favourite make the Sunbeam. It is said that he only took to cars after winning so many gold medals in the all-night-and-day MCC classic trials that it had become boring! He used to maintain these machines himself, and took part in impromptu speed trials with them while in Hong Kong, the Sunbeam having been part of his ship’s cargo. He rode in the 1921 International Anglo Dutch motorcycle trial, and before that he had won the Arbuthnot Trophy.

However, that is only part of the story. Prior to this Glen Kidston, born to adventures, tough, thickset, with broad shoulders, had decided at the age of 11 to join the Royal Navy. He followed the conventional course, entering the Royal Naval College at Dartmouth and, the passing-out examinations concluded successfully, Kidston became a young midshipman, on HMS Hogue. He was soon to see action at this very young age, because the Hogue was engaged in the Battle of Heligoland Bight, in the summer of 1914, and the following month was sunk, in company with the Aboukir and the Cressy, off the Dutch coast, by torpedoes from enemy submarines.

A party of big game hunters leaves Croydon airport, bound for Africa, 1928. They are Captain Drew (pilot), Mr Whatley (mechanic), Mr Thistlewaite, Mr Brand and Commander Glen Kidston (1899 - 1931). (Photo by Central Press/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Kidston (far right) with a party of big game hunters, preparing to set off from Croydon to African in 1928

Kidston escaped from these sinkings, as he was to do in subsequent desperate situations on land, water and from the air. Instead of being intimidated by his experience of U-boat warfare, the young midshipman sought to retaliate by taking the submarine course, and by 1917 had passed out as a hilly qualified Submarine Officer, having before that served from October 1914 to 1917 with HMS Orion, taking part in the historic Battle of Jutland.

At the conclusion of the war Kidston was with the British prize-crews engaged in the takeover of the surrendered German U-boats at Harwich. In 1919, he served in submarines in the Baltic and the Far East, and was second-in-command of the world’s largest submarine, X-1, surviving a dive from which it proved difficult to resurface after being trapped in the mud on the ocean floor for an alarming number of hours. He then found himself appointed to HMS Dauntless for the Imperial World Cruise.

After the Armistice it was hardly surprising that this experienced and respected Naval Officer should seek exciting sports for relaxation. Of these, motor racing was foremost. But Kidston had also boxed quite usefully in his early Navy days, and was an enthusiastic performer on skis at the winter resorts, engaged in shoots, and fly-fished the fast-flowing Wye, close to the Welsh family seat.

His taste in cars was catholic and ranged from a Salmson and a Baby Peugeot to sports AC and Hillman light-cars, a Chrysler, and a very elegant 37.2hp Hispano-Suiza two-door saloon. I recall being much intrigued by a picture of the last-named photographed on London’s Embankment (in the days when traffic was moderate enough for a pause for this purpose) with its owner at the wheel in naval uniform. This was the 1924 Boulogne short-chassis showcar with Hooper body and much special equipment, which lapped Brooklands at 84mph. Then there were the Bentleys. Kidston ordered his first when he was still a Lieutenant in the Navy, a 3-litre Speed Model with Park Ward body, delivered in 1924. This was followed by an actual 3-litre Le Mans Vanden Plas tourer, in 1926.

In 1925, price being no problem, Kidston had ordered one of the latest 2-litre straight-eight Grand Prix Bugattis from Molsheim, remarking that Ettore Bugatti was one of the only manufacturers who sold cars ready for an amateur to race. He entered for the Grand Prix de Provence, or Hartford Cup Race, to be run over 250km of the new Miramas track in France, changing naval uniform for white overalls, linen helmet and goggles. In this, his very first race, Kidston did remarkably well, getting into the English headlines. Although in the end the 1.5-litre Talbots, running unsupercharged, driven by Segrave and Count Conch, finished first and second, Kidston had led them three times, until forced to come in to rectify low fuel pressure. He resumed, to finish fifth behind Vidal’s 2-litre Bugatti and George Duller, whose Talbot had been delayed when two plug leads came adrift Kidston had been driving for 4hr 10min 50sec, less than 12min behind the very experienced Segrave, beating seven other finishers.

When Lt Kidston brought the Bugatti to Brooklands for the 1925 Easter Monday Meeting it was a centre of interest, because it was the first time one of the new models had been seen there, with the handsome GP body and the aluminium spoked wheels. In the Private Competitors’ Handicap Kidston came in third behind Harold Purdy’s 12/50 Alvis and Jack Dunfee’s Salmson, having made the fastest standing-start and flying-start laps in the race, respectively at 89.41mph and 103.57mph.

1930-LM-Kidston

Kidston about to set off another hunting adventure (date unknown)

At Whitsun, Kidston in his Bugatti was fighting a close run-in to the finish of the Gold Vase race, against the Leyland Thomases of Party Thomas and Capt J EP Howey, and Major Coe’s new 30/98 Vauxhall Wensurn, when Coe risked going high up the Members’ banking in endeavouring to overtake Ramponi’s ancient chain-drive Fiat. The Vauxhall scraped along the Railway Straight corrugated-iron fence as it came off the banking, rebounded onto the track, and overturned, throwing out both occupants. Lt Kidston kept his head (or his ‘cool’, as they now have it) as he had done many times previously and drove through the dust and debris to stay ahead of the two Leylands, Thomas leading Howey after momentarily putting a wheel over the rim of the Byfleet banking in the chase at a lap speed of 125.77mph, the Bugatti’s best lap being at 110.68mph. Quite a race…

In the Gold Cup Race which followed, Thomas and Kidston again swept together off the banking to the finish, the Leyland-Thomas winning by 300 yards after a record lap at 126.41mph, the Bugatti doing 109.46mph. After this Kidston was tying with Thomas for Hartford Cup points put up by TB Andre, who supplied Hartford shock absorbers to most of the Brooklands’ drivers. During 1926 Kidston had gained points with a second place in the VVhitsun Gold Cup race, and first place in a 90mph Short Handicap.

Naval duties kept Kidston away from the track at the end of the year. In November he married Miss Nancy Soames. It was one of the notable social occasions of the year, at St Margarets, Westminster — where else? – the Lieutenant promised his bride he would give up motor racing and sold the Bugatti (XW 9557) to George Duller. As a safer sport he acquired a 14ft National Class Morgan Gyles dinghy, a change from submarining!

The attraction of motor racing was too hard to resist though, and having met W O Bentley, Glen Kidston began his ‘Bentley Boy’ associations by driving at Le Mans in 1929, bringing the first 4 1/2-litre Bentley home to finish second, behind the winning 6 1/2-litre. He was paired with Jack Dunfee (who, let it be whispered, once told me that he found Le Mans easy compared to lapping Brooklands at over 130mph in a heavy car); the Bentleys came home triumphant in 1,2,3,4 formation at the end of the 24 hours. Those were good results, calling for stamina, acceptance of team orders and, one might add, the obvious one of good night-vision.

But it was in the Phoenix Park Grand Prix in Ireland in July 1929 that Glen Kidston pulled out all the stops and gave an exhibition of his ability to drive to the extreme edge when it was called for. He had ‘Old No 1’ Speed Six (the cause of that well-remembered court case of recent memory) and after Birkin in a blower-4 1/2 Bentley had worn down Thistlethwayte’s Mercedes-Benz, there was Boris lvanowski’s 1 1/2-litre Alfa Romeo to catch. Only the Speed Six, of the seven Bentleys which started, could do it. Kidston was equal to the challenge but the melting tar made it just too difficult; the heavy Bentley slid into a bank and the Italian car won by just 14 seconds after 300 difficult miles. But the Bentley made the fastest race time at 79.8mph in this handicap race, compared to Birkin’s 79.0mph.

22nd June 1930: People watching the Le Mans 24 Hour Endurance Race.

The Mulsanne straight during the 1930 Le Mans

Justifiably, Kidston was trusted with ‘Old No 1’ Speed Six Bentley for the 1929 Ulster TT. He once again demonstrated his ability to drive very fast, with Kidston holding the flying Caracciola on the teeming wet road, but this came to an end when the big green car got into a skid he could not control coming down Bradshaw’s Brae, to miss a telegraph pole by the proverbial hair’s breadth and go over the bank after a notably long slide, with the Bentley’s wheels straddling the mound, so that retirement was inevitable. That had happened on lap five, but Bernard Rubin had been caught out on the very first lap when his 4 1/2-litre Bentley overturned; however no-one was much hurt.

That November, Kidston had another narrow escape. He was flying with a German prince from Croydon to Berlin in a Luft Hansa Junkers trimotor monoplane when it flew into a hill near Caterham and burst into flames. Kidston, his clothes alight, kicked out a panel and escaped, the only one of six occupants to do so.

