Stefan Bellof: One move too many

Stefan Bellof was the greatest lost talent of his generation. He had time and skill on his side and a Ferrari contract in his pocket. But he couldn't stop himself, says Mark Hughes

“When he joined the factory Porsche team it was funny. All the other drivers were… not old, but about the age that seemed to be correct for factory drivers. Then he came in like a hurricane, this young guy, and just went about things absolutely in his own way, not like an employee. And went faster than them all.”

These are the words of Angelica Langner remembering her boyfriend, Stefan Bellof. They capture perfectly the free spirit and startling talent. If the sport were not so cruel, they’d be spoken with him sitting alongside her, each in their early 40s, happy in the glow of his recent retirement from a glittering career peppered with world titles. There might even be a card of congratulation from the only contemporary worthy of mention in the same breath, Ayrton Senna. And Stefan would be laughing that unmistakable raucous laugh.

But – ever the last man to lift, the driver who would invent passing places that were invisible to others, the endearing extrovert who wallowed in the enormity of his talent – Bellof’s hand reached out to that of fate. Motor racing lost a giant on 1 September 1985 at Eau Rouge, as Stefan tried one outrageous move too many.

“He just needed someone to control him a little bit more,” says Derek Bell, his driving partner at Porsche. “He had an incredible talent but he wasn’t controlled by anyone at a time in his career when he needed it. I was surprised that Ken Tyrrell didn’t, but maybe F1 teams don’t want to control drivers, maybe they like this wild attitude because it gives better lap times. I was even more surprised that Porsche didn’t jump on him from a height.

“At Nurburgring in ’83 he’d put it on pole, and by the time he came to do his second stint, we were leading comfortably. Yet on his first lap out he knocked about four seconds off the lap record and I remember walking up to the Porsche and saying, ‘Why don’t we give him an Easy sign?’ and they just looked at me and laughed, like ‘the boy’s having a good time.’ Next lap he put the thing on its roof.”

No one ever could say no to Stefan. The irrepressible charm and humour did the trick every time. In November 1980 German motor sport journalist Reine Braun was working in his office when the phone rang. ‘Hello, I’m Stefan Bellof,’ said the voice, ‘and Walter Lechner tells me you are the guy who can help me get faster cars and find some money. You are the right man for me.’

“I didn’t even get time to say, ‘I don’t have time’,” says Braun. “He didn’t say, ‘Can I come and see you?’ The door just opened and he was in the office. I said, ‘I must work at the moment’. He said, ‘Yes, I’ll wait.’ He waited one hour, two hours and still he wouldn’t go away. So in the end I had to talk to him. I said that I had a problem with helping him because just a few months earlier Hans Georg Burger, a driver with whom I was very friendly, had been killed. I showed Stefan pictures of Hans Georg and said, ‘Do you want a nice life or do you want your story to end like this?’ He replied, ‘I will have a nice life and I will race. And you must help me.’

“I spoke with my wife and told her I wasn’t sure I could do this. And Stefan comes everyday. And if he wasn’t visiting, he was phoning, saying, ‘This is what we could do now, here’s a number of someone who might give us money.’ Eventually I said, ‘Okay, I surrender, I will do it’ It was the best decision I ever made in my life. The guy was fantastic. Not just in the car and I really believe he was on the same level as Senna or Schumacher but out of it. He was a wonderful human being. Warm and so funny. You missed a lot if you didn’t know him.”

The CV Bellof left on Braun’s desk was already impressive. He was a multiple title winner in German karting – like his older brother Georg – and in 1980 he had the distinction of being national champion in karting and Formula Ford. He achieved the latter with Walter Lechner Racing, a partnership organised by Georg.

The elder Bellof had got as far as European F3 in 1979. When he looked at Stefan he saw a whirlwind of talent, drive and charisma that was never going to be contained by a conventional career. Having established Stefan in cars, the quieter, less thrusting Georg defined a Y in their hitherto interlinked paths and retired from the sport. He would devote himself to dentistry and leave Stefan to destiny.

It can’t have been an easy choice. They had started out together. “We had a family coachwork business,” he says, “and in 1962, when Stefan was five and I was six, our father bought us a Goggomobil which we drove on the grounds of the garage. We were always driving cars and trucks and in 1972 father took us up to Oppanrodt, the local kart track.” So it began.