The commander had a crack at the 1930 Monte Carlo Rally with a 6 1/2-litre Bentley saloon, starting from John O’Groats, but it slid into a wall on sheet ice before reaching Glasgow and bent its front axle. For the 1930 JCC Double-Twelve’ Kidston was paired with Jack Dunfee in one of the blower-4 1/2 Bentleys, but it broke a valve. He was back again in the famous and hard-worked Speed Six for that year’s Le Mans race, with none other than Woolf Barnato, the millionaire whose financial intervention, had saved the Bentley company. It was one of Glen’s great successes, when he worked calmly with Barnato and they won at 75.88mph. After which the Bentley company retired from racing and Kidston turned to his aviation pursuits.

I was reminded that when Kidston kept an aeroplane at what is now the Royal Welsh Show Ground at Bath Wells, his sisters would get out a Bentley and try to race him to the family house. In 1930, Lt Commander Kidston entered his D118 Puss Moth G-AAXZ for the King’s Cup race. Later he acquired a white and black Lockheed D1 -1 Special Vega G-AGBK and with it established a record for a commercial aeroplane, by flying from Croydon to Le Bourget with three passengers in 1hr 20min.

22nd June 1930: A group of drivers and racing cars during the Le Mans 24 Hour Endurance Race.

Bentley team cars after 1930 victory

Soon after this, in March 1931, Kidston took off from the military aerodrome at Netheravon with the celebrated pilot Owen Cathcart-Jones in the 420hp Wasp-engined Vega, and with the help of Marconi wireless operators, who changed over at Cairo, set a new England-Cape Town record of 131.8mph for the 7500 miles. The powerful cabin-monoplane had been in the air for a total of 57hr 10min. Incidentally, the hope of building Lockheed Vegas in this country was apparently frustrated by the British aircraft industry.

Sadly, this brave and adventurous man’s career ended when the Lt Commander was flying with Capt Gladstone, over the Drakensberg mountains in Natal, Africa. His DH Puss Moth ZS-ACC broke up and both occupants were killed. The weather was turbulent and it was suggested that baggage in the cabin had broken loose and caused the accident. But after eight similar accidents, investigations showed that, in such conditions, the wing structure could not take the strain. So, through no fault of his own, Kidston, who had survived so many close calls far from home, was killed at the age of 31.

For those interested here is an interesting account of Bentley and their racing heritage

. BENTLEY....A HUNDRED-YEAR RACING HERITAGE

* I started life with nothing, and still have most of it left

“Good drivers have dead flies on the side windows!” (Walter Röhrl)

* I married Miss Right. Just didn't know her first name was Always

- Starling

- Bronze Member

- Posts: 187

- Joined: 2 years ago

- Real Name: Paola

- Favourite Motorsport: F1

- Favourite Driver: Ayrton Senna

- Favourite Circuit: Monza, Montecarlo

- Car(s) Currently Owned: Nissan Micra (vintage in 3 yrs)

Rest well Piers. I wish I had seen you racing.Manfred Cubenoggin wrote: ↑1 year ago Spare a thought today for Piers Courage who was killed this day, June 21, in 1970. Fifty-two years. Seems like yesterday.

RIP, PC.

Nada pode me separar do amor de Deus.

- Everso Biggyballies

- Legendary Member

- Posts: 49195

- Joined: 18 years ago

- Real Name: Chris

- Favourite Motorsport: Anything that goes left and right.

- Favourite Racing Car: Too Many to mention

- Favourite Driver: Kimi,Niki,Jim(none called Michael)

- Favourite Circuit: Nordschleife, Spa, Mt Panorama.

- Car(s) Currently Owned: Audi SQ5 3.0L V6 TwinTurbo

- Location: Just moved 3 klms further away so now 11 klms from Albert Park, Melbourne.

On this Day 27th June 1965

Jim Clark won the first French GP to be held at Clermont-Ferrand.

But today I am not going to post about the event so much as the iconic Clermont Ferrand CharadeTrack it was held on. (AKA Circuit Louis Rosier)

The Clermont-Ferrand grand prix track was five miles long. With 50 corners on an undulating five-mile track, it was no wonder that drivers wore open-face helmets — to throw up on their way down the hills. It separated real drivers from also-rans like no other. Yet it is a track not remembered like many other tracks of yesteryear. Except for those who raced there. With 50 corners in five miles, it was unforgettable.

“It was the best track in France; better by far than everywhere else we went like Rouen, Reims and Paul Ricard.” One of the four most difficult circuits in the world. So said Jackie Stewart.

Just four Grands Prix were held there..... Stewart won two, in 1969 and 1972, while the 1965 inaugural event fell to Jim Clark and the 1970 race to Jochen Rindt.

Four races won by three world champions, the three finest drivers of their era. It was a circuit where precision was everything, a misplaced wheel here spelling disaster there, a place requiring more mental stamina than any other on the calendar with the possible exception of the Nürburgring. It was a beautiful, awe-inspiring place and, while there hasn’t been a race of any description on the full circuit for over a decade, it still is.

A track map showing the layout. The dark outline is the 2.517 mile shortened circuit, used in more recent years for events such as F3. (Sebastien Bourdais won 2 races on it in the 1999 French F3 Championship)

This article about the track was written back in 2000, and comes from the archives of Motor Sport Magazine, when Andrew Frankel revisited the track.

A few extra photos....

Chris Amon Matra 1972. Shoulda Coulda Woulda

Jochen Rindt 1970

Jackie Ickx 1969

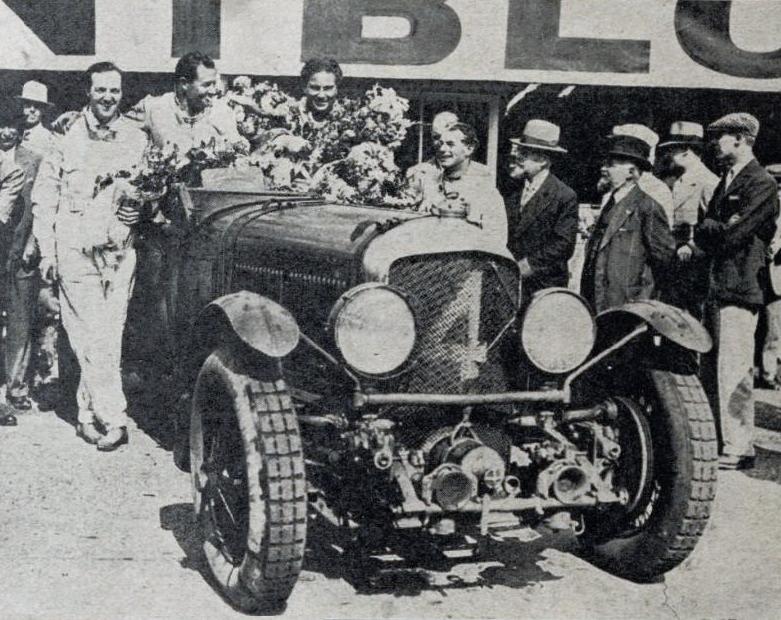

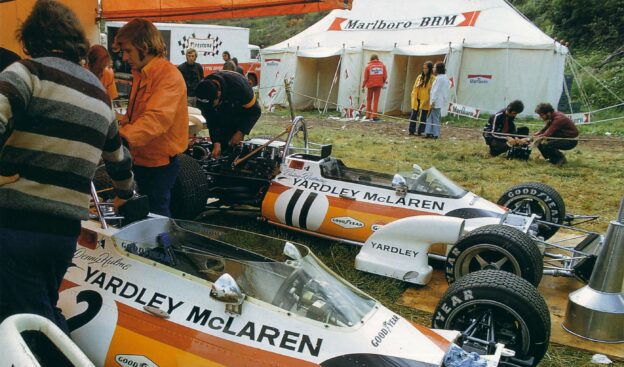

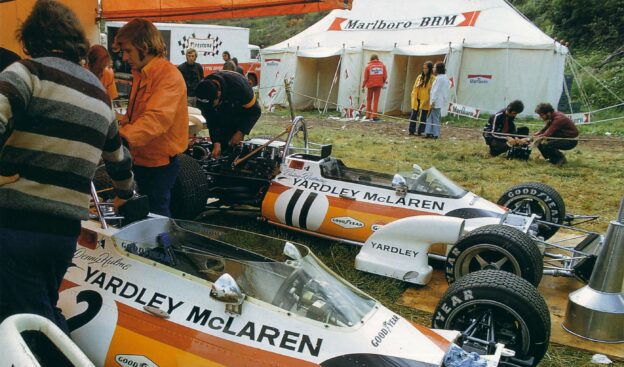

Facilities what facilities! March and BRM Paddock area 1970

Didnt get much better.... above McLaren in 1972

Jim Clark 1965

Helmut Marko BRM 1972

1965

Dave Walker Lotus 1972

John Surtees Ferrari 1965

Jim Clark won the first French GP to be held at Clermont-Ferrand.

But today I am not going to post about the event so much as the iconic Clermont Ferrand CharadeTrack it was held on. (AKA Circuit Louis Rosier)

The Clermont-Ferrand grand prix track was five miles long. With 50 corners on an undulating five-mile track, it was no wonder that drivers wore open-face helmets — to throw up on their way down the hills. It separated real drivers from also-rans like no other. Yet it is a track not remembered like many other tracks of yesteryear. Except for those who raced there. With 50 corners in five miles, it was unforgettable.

“It was the best track in France; better by far than everywhere else we went like Rouen, Reims and Paul Ricard.” One of the four most difficult circuits in the world. So said Jackie Stewart.

Just four Grands Prix were held there..... Stewart won two, in 1969 and 1972, while the 1965 inaugural event fell to Jim Clark and the 1970 race to Jochen Rindt.

Four races won by three world champions, the three finest drivers of their era. It was a circuit where precision was everything, a misplaced wheel here spelling disaster there, a place requiring more mental stamina than any other on the calendar with the possible exception of the Nürburgring. It was a beautiful, awe-inspiring place and, while there hasn’t been a race of any description on the full circuit for over a decade, it still is.

A track map showing the layout. The dark outline is the 2.517 mile shortened circuit, used in more recent years for events such as F3. (Sebastien Bourdais won 2 races on it in the 1999 French F3 Championship)

This article about the track was written back in 2000, and comes from the archives of Motor Sport Magazine, when Andrew Frankel revisited the track.

https://www.motorsportmagazine.com/arch ... nt-ferrandRevisiting the legendary Clermont-Ferrand GP circuit — Track Tests

I’d wanted to go Clermont ever since, in the last series of Track Tests, I reported back from its rival, the circuit at Rouen-les-Essarts. Among the correspondence that came tumbling in were several letters all saying essentially the same thing: That was Rouen, thank you. Now, when are you going to Clermont-Ferrand? The tales that accompanied this common request told of stunning scenery and awesome racing on public roads around two extinct volcanoes. It was a place I had to visit.

View of former Clermont Ferrand Grand Prix paddock

View of the circuit today, from the wasteland that is the original paddock

It’s rather easier to get to now than it was when it opened its gates in 1958. Now you need simply drive to Paris, around the peripherique, leave towards Chartres before spearing south past Orleans to Clermont-Ferrand. The circuit lies in the countryside about five miles to the south-west of the city, outside the pretty town of Royat. On our return leg, the BMW carried us from the circuit to Paris in comfortably under 2.1/2 hours.

But do not turn up expecting to see the architecture of one of the great race circuits in the way that you do if you visit Reims. Go to Clermont and your enjoyment will be doubled if you do your research beforehand and pack your imagination. Know where to look and you will find the odd relic, the occasional slice of the past lurking here and there — but you will have to work at it.

To an extent, this is perhaps as it should be. The magnificence of Clermont never had anything to do with its facilities; indeed there were precious few, as you might expect from a track which was only ever used once a year and for the remaining 364 days was effectively a ring road around twin volcanic plugs. Go to Clermont today and you don’t need elegantly faded tribunes, or quietly crumbling control towers; go to Clermont, drive the track, marvel at the natural beauty of the circuit and imagine what it must have been like in a DFV-powered Formula One car.

“A lot of people used to wear open-faced helmets there so they could throw up as they went down the hills…” This frank and typically illuminating piece of information came from the late Denny Hulme, as quoted in Joe Saward’s World Atlas of Motor Racing. And it would seem he wasn’t joking. In 1969, DSJ’s race report in Motor Sport recalls Jochen Rindt having a particularly tough time: “The Austrian was suffering from sickness and diziness, thought to be brought on by the violent G-forces generated on the Clermont-Ferrand circuit.. He finally had to retire from the race when he began to get double-vision.” It is some measure of the man that he returned a year later and won.

Drive the circuit and it’s easy to see why Rindt’s constitution reacted so violently. Apart from a short stretch past the pits and another uphill section immediately after, the circuit has no straights worthy of the name. Right round the mountain, one corner flows into another with dizzying frequency around the five mile lap. It is truly daunting.

Though rumblings of a track in the hills around Clermont-Ferrand were heard as early as 1908, this circuit was the brainchild of Jean Auchataire, the local Fiat dealer, encouraged by Toto Roche, the man also responsible for Reims. According to the legendary French journalist Jabby Crombac, the man who has attended more Grands Prix than anyone else alive, Roche’s motives were not exactly pure.

“He was in favour of anything that took attention away from Le Mans. He backed the circuit at Clermont-Ferrand just to sock it to the authorities there.” Work began in May 1957 and was completed in time for the first meeting to be held the following July. The cost of rather more than 100 million Francs was paid by the local authority, topped up by contributions from car clubs, the town of Royat and the newly formed Societe de Circuit.

Andrew Frankel at Louis Rosier Clermont Ferrand memorial

Memorial to Louis Rosier, ace driver and local lad who died before work on the circuit began

The first race was held on July 27 with a three-hour sportscar race heading the bill. Crombac, Colin Chapman’s assistant team manager at the time was able to persuade the authorities to homologate a Lotus 11 for Innes Ireland, who duly walked away from the field, leading the Ferrari 250GTs of Olivier Gendebien and Maurice Trintignant to victory.

And for the next six years, Clermont-Ferrand hosted sports car and Formula Two races, while the Grand Prix fluctuated between Reims and Rouen. Stirling Moss won in the Cooper-Borgward in 1959, Jo Bonnier claiming the Six Hour race the following year in a Porsche RS60. Willy Mairesse won the following year aboard a 250GT SWB while Carlo Abarth took its successor, the 250GT0, to the flag in ’62. Lorenzo Bandini won in a Ferrari Testa Rossa in ’63 while the big F2 race the following year saw Denny Hulme lead home Jackie Stewart and Jack Brabham.

It wasn’t until 1965 that the French Grand Prix finally arrived. “I didn’t win it,” says Jackie Stewart today, “but it was one of the races that made people sit up and take notice of me.” The record books show why. It was the year in which Jim Clark won every Grand Prix he finished and this was the final championship outing of his Lotus 25. The BRM-borne Stewart qualified and finished second, 27sec behind Clark and over two minutes ahead of anyone else. “It was seen as an achievement because it was recognised as a real driver’s circuit.”

There were problems, however, both on and off the track. Back then, Clermont-Ferrand was a long way from anywhere and coaxing sufficient people through the gate was always a problem. And the financial ramifications of this were compounded by the expense of closing the roads for a meeting, which was colossal. This was no small kart track, and resources required to barrier and police all the access points stretched finances further than they usually cared to go. In addition, the on-track facilities were not what you’d expect, even in the mid-60s. Crombac remembers, “The pits were so small there was no room even for refuelling. All the teams, when they needed more fuel, had to leave the pits and go off to another area of the track, refuel and return. Not ideal…”

BMW rounds corner of Clermont Ferrand GP circuit

At the left-hander over the bridge as it is today

Cars round corner at bridge in 1970 French Grand Prix

Hill & Siffert in ’69; bridge is one of few surviving relics of old track

Even the surface of the track brought its own problems. Because of its location, there was (and remains) a vast amount of volcanic debris around the circuit. And while it was kept off the main track, it littered the verges and punished doubly anyone who stepped a little bit off line.

So far as the Grand Prix was concerned, that was it for another four years. The race returned to Reims for the last time in ’66, had one, ludicrous outing on the Bugatti circuit at Le Mans in ’67 and a final fling at Rouen in ’68 where the death of Jo Schlesser in the rain ended its career as a Grand Prix venue.

So, by 1969, Clermont-Ferrand seemed to have the stage to itself. Reims was too fast, Le Mans too boring and Rouen just too dangerous. But the honeymoon lasted only two years, enough for Stewart to win at last in his Matra in 1969 and for Rindt to score one of the last wins of his too-short life when he scorched from pole to victory in 1970. One who was there on both occasions and remembers them well is John Miles, now one of the reasons Lotus makes the best-handling cars in the world, then a relatively inexperienced works Lotus Grand Prix driver. He found the circuit outstandingly tricky. “You had to be so precise there; much more so than at other tracks. The roads were narrow and you had to stay on line. The problem was so many corners looked alike and I never spent enough time there to really get to know it. Like at the Nurburgring, it is those who are able to commit to the blind brows and the sequences of comers who are going to be quickest. You couldn’t afford even a confidence lift, particularly on the uphill sections but at the same time, if you did make a mistake, there was absolutely nowhere to go. All the corners flowed into each other and the real aces could recognise that, if they made a mistake at point A, by the time they’d reach point D, they were going to have a really big accident if they didn’t do something about it. I didn’t have that luxury.”

Then, in 1971, the writing appeared on the wall for Clermont-Ferrand and it said ‘Paul Ricard’. It was then that the eponymous pastis millionaire opened the most modem Grand Prix track in the world. Located at Le Castellet in the South of France it had all the facilities, glamour and access Clermont-Ferrand lacked. Clermont would see just one more Grand Prix.