Georg made another vital link for Stefan too with Angelica. “I worked for their father,” she says, “but I didn’t know Stefan. I was at a disco in 1976 and Georg introduced us. He was nice, but he was too much like a little boy for me, I thought. All the time laughing and making jokes. I resisted for about six months but he kept trying until I agreed I would go out with him. We split up a couple of times until we realised we needed each other.

“He had this lovely joy of life, an acceptance of it and a vitality but on the other side he was very sensitive. He was a man you could never forget”

In time, Angelica’s family became Stefan’s. It was almost as if he was deliberately trying to distance himself from his own once his car racing career began. “He once said, ‘I don’t want my father to pay for the racing because then I don’t have to say thank you,’” says Angelica. The desire for independence was strong.

Lechner: “By the time I was running him, his father didn’t support him financially so much as morally. But Stefan would keep him out. If he tried to say something about the car or whatever, Stefan would say, ‘Here’s a coffee and a sandwich, just watch.”

“He liked his mum and dad,” continues Angelica, “but his life really was going in a different way to theirs. Maybe I was his family.”

In 1981, as well as winning the German ‘International’ FF1600 Championship and a few Super Vee races, entered by Lechner, Bellof made his F3 debut “It was with Bertram Schafer,” says Braun. “I told Stefan to behave properly because it was initially a one-off race and Bertram is a very serious, no-nonsense man.” Cue Bellof, all mock seriousness, introducing himself to a bemused Schafer: “Hello, I’m Stefan. Where’s the car?” He was on pole by two seconds at the end of qualifying. In the race, he went off at the first corner, rejoined at the back, charged through to second, less than 1 sec behind the winner.

“He was immediately quicker than Frank Jelinski, the reigning champion” says Schafer. “He was something special. Straightaway he fought with anyone — he had no respect of reputations. And he beat them. Straightaway.

“But he wouldn’t listen to advice, wouldn’t take help from outside. He couldn’t wait. That was part of him. He was very self-contained. That and jokes and bullshit from morning to evening is how I remember him.”

Monitoring his progress, at Braun’s behest, was BMW Competitions Manager, Dieter Stappert “I’d been at an ONS prize-giving,” he recalls, “and a guy was called up who’d won some kart championship and I was struck by the way he walked up to accept the trophy. He was grinning from ear to ear but seemed shy, too. It was a strange mix of shy and confident. I just liked the guy straight away. When Reine started telling me about this driver I realised it was the guy I’d seen at the prize-giving. I did what I could to help, even though Manfred Winkelhock and Gerhard Berger were getting our official support.

“Stefan reminded me a lot of Jochen Rindt. ‘How much does the world cost?’ is the phrase we have in Germany. They both had no respect for any reputations or conventions and they both had absolutely incredible reflexes.”

The German Maurer F2 team had BMW engines. Stefan got a call from Willi Maurer at the end of ’81. He should go to Paul Ricard for a test. Georg, who accompanied him, says: “Their regular driver was Beppe Gabbiani, and even though Stefan had never driven an F2 car before in his life, he went quicker than Beppe.” Done deal.

Bellof made his F2 debut in the opening round of the ’82 series, at Silverstone. And won it. Amusingly, this came six months after being excluded from the Brands Hatch Formula Ford Festival for driving ‘too aggressively.’ At the next F2 round, Hockenheim, Bellof did more than win — he destroyed the field. Up on the podium with him, Braun couldn’t hold back the tears.

Thereafter the Maurer’s reliability fell away and Bellof scored no further successes. He did complete a startling opening lap of the Nordschleife, though, setting a lap record from a standing start, passing Stefan Johansson in an outrageous manoeuvre along the way, immediately after the Pflanzgarten jump.

Braun: “Johansson said to a friend of Stefan’s afterwards, ‘Tell that crazy German you never try to pass anyone at that place.’ Stefan always had a special thing about overtaking.”

Alongside his continued F2 programme in ’83, Bellof joined the factory Porsche team in the World Endurance Championship. He and Bell won three times and some of his pole laps redefined Gp C driving. “The possibility of what could be done with a 956 only became clear when Stefan got into one,” says Lechner. “It was like climbing a mountain making it go really quick, because its ground effect meant unless you really pushed the car it just understeered. Logic would say you needed to lift off but if you stayed hard on the throttle it would stick to the track. He realised this immediately and the established guys — Ickx, Mass, Stuck, Wollek — were left behind.”