BMW 3 series powerslides at Clermont Ferrand circuit

BMW 328Ci plays Formula 1 car at the exit of one of track’s 50 corners…

Emerson Fittipaldi powerslides his Lotus in the 1972 French Grand Prix

…and Emerson Fittipaldi doing it for real in 1972

The 1972 French Grand Prix is remembered among the long list of races Chris Amon should have won. Unlike the others, however, Anion reckons it was the greatest of his life. Driving the Matra MS120D, he flew around the 50 corners that comprise a lap here to qualify nearly a second quicker than anyone else. At the start he led comfortably from Hulme and Stewart with the rest of the field nowhere. And he was extending his lead when, at half distance, one of his tyres fell foul of the now notorious track debris. He crawled back to the pits, spent 50sec stationary and rejoined in ninth position, less than amused.

Why his fightback has not gained legendary status is a mystery to me. With almost no straight, overtaking was horrendous but by lap 35 of 38 he was fifth, having smashed the lap record before coming up behind Ronnie Peterson and Francois Cevert. DSJ, not known for handing out the plaudits too readily, takes up the story:

“In one lap, Amon disposed of Peterson and Cevert, passing them as if they were not there and on a circuit that is noted for its lack of passing places. It was fantastic and almost unbelievable. Not content with that he lopped four seconds a lap off Fittipaldis lead, but the race was one lap too short for the New Zealander.”

He finished third, behind Emerson and Stewart. But if he had cause to curse the rock strewn circuit, Helmut Marko had rather more. One such rock pierced his visor, blinding him in one eye and ending a promising career which included winning Le Mans in 1971 at an average speed that, to this day, has yet to be eclipsed.

Such distant memories. The circuit is all still there, some of it as a much smaller, permanent race track and rather more as the old public roads. It’s still fabulous to drive, still daunting. Still littered with volcanic detritus. But almost everything else has gone. The grandstand has been pulled down and the once packed paddocks are now just areas of wasteland. We found a little bridge that’s in the old photographs and mugged up lurid oversteer shots for the camera at the tighter corners on the circuit. You can’t do a full lap because of the barriers between the track and the road. What you can do is forget about the car, park up and climb up onto the banks. It’s a very quiet place and nothing but the wind will disturb your concentration. And as you stand there, you might just hear that V12 Matra engine, the greatest sound ever to emanate from a Grand Prix car and see Chris Amon, coming down the sweeps, always out of shape, always over the limit.

Jackie Stewart crosses the line to win the 1969 French Grand Prix

Jackie Stewart raises his arm as he wins in ’69

Grandstand at modern Clermont Ferrand circuit

The old pits straight, part of the new permanent circuit, now has a small and nasty grandstand

Now it is an entirely forgotten place. In 1972, just two years after the previous Grand Prix held there, a dozen of the drivers had never even heard of the circuit before going to race there. So you can imagine how its memory has stood the last 28 years. But you should still go. On many of the old circuits there were certain requirements needed before you could go fast. Monza needed horsepower, Monaco needed grip, the Nürburgring served best those who could forget about home, while Spa needed daredevils. You only needed one thing to win at Clermont-Ferrand and that was, very simply, to be the greatest driver of your day. Go there and you will see why.

A few extra photos....

Chris Amon Matra 1972. Shoulda Coulda Woulda

Jochen Rindt 1970

Jackie Ickx 1969

Facilities what facilities! March and BRM Paddock area 1970

Didnt get much better.... above McLaren in 1972

Jim Clark 1965

Helmut Marko BRM 1972

1965

Dave Walker Lotus 1972

John Surtees Ferrari 1965

* I started life with nothing, and still have most of it left

“Good drivers have dead flies on the side windows!” (Walter Röhrl)

* I married Miss Right. Just didn't know her first name was Always

- erwin greven

- Staff

- Posts: 20075

- Joined: 19 years ago

- Real Name: Erwin Greven

- Favourite Motorsport: Endurance Racing

- Favourite Racing Car: Lancia Delta 038 S4 Group B

- Favourite Driver: Ronnie Peterson

- Favourite Circuit: Nuerburgring Nordschleife

- Car(s) Currently Owned: Peugeot 206 SW Air-Line 3 2007

- Location: Stadskanaal, Groningen

- Contact:

The Story of the 1972 French GP

Brian Redman: "Mr. Fangio, how do you come so fast?" "More throttle, less brakes...."

- MonteCristo

- Moderator

- Posts: 10713

- Joined: 8 years ago

- Favourite Motorsport: Openwheel

- Favourite Racing Car: Tyrrell P34/Protos

- Favourite Driver: JV

- Favourite Circuit: Road America

- Location: Brisbane, Australia

Thanks

I'll keep an eye out for the other episodes.

Oscar Piastri in F1! Catch the fever! Vettel Hate Club. Life membership.

2012 GTP Non-Championship Champion | 2012 Guess the Kai-Star Half Marathon Time Champion | 2018 GTP Champion | 2019 GTP Champion

2012 GTP Non-Championship Champion | 2012 Guess the Kai-Star Half Marathon Time Champion | 2018 GTP Champion | 2019 GTP Champion

- Starling

- Bronze Member

- Posts: 187

- Joined: 2 years ago

- Real Name: Paola

- Favourite Motorsport: F1

- Favourite Driver: Ayrton Senna

- Favourite Circuit: Monza, Montecarlo

- Car(s) Currently Owned: Nissan Micra (vintage in 3 yrs)

Cheers Jim <3 Beautiful pics

Nada pode me separar do amor de Deus.

- Everso Biggyballies

- Legendary Member

- Posts: 49195

- Joined: 18 years ago

- Real Name: Chris

- Favourite Motorsport: Anything that goes left and right.

- Favourite Racing Car: Too Many to mention

- Favourite Driver: Kimi,Niki,Jim(none called Michael)

- Favourite Circuit: Nordschleife, Spa, Mt Panorama.

- Car(s) Currently Owned: Audi SQ5 3.0L V6 TwinTurbo

- Location: Just moved 3 klms further away so now 11 klms from Albert Park, Melbourne.

On this Day 29th June 1980

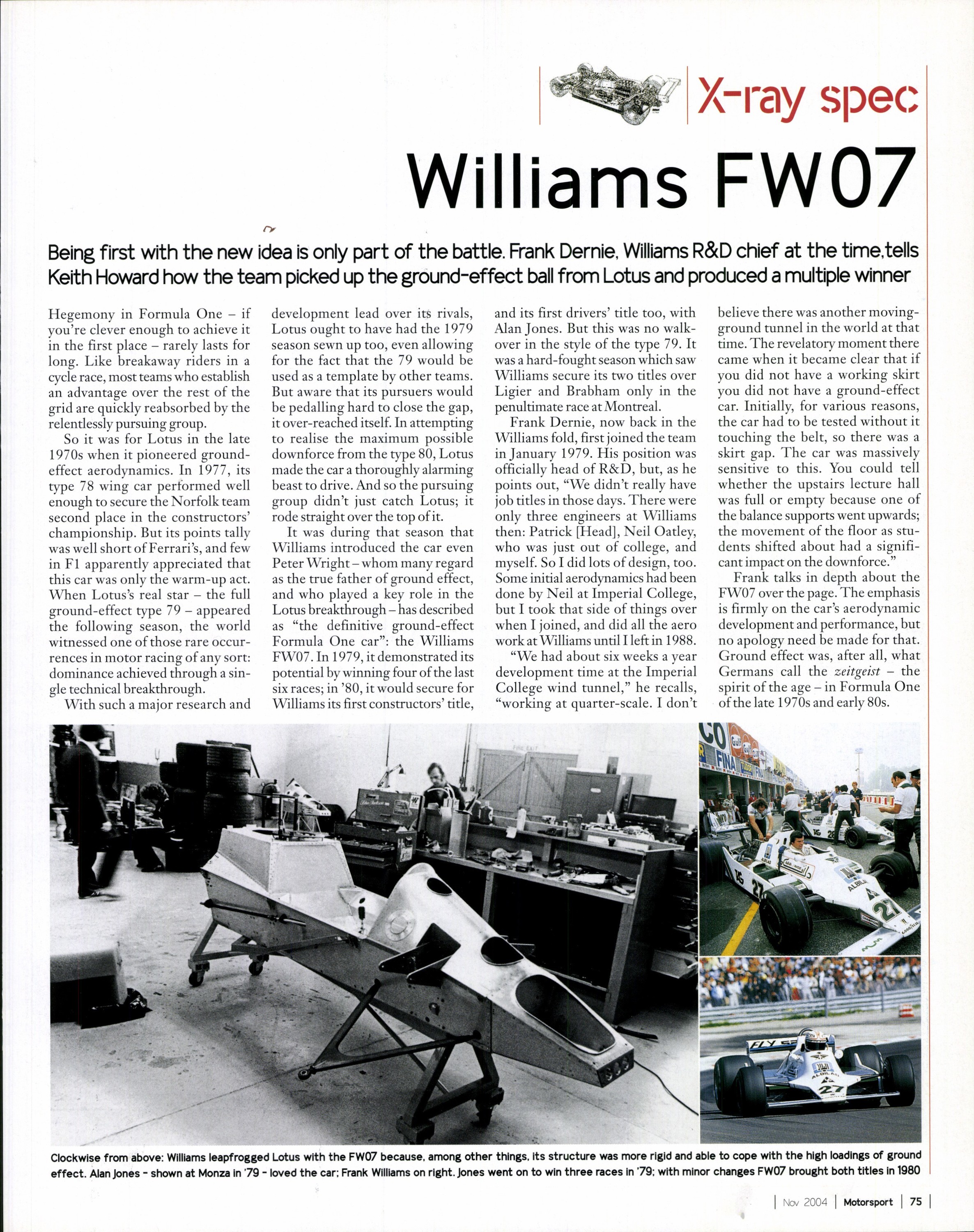

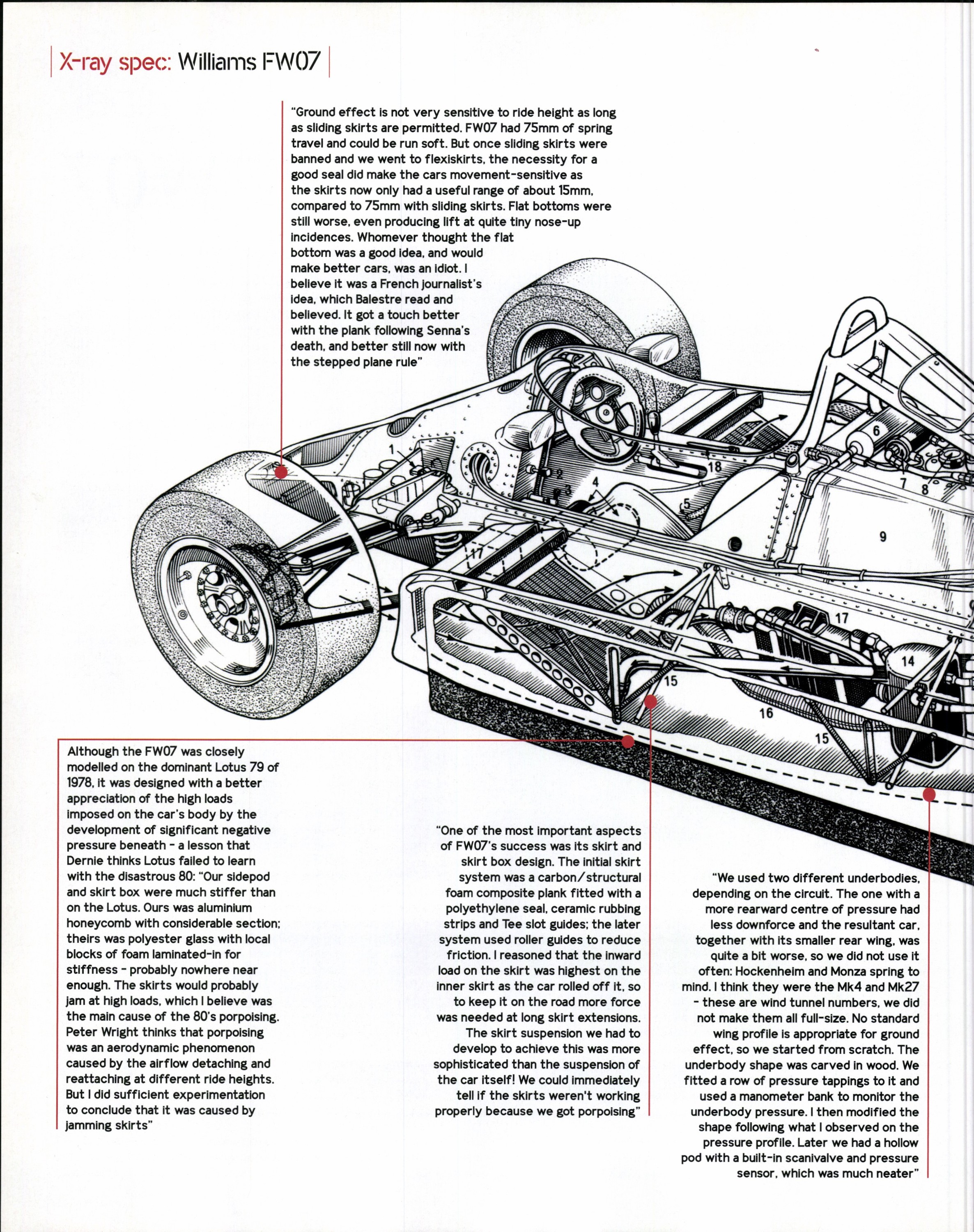