In 1984 he became World Endurance Champion for the team, if endurance can be applied to a series of spellbinding on-the-edge stints. “He wasn’t a sportscar driver,” says former Maurer mechanic Ian Harrison, “he was born for F1. Flat out from lights to flag.”

Formula One came in a hurry. He was called up in October ’83 by McLaren to attend a young driver test at Silverstone — in company with Senna and Martin Brundle. It was the famous occasion on which Senna kept his foot in to complete the lap even as the engine was destroying itself, then negotiated a second run denied to the others. It demonstrated the Brazilian’s all-encompassing approach. Bellof, by comparison, confined his efforts to the cockpit. Even had he lived out his natural career it’s doubtful whether he would have had the complete answer to Senna regardless of his similar talent.

“I think watching him and Senna develop together would have been very interesting,” says Lechner. “They were at about the same level, I think, but it’s true that Stefan was not all that bothered about details. They had very different approaches.”

“Actually their sensibilities were quite similar,” says Angelica. “It’s just that Ayrton’s was focused inward and Stefan was far more outgoing. They were actually quite friendly toward each other.” They’d met long before F1 in the karting world championship.

The test itself was fairly inconclusive, other than proving all three F1 aspirants were impressively quick — they all comfortably beat John Watson’s target time. Bellof and Brundle — both consigned to a DFV after Senna had blown the faster DFY — recorded 1min 14.7sec. This was 0.4sec off Senna’s first run, which was about the difference the more powerful engine would have made. Remember also that, unlike the others, Senna already had F1 experience by this stage — he’d tested for Williams earlier in the year.

It was Brundle’s first meeting with Bellof, a man he’d get to know well over the next two years as they were destined to be team-mates at Tyrrell.

“We didn’t say much to each other that day,” recalls Martin. “His English wasn’t very special and my German certainly wasn’t.” The McLaren run helped both drivers to perform devastating tests for Tyrrell later in the year, securing their drives there for ’84.

“There was a bit of tension at Tyrrell because I think Stefan expected to blow my doors off and he didn’t, really,” continues Brundle. “I was on a real high at that time, I was really on it, I had this supreme confidence that there was nothing to F1. It was nip and tuck between the two of us most of the time. But he did have a fantastic talent. He’d always be the last to brake, and he’d get into extraordinary situations and somehow get away with it. He was totally fearless. Way too brave, really. We’d be coming through the pack together and I’d see him pull off some incredible overtaking moves.”

It was never seen to better effect than at Monaco that year. Driving the only naturally-aspirated car in a field of turbos (Brundle hadn’t qualified), Bellof qualified on the back row, but in the rain of race day he was mesmerising. He began overtaking in impossible places — into the left-hander before the swimming pool, into Loews. He even took to the Mirabeau pavement to pass Rene Amoux’s Ferrari. Soon he was in third place closing on Senna’s Toleman, who in turn was catching the McLaren of race leader Prost He had the advantage of normally-aspirated throttle response, sure. But he was also 200bhp down. The race was called prematurely when the rain became especially severe.

“Everyone says if the race had lasted five laps longer Senna would have won,” says Stappert. “All I can say is, if it had been seven laps longer, Bellof would have caught Senna. Knowing them both, though, I think it’s fair to say the most likely outcome would have been them both going off fighting for the lead.”