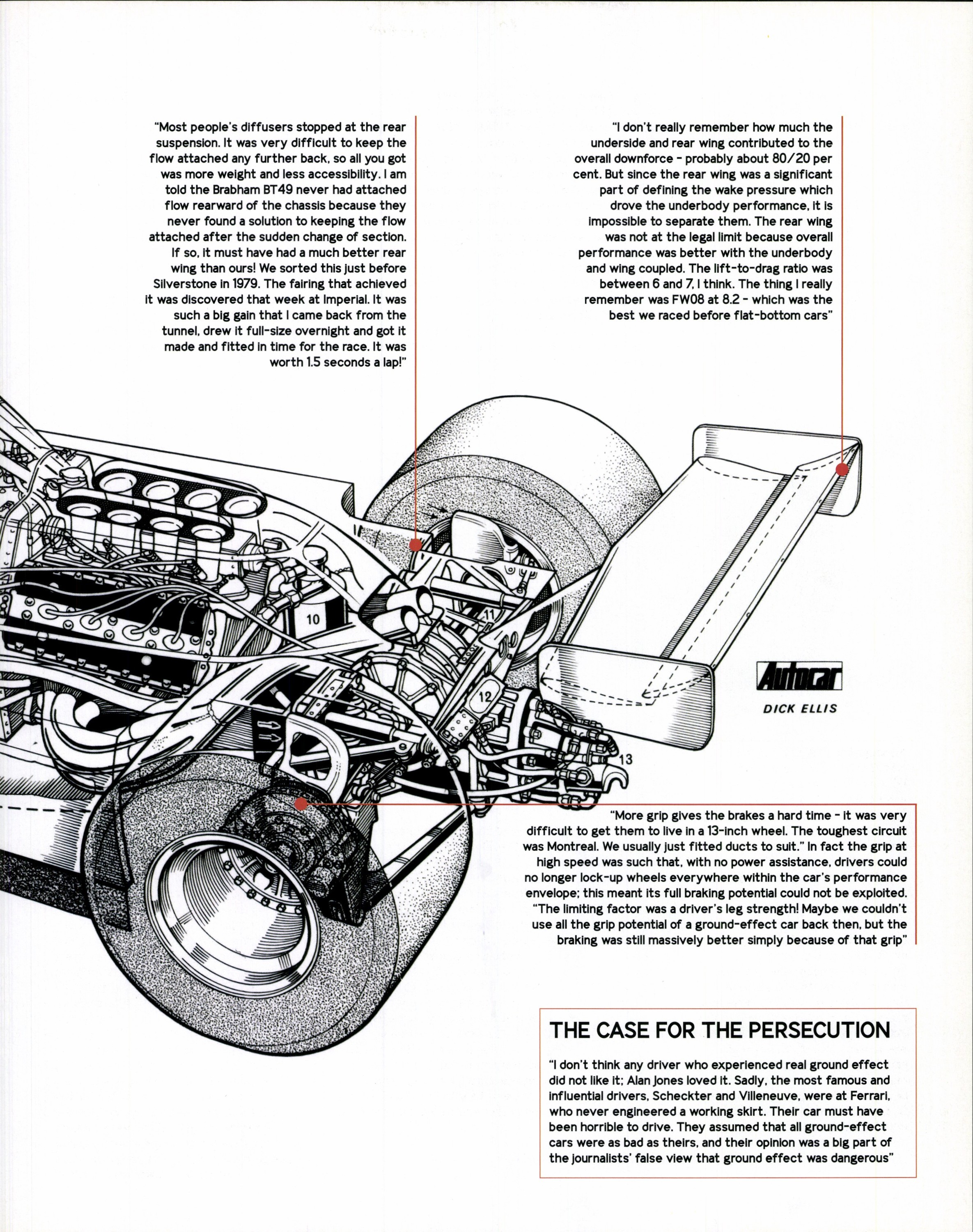

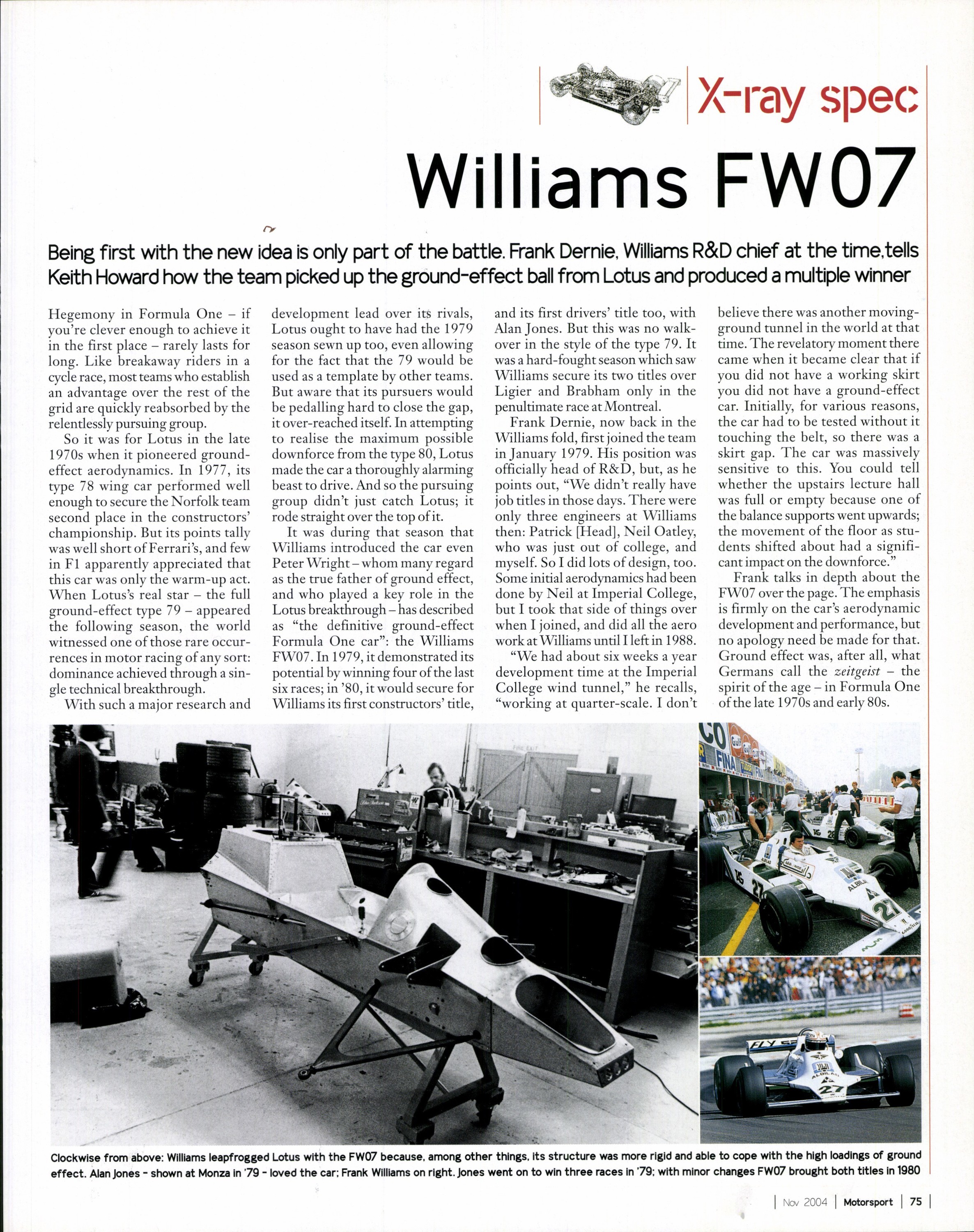

Alan Jones won the French Grand Prix in a Williams FW07.

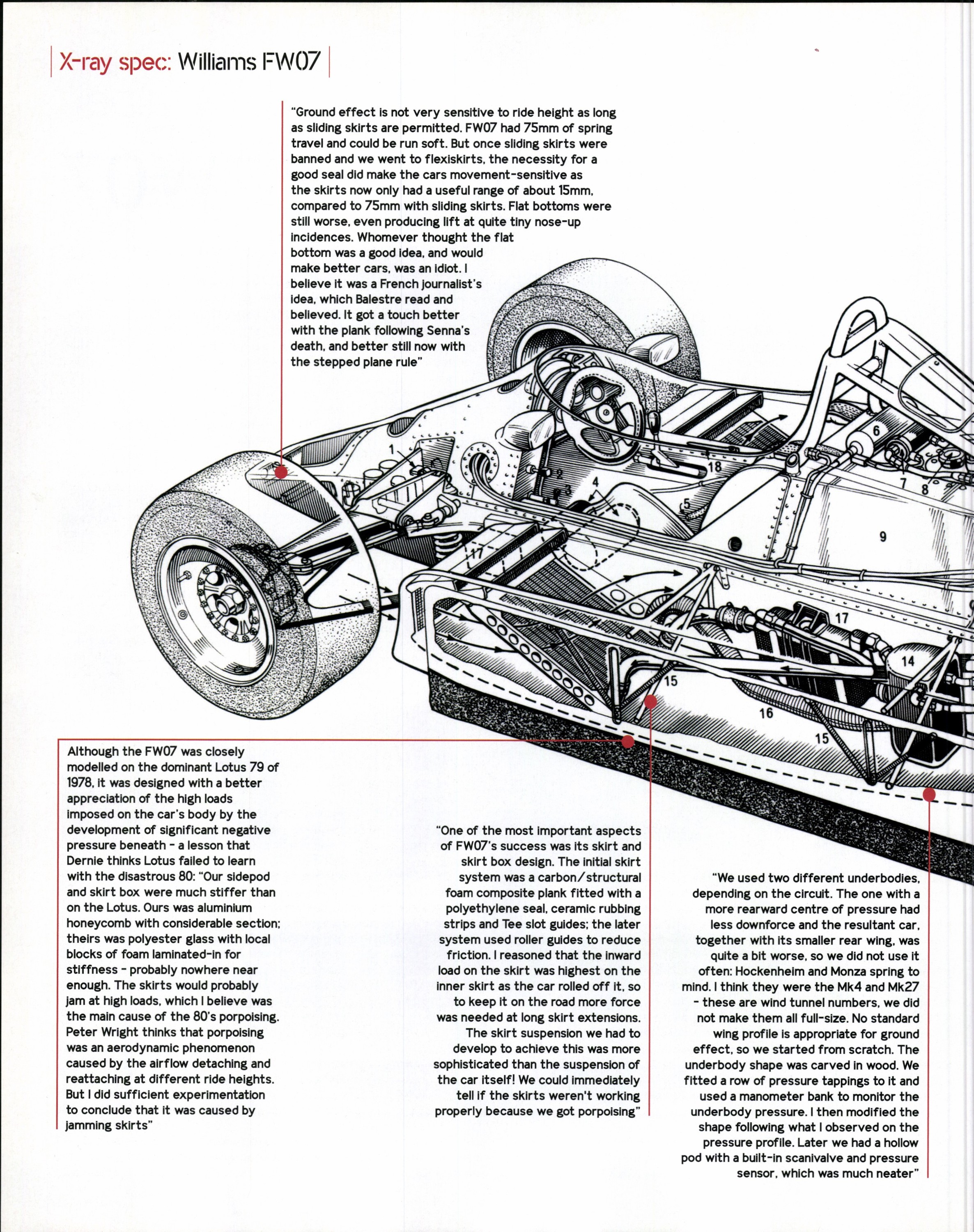

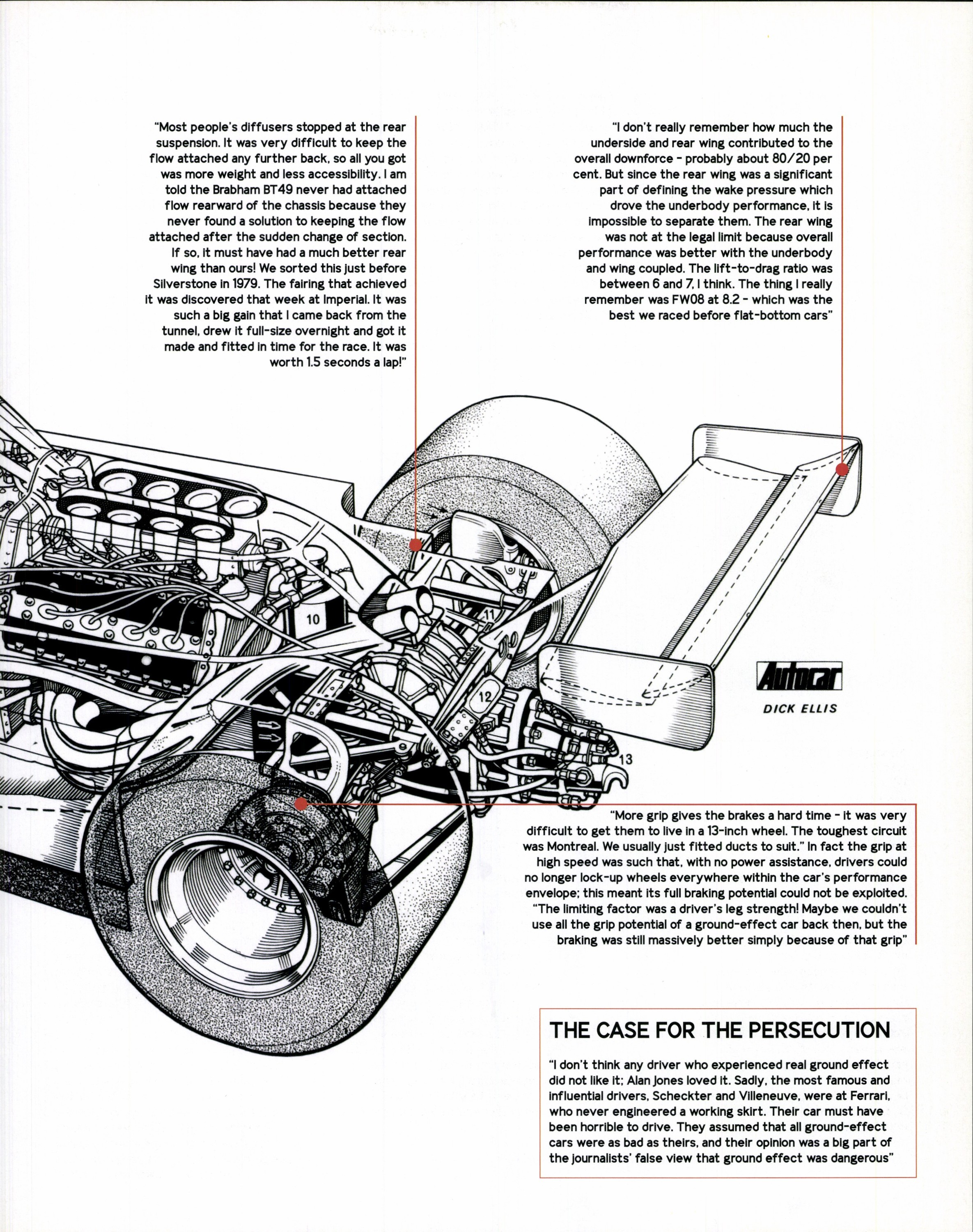

Again I am not posting about the event, but the car he drove. A turning point for Formula 1 and a car that was not only beautiful but absolute state of the art....even Peter Wright, whom many regard as the true father of ground effect, and who played a key role in the Lotus breakthrough, has described the FW07 as "the definitive ground-effect Formula 1 car".

I talk of beauty.... and bear in mind this was nearly 45 years ago, I was a testosterone charged youth and we had never even heard of the phrase "Politically correct". I look back a little embarrassed to admit it but my (male) friends and I used to score young ladies looks by relating to a race car.... a particularly attractive trim and well proportioned girl would be an FW07.... perhaps a more overweight girl would be a McLaren M10B F5000 car (with big fuel bag tanks in the sidepods) or a Ligier JS5. An Ensign was basically not attractive.

Anyway moving on from that, Alan Jones broke French hearts on this day in 1980, as he swept to victory in the French Grand Prix, where hopes of a home win had been high as five of the top seven grid slots were taken by French drivers.

In 1979, it had demonstrated its potential by winning four of the last six races; in '80, it would secure for Williams its first constructors' title, and its first drivers' title too, with Alan Jones. But this was no walkover in the style of the type 79. It was a hard-fought season which saw Williams secure its two titles over Ligier and Brabham only in the penultimate race at Montreal.

As an aside the aerodynamic effect generated around two tonnes of downforce at about 300km/h. B-i-i-i-i-g numbers back then.

Fortunately I get to see one every year at Phillip Island as one of the original Jones cars is owned by an Aussie. FW07/04 for the nerds.

Anyway this article from Motor Sport archives .

X-Ray Specs Williams FW07

Some more pics.

Alan Jones won the French Grand Prix in a Williams FW07.

Again I am not posting about the event, but the car he drove. A turning point for Formula 1 and a car that was not only beautiful but absolute state of the art....even Peter Wright, whom many regard as the true father of ground effect, and who played a key role in the Lotus breakthrough, has described the FW07 as "the definitive ground-effect Formula 1 car".

I talk of beauty.... and bear in mind this was nearly 45 years ago, I was a testosterone charged youth and we had never even heard of the phrase "Politically correct". I look back a little embarrassed to admit it but my (male) friends and I used to score young ladies looks by relating to a race car.... a particularly attractive trim and well proportioned girl would be an FW07.... perhaps a more overweight girl would be a McLaren M10B F5000 car (with big fuel bag tanks in the sidepods) or a Ligier JS5. An Ensign was basically not attractive.

Anyway moving on from that, Alan Jones broke French hearts on this day in 1980, as he swept to victory in the French Grand Prix, where hopes of a home win had been high as five of the top seven grid slots were taken by French drivers.

In 1979, it had demonstrated its potential by winning four of the last six races; in '80, it would secure for Williams its first constructors' title, and its first drivers' title too, with Alan Jones. But this was no walkover in the style of the type 79. It was a hard-fought season which saw Williams secure its two titles over Ligier and Brabham only in the penultimate race at Montreal.

As an aside the aerodynamic effect generated around two tonnes of downforce at about 300km/h. B-i-i-i-i-g numbers back then.

Fortunately I get to see one every year at Phillip Island as one of the original Jones cars is owned by an Aussie. FW07/04 for the nerds.

Anyway this article from Motor Sport archives .

X-Ray Specs Williams FW07

Some more pics.

* I started life with nothing, and still have most of it left

“Good drivers have dead flies on the side windows!” (Walter Röhrl)

* I married Miss Right. Just didn't know her first name was Always

- Michael Ferner

- Senior Member

- Posts: 3531

- Joined: 7 years ago

- Real Name: Michael Ferner

- Favourite Racing Car: Miller '122', McLaren M23

- Favourite Driver: Billy Winn, Bruce McLaren

- Car(s) Currently Owned: None

- Location: Bitburg, Germany

Hmm. Being in a nitpicky mode, but commemorating a win by an FW07B, but showing (predominantly) picturers of the 1979 version is... weird.Everso Biggyballies wrote: ↑1 year ago On this Day 29th June 1980

Alan Jones won the French Grand Prix in a Williams FW07.

Again I am not posting about the event, but the car he drove.

Maybe because I am an old fart, but to me the two cars look distinctively different!

2023 'Guess The Pole' Points & Accuracy Champion

If you don't vote now against fascism, you may never have that chance again...

If you don't vote now against fascism, you may never have that chance again...

Ceterum censeo interruptiones essent delendam.

- Everso Biggyballies

- Legendary Member

- Posts: 49195

- Joined: 18 years ago

- Real Name: Chris

- Favourite Motorsport: Anything that goes left and right.

- Favourite Racing Car: Too Many to mention

- Favourite Driver: Kimi,Niki,Jim(none called Michael)

- Favourite Circuit: Nordschleife, Spa, Mt Panorama.

- Car(s) Currently Owned: Audi SQ5 3.0L V6 TwinTurbo

- Location: Just moved 3 klms further away so now 11 klms from Albert Park, Melbourne.

Fair call, they are quite different in profile, the 7 having a more pronounced fin at the rear of the sidepod with the 7B a more sculpted look. And bar Argentina Alan did use a 7B throughout 1980.Michael Ferner wrote: ↑1 year agoHmm. Being in a nitpicky mode, but commemorating a win by an FW07B, but showing (predominantly) picturers of the 1979 version is... weird.Everso Biggyballies wrote: ↑1 year ago On this Day 29th June 1980

Alan Jones won the French Grand Prix in a Williams FW07.

Again I am not posting about the event, but the car he drove.

Maybe because I am an old fart, but to me the two cars look distinctively different!

Both the 7 and the 7B were both great cars though, (the 7B is probably a cleaner looking and tidier car.)

* I started life with nothing, and still have most of it left

“Good drivers have dead flies on the side windows!” (Walter Röhrl)

* I married Miss Right. Just didn't know her first name was Always

- Everso Biggyballies

- Legendary Member

- Posts: 49195

- Joined: 18 years ago

- Real Name: Chris

- Favourite Motorsport: Anything that goes left and right.

- Favourite Racing Car: Too Many to mention

- Favourite Driver: Kimi,Niki,Jim(none called Michael)

- Favourite Circuit: Nordschleife, Spa, Mt Panorama.

- Car(s) Currently Owned: Audi SQ5 3.0L V6 TwinTurbo

- Location: Just moved 3 klms further away so now 11 klms from Albert Park, Melbourne.

On this day 6th July 1958...

....We lost Luigi Musso in a crash at the French GP

Musso had vied with Eugenio Castellotti for the mantle of becoming Italy's top driver following Ascari's death in 1955.

Musso's ambition and passion to be the most successful driver at Ferrari led him and other drivers in the team to disregard common sense and take more chances than perhaps they should.

Castellotti (No24) and Musso on the grid at Monza ahead of the 1956 Grand Prix

This article from Motor Sport archives by Chris Nixon outlines these rivalries, particularly that between Musso and Castellotti and their at times lack of common sense such was the rivalry in their brief and tragic careers.

....We lost Luigi Musso in a crash at the French GP

Musso had vied with Eugenio Castellotti for the mantle of becoming Italy's top driver following Ascari's death in 1955.

Musso's ambition and passion to be the most successful driver at Ferrari led him and other drivers in the team to disregard common sense and take more chances than perhaps they should.