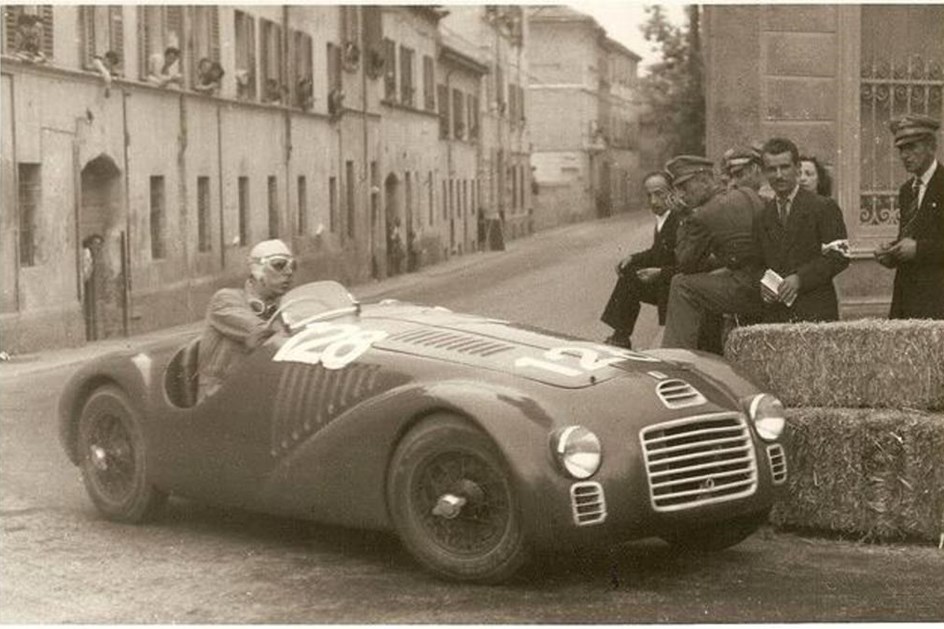

Though he was angry at the outcome, Bellof’s performance in that race — his sixth grand prix — had caught the eye of Enzo Ferrari. ‘They wanted him for ’85,” says Georg, “but they couldn’t get Arnoux out of his contract. So for the next year or so they negotiated for ’86. Before he died, it had all been agreed: he was going to Ferrari for ’86, alongside Michele Alboreto.”

With his future seemingly assured, he wasn’t unduly concerned about embarking on a second year with Tyrrell — which wouldn’t even have a turbo ready for him until the middle of the season. In order to devote more time to F1, he transferred from the factory Porsche team to the privateer outfit of Walter Brun — partly as a sop to Ken Tyrrell who didn’t want him to be doing sportscars at all, but who couldn’t say no.

“He was quite outstanding,” says Tyrrell. “He was clearly the best German driver since before the war. He was incredibly brave and so fast. He was also very, very easy to like. It was hard to be cross with him and he probably got away with things he otherwise wouldn’t have because of that.”

There was a wet test at Zandvoort that year. Bellof was driving the first turbo Tyrrell, not a good car. Gerhard Berger, who previously considered himself untouchable in such conditions, was out in his Arrows-BMW. What transpired compelled Berger to talk to Stappert

“Gerhard told me this Tyrrell just keeps on closing, closing and he can’t believe it, because he’s driving absolutely at his limit. Eventually it passes him and pulls away. Gerhard said he was caught by a mixture of fear and respect because he’d seen someone for the first time do something he for sure could not.” That respect is still there today. Ask Berger about Bellof and he replies: “He was one of the best, I mean one of the very best. I don’t say that lightly. He was a future champion for sure, perhaps many times. He was going to be the big rival of Senna, I think. They don’t come along very often like him. He was very special.”

“Although they were not all that close,” says Stappert, “I think Stefan and Gerhard would have become good friends. They spoke the same language and they both had only shit in their heads! There was no joke too bad to tell or do.”

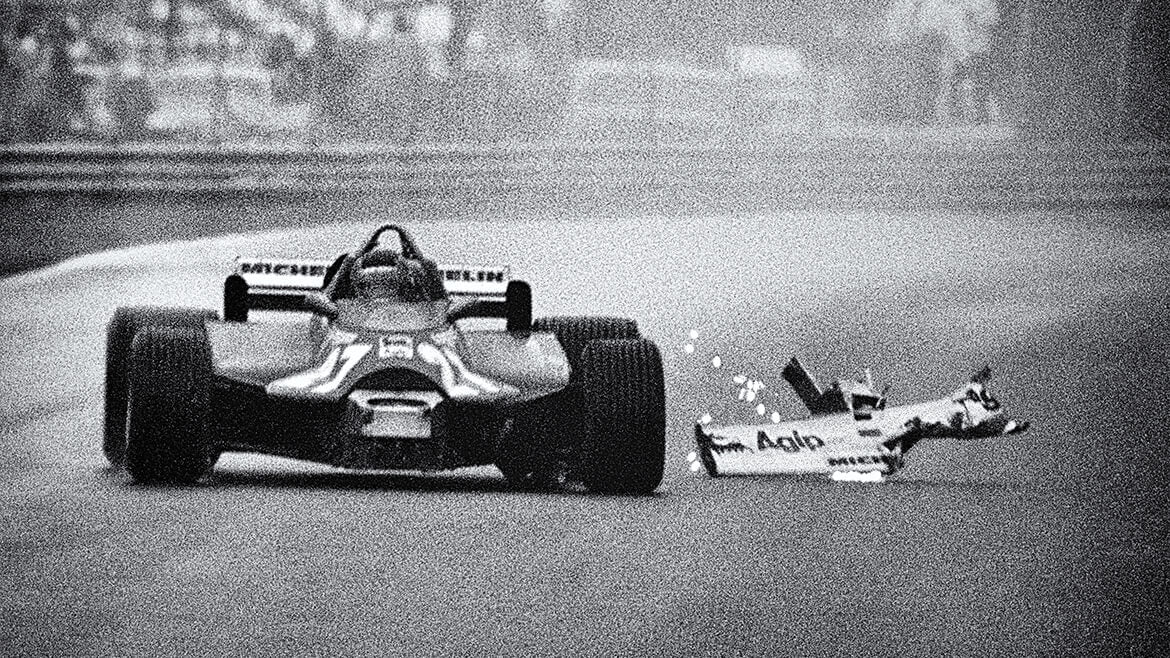

No move too difficult to try. At the 1985 Spa 1000 Kilometres, Bellof’s Brun Porsche had been hassling Ickx’s works car for several laps. Then, fatally, he tried to go round the outside at Eau Rouge. No one ever passes there. But when had such a notion ever stopped Bellof?

“I’m sure at that moment he was laughing,” says Braun. “He must make a show, it’s the home ground for Ickx in the factory car. Let’s pass him in the biggest corner, in front of everyone, round the outside. That was Stefan.”

So it was. “Racing’s not about backing off,” says Bell. “But it is about having full control of yourself and your talent. If only someone had been able to instil that in him.” If only.

‘They don’t come along very often like him. He was very special’ – Gerhard Berger

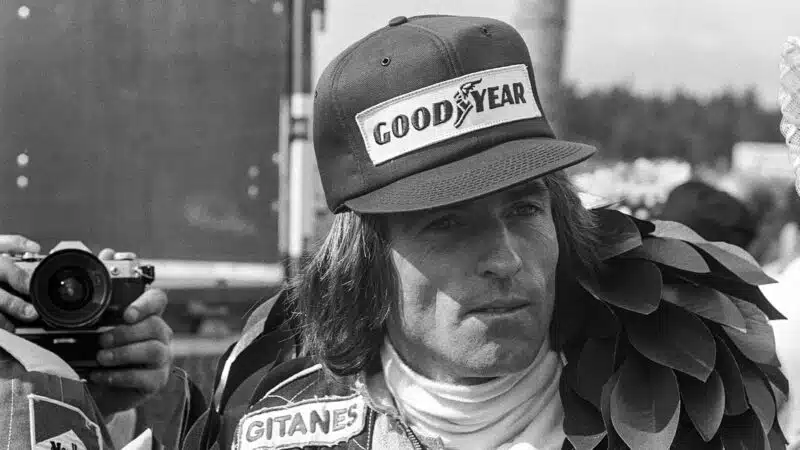

Ferrari had minor success as driver

Ferrari had minor success as driver

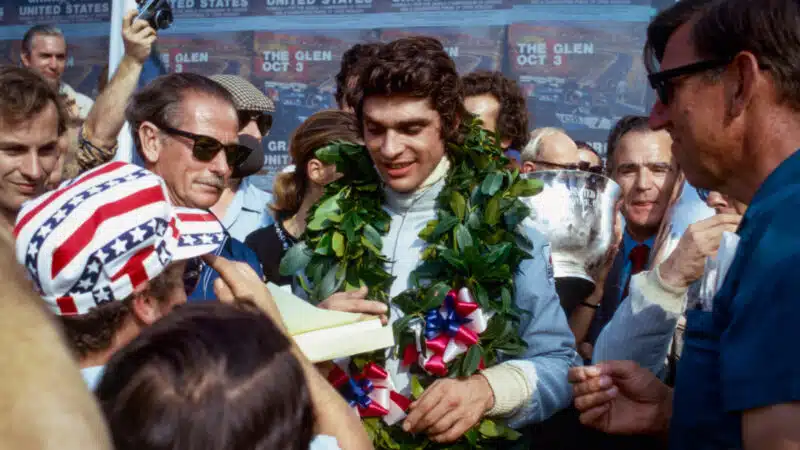

On the last day of his life at Watkins Glen, Cevert was once again among the pacesetters in his Tyrrell

On the last day of his life at Watkins Glen, Cevert was once again among the pacesetters in his Tyrrell