Castellotti (No24) and Musso on the grid at Monza ahead of the 1956 Grand Prix

This article from Motor Sport archives by Chris Nixon outlines these rivalries, particularly that between Musso and Castellotti and their at times lack of common sense such was the rivalry in their brief and tragic careers.

https://www.motorsportmagazine.com/arch ... ung-bloodsThe battle to be Italy's No1 driver: Musso and Castellotti's 1950s Ferrari rivalry

“Listen lads, you won’t have to work too hard to win this race. At the start, I’ll set the rhythm. You follow me, and you won’t shred your tyres. Ten laps from the end, I’ll pull over, and then you two, between you, can decide who wins. Even if I come third or fourth, I’m still World Champion.”

The ‘lads’ were Luigi Musso and Eugenio Castellotti, and that very sensible advice came from their Ferrari team-mate, Juan Manuel Fangio. The race was the 1956 Gran Premio d’Europa at Monza and the two Italians – serious rivals, never friends – were both determined to win their own Grand Prix. Ignoring the Old Man’s advice, they went like bats out of hell from the fall of the flag and, as he knew they would, shredded their tyres inside five laps. Fangio won his fourth Championship and ‘the lads’ finished the race in the pits, out of the results and not speaking to each other.

The chances of them heeding the advice of even the great Fangio were nil, for since the death of the great Alberto Ascari the year before they had been jockeying for position as Italy’s number one. Neither possessed Alberto’s remarkable skills, but they were pretty damn quick and each had a large following.

Their rivalry dates from 1953, when they began to make a name for themselves, and was undoubtedly intensified by the centuries-old antagonism between the cities of their birth.

“Musso is Rome and Castellotti is Milan!” recalls Romolo Tavoni, forcefully. He saw both men at the height of their careers and was in the unenviable position of being Ferrari team manager at the time of their deaths.

Luigi Musso at Monza, 1957

Luigi was regarded as the noble Roman, handsome and sophisticated but lazy. One of five children, he was born to wealth and privilege in 1924, and began racing in 1950 with a 750c Giaur sportscar. One of the first people he met on the circuits was Maria Teresa de Filippis, a very pretty young lady who was also racing a Giaur and causing something of a stir in the very male bastion of Italian motor racing. They fell in love, which brought problems because Luigi was married with two small children.

“I was engaged to Luigi for three years while we waited for the church to annul his marriage,” recalls Maria Teresa. “Meanwhile we went racing together all over Italy. We used to bet on our races and one bet was a gold watch for the one who crashed last at a hillclimb. Luigi crashed first, so I got the watch. He was a great guy and a great help to me in my career.”

Musso did not exactly set the world on fire in his first three seasons, finishing second seven times. At the end of 1952 he and Maria Teresa decided that they had had enough of waiting for his marriage to be annulled. They went their separate ways for 1953, he with a 2-litre Maserati and she with an 1100cc OSCA.

Now things began to happen. Luigi finished a creditable 11th in the Targa Florio and scored a hat-trick of road-race wins, which brought him to the attention of Maserati, and in the Italian GP he shared a works car with Sergio Mantovani. They finished seventh. Two more victories in his own car won him the 2-litre Italian Sportscar Championship that year and Maserati promptly signed him up for 1954.

He and Giletti drove their 2-litre A6GCS to sixth overall in the Buenos Aires 1000Km. Back home he was fourth in the Tour of Sicily, a remarkable third in his very first Mille Miglia, won the Naples sportscars GP and finished second overall in the Targa Florio. Then he scored his first F1 win at Pescara, in a 250F. He finished the season with a fine third in the Tourist Trophy in a 2-litre Maserati and an even better second in the Spanish GP, behind Mike Hawthorn’s Ferrari.

In 1955 he was third in the Tour of Sicily; second at Naples, Bordeaux and Syracuse and then won the Supercortemaggiore 1000km at Monza, sharing a Maserati with Jean Behra.

The next year, Musso joined Scuderia Ferrari, as did Juan Fangio, Peter Collins and Eugenio Castellotti. In practice for their first race as team-mates the Argentine GP Luigi and Eugenio recorded exactly the same time in their Lancia-Ferraris. Musso did slightly better in the race, however, for Castellotti retired, whereas Fangio took over Luigi’s car and drove on to win. Thus Luigi was co-credited with what was to be his one and only championship victory.

At Maranello ahead of the 1956 Mille Miglia From left: Musso, Enzo Ferrari, Castellotti and Collins

In May he rolled his Ferrari on the third lap of the Nürburgring 1000Km, broke his arm, and was hors de combat until the Italian GP. This was annoying, but gave him plenty of time for gambling. “Musso loved racing, but even more he loved to gamble,” recalls Tavoni.

Musso’s enforced layoff gives us a convenient break in which to look at the career of his great rival. Proud and provincial, Eugenio Castellotti was swarthily handsome and also rather short, frequently wearing shoes with built-up heels.

“He was a very nice young man,” Tavoni says, “interested only in cars, racing and girls. He was born in 1930 in Lodi, near Milan, and his father was a rich landowner who died when he was 12 years old.”

In fact his father was not married to his mother, Angela, but he left her a large sum of money in his will, so when in 1951 Eugenio decided to go motor racing, he was able to buy a 2-litre Ferrari 166. In the Tour of Sicily he retired, but then finished sixth in class in the Mille Miglia. How easy it was in those days! Castellotti was not yet 21, had zero racing experience, yet began his career in two of the world’s greatest road races.

Castellotti and companions in 1955, ahead of the Mille Miglia

Next season he acquired a 2.7-litre 225S Ferrari and took fifth place in the Tour of Sicily. He then won the Pescara Gold Cup with the 166. The Monaco GP was for sportscars that year and Eugenio finished a fine second in the 225S, then won the Portuguese GP.

In 1953 success in road races brought him a Lancia contract, but the team failed dismally in the Nürburgring 1000Km and he did not get a drive. However, he made Lancia’s D23 perform impressively on the hills, and became Italian Mountain Champion. Finally, he went to Mexico for the Carrera PanAmericana, where Lancia swept to a tremendous 1,2,3 victory (Fangio, Taruffi, Castellotti).

Early in 1954 Lancia announced that it was going into Formula One. Ascari and Villoresi were signed to lead the team, with Castellotti as the junior driver. Unfortunately, the D50 GP car wasn’t ready until the very end of the season and Eugenio did not race it. He had a pretty disappointing year in Lancia’s sportscars, too, retiring at Sebring and in the Mille Miglia and Targa Florio. He won five climbs, though, and was Mountain Champion for the second year running.

He finally got his hands on the D50 Lancia in the 1955 Argentine GP. He retired there, but finished fourth in Turin and second at Pau, as he did in the Monaco GP, when while catching the Ferrari of the ultimate winner, Maurice Trintignant, he spun his chance away in the final laps.

Lancia then decided to withdraw from sportscar racing to concentrate on F1, so Eugenio raced Ferraris in endurance events. He put up bravura performances in the Mille Miglia and at Le Mans with the 4.4-litre 121LM, leading both races from the outset, but overtaxing his car in the process.

A few days after the Monaco Grand Prix, Castellotti was at Monza, practising a works 750 Monza for the Supercortemaggiore 1000Km, when Ascari arrived unannounced and asked if he could do a few laps. He had always been fastidious about driving in his own racing gear slacks, shirt, helmet and goggles but he had brought none of these with him, so he borrowed the latter two items from an astonished Castellotti and set off. A couple of laps later he crashed inexplicably and was killed.

This tragedy coincided with the collapse of the Lancia company, with the result that all the GP cars and equipment were handed over to Scuderia Ferrari. Castellotti put in one last valiant effort for the firm at Spa. He took pole position in practice with a new lap record, but in the Grand Prix the D50 expired after 17 laps, when in third place. He then went with the Lancias to Ferrari and scored a fighting third place in the Italian GP (driving a Ferrari Squalo 555) behind the Mercedes of Fangio and Moss.

Musso joined Castellotti at Ferrari for 1956, but it was the latter who got the better deal in endurance events, being paired with Fangio in most of them. The Master and the youngster got on well and won the Sebring 12 Hours in an 860 Monza, ahead of Musso and Schell in a similar car.

Castellotti needed no help at all in the Mille Miglia, however. Driving solo, he raced to a brilliant victory through pouring rain for almost the entire 1000 miles. Musso finished third, half-an-hour behind his rival.

Luigi finished second in the Syracuse GP and Castellotti was second to Peter Collins in the French GP, all driving what were now known as Lancia-Ferraris. Eugenio and Fangio (860 Monza) were second in the 1000Km at the ‘Ring and third in the Supercortemaggiore 1000Km at Monza in a 2-litre Ferrari. Eugenio then won the Rouen GP for sportscars.

The 1956 Italian GP was a remarkable event for two reasons. Firstly it was a tremendous race and secondly Peter Collins gave his car to Fangio, thus ensuring the maestro won his fourth title, despite the fact that Peter had a slim chance of winning himself